30 May Perspective: Gennie DeWeese [1921-2007]

It is nearly impossible to tell the story of contemporary Western art without understanding the work and influence of Gennie DeWeese. Along with husband, painter Bob DeWeese, Gennie’s presence injected the Western art scene with an infectious energy, bringing a Western take on Modernism and non-objective Expressionism to far-flung regions of the country during the 1940s and ’50s. A true pioneer, Gennie DeWeese was also matriarchal in every sense of the word; caring for, overseeing and — very much like a mother osprey — encouraging three generations of contemporary artists to fly on their own.

Elizabeth Guheen, director and chief curator at the Bair Family Museum, U Cross Foundation president for 16 years and a previous senior curator at the Yellowstone Art Museum, sees DeWeese as an important American artist in the West. “Just the fact that she drew all her subject matter from her family and her surroundings with materials she had on hand makes her an important artist,” she says. “She wasn’t concerned with making something monumental. She was concerned with translating the importance of immediacy. The rough hewn of ‘I see it and I’m putting it down.’”

Commenting on what made DeWeese’s work uniquely Western, Guheen explained, “All of her subjects were drawn from her own life using indigenous materials, especially the cattle markers. … She was very spontaneous and very connected to her environment.”

But there were universal elements in her work and process, too, that elevated DeWeese above clearly defined genres. “Gennie DeWeese was a role model for students and younger artists,” Guheen said. “I think it’s important to see serious career artists not getting bogged down in a certain way to approach art. Her ethic was work. Make art no matter what else you do. She sