09 Jun In the Studio: John Austin Hanna

You won’t find a computer in acclaimed Fredericksburg artist John Austin Hanna’s studio — but that’s because it’s the offline world that drives his passion for art.

The native Texan started drawing at age 5, and it’s a passion that hasn’t waned since. Hanna says art just came naturally for him — in an age where there wasn’t formal art school training, or the judgment of others. It was more the drive to create art for art’s sake, without worry as to how it happened.

“Everyone likes to have a pat on the back,” he says. “When you do something that other people appreciate … maybe that’s part of it. It was something I just stumbled on. Other kids were playing games; I just enjoyed getting paper and pencil and drawing.”

That pure enjoyment for creating art propelled Hanna from a successful career as a commercial illustrator for both New York and Dallas advertising agencies to a painting career that has lasted more than 30 years. And much of that success is deeply rooted in Fredericksburg — the sleepy Hill Country enclave outside of Austin where Hanna and his wife, Sherry, have made their home since 1978.

The journey that drew the Hannas to Fredericksburg started while they were still living in Dallas. They were planning a trip to the scenic Big Bend area in West Texas and asked friends about must-visit places along the way.

“We were told that Fredericksburg was an interesting stop, so we went,” recalls Hanna. “We fell in love with the place and just couldn’t get it out of our system.”

The move was pivotal in other ways, too. In fact, Hanna calls the decision to relocate to Fredericksburg the turning point for when he decided to focus on painting and not commercial illustration.

He’d painted off and on his whole life — selling his first painting to his seventh-grade teacher — but it was never his sole focus until he moved to Fredericksburg.

“I didn’t go to a ‘real’ art school — there were a few around, but not many — and I didn’t have the direction to do it anyway,” he says. “I liked driving in the country and seeing things I wanted to paint in Fredericksburg. The city never seemed to work for me in that way.”

Hanna’s early studios were multiple iterations of a search for the right creative space. He owned several small houses in town and would often use them to paint when they weren’t rented out. And then there were the two 16-by-16 rooms at Dooley’s Five & Dime back in the mid-1980s.

“It cost me $25 a month, and they were pretty ratty back then. And hot,” he says with a laugh. “I had to quit by noon every day because of the heat. But as an artist, I guess you have to suffer.”

Hanna’s space today is tucked away on the back lot of the property behind his house. A hermitage of sorts, he designed it himself with the vision that it could be an outbuilding with the look and feel of a studio space, and a dedication to the history and architecture that defines Fredericksburg.

“I didn’t want to do something out of place for this area,” he says. “I had a chance to buy a building and move it here, but couldn’t because of building code restrictions, so I designed my own.”

It’s clear Hanna adores his creative space — he calls it his home away from home and found himself spending a lot of time there over the years, even when he wasn’t painting. But he’s not sure that the space shapes what he does as an artist.

“If you have the inspiration to do something, it doesn’t matter where you are,” he explains. “You can do anything. A space just makes it convenient and comfortable.”

What has influenced his art, however, is the town of Fredericksburg itself. Main Street is its epicenter — a long, meandering block of antique stores, art galleries, boutiques, old-fashioned soda shops, pottery shops and jewelry studios — and it’s also where Hanna’s house and studio are located. It’s the kind of place that elicits a fierce passion in residents to protect and preserve its quaint German-influenced history, and Hanna is no exception.

“Things have changed an awful lot here — I started painting local places 30 years ago, and those places have changed, or are gone,” he says. “Now I want to do more farms and preserve what’s there.”

Joe Sylvan, owner of The Sylvan Gallery in Charleston, South Carolina, which has represented Hanna’s work for the last several years, calls Fredericksburg a very artist-friendly town that spawns creativity. “It’s one of those tranquil places with all the benefits of a small town,” he says. “Most artists want to settle in a place where they can work on their craft, and Fredericksburg is like that.”

The town has offered plenty of fodder for Hanna’s art over the years, including interesting landscapes. Fredericksburg has a number of family farms and generational land that has been around for years, passed down from one family member to the next. But as owners are getting older and dying off, the children often don’t want the property and are selling for a small fortune to new owners who want to tear down and upgrade.

“It’s nice, but it’s not worth painting,” says Hanna. “There’s no humanity, no character left to them. The lady I buy eggs from once a week, her place hasn’t changed. But those places are getting few and far between.”

Hanna does see himself as a bit of a historian for Fredericksburg, preserving its history, people, culture and sense of place through his art — and that’s what makes his work so appealing to galleries.

“He has a strong Western background, but his paintings go from the coasts to the mountains,” says Sylvan. “People respond to his work because they’ve been there, too.”

“I can see the story of the generations that have grown up there, living on a farm — I can see that,” says Hanna. “There’s a story behind everything. The key is in finding it.”

- “House on Austin Street” | Oil | 12 x 16 inches

- Hanna’s palette awaits his brush.

- Hanna’s studio is nestled in the trees behind his Fredericksburg home. A well-traveled footpath suggests how often the artist makes his way to the studio.

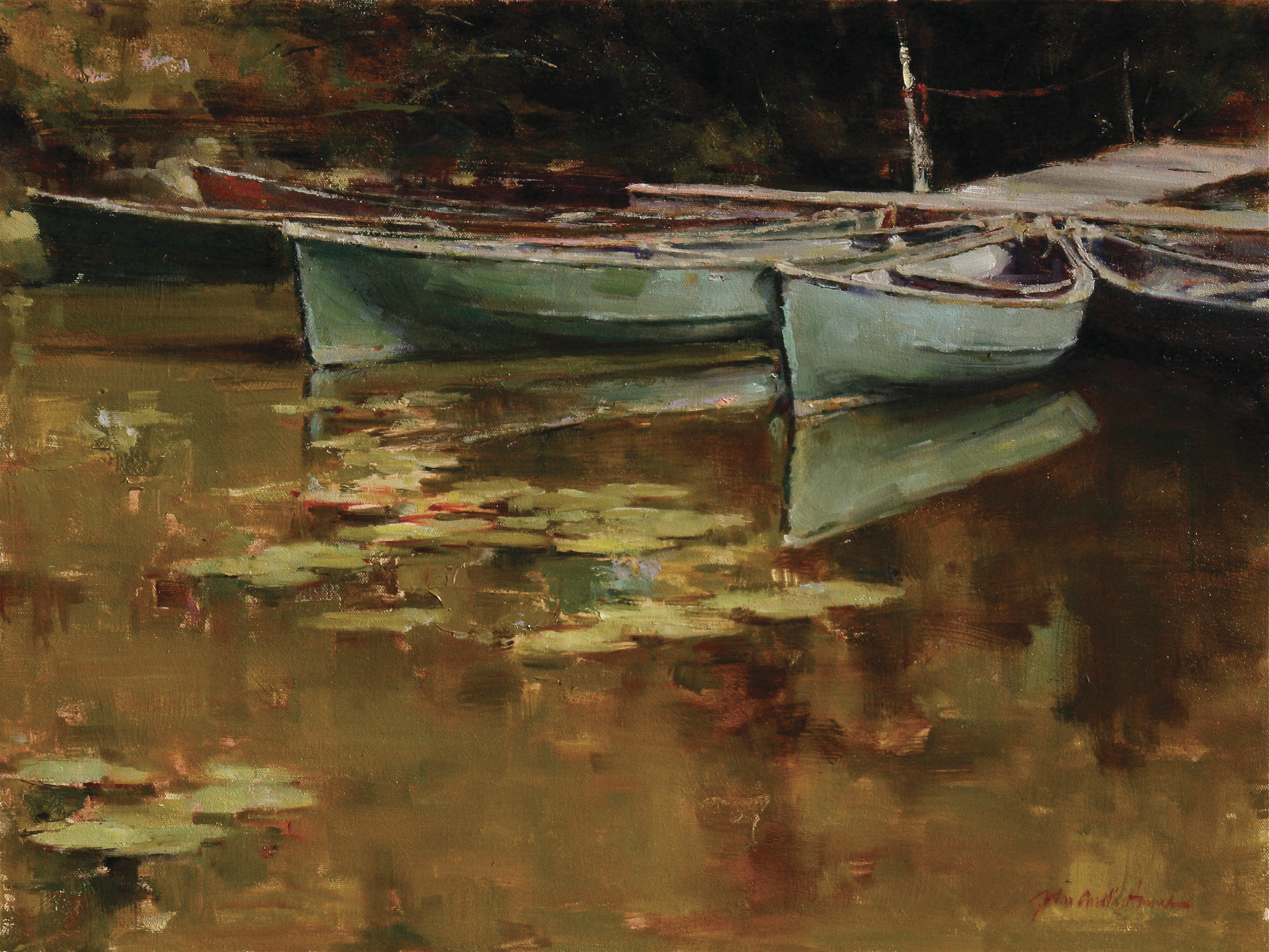

- “Season’s End” | Oil | 18 x 24 inches

- “Ridin’ High” | Oil | 28 x 22 inches

- Hanna’s work space is part library, part gallery, and chock full of his painting tools.

- “Garden Spirit” | Oil | 24 x 18 inches

No Comments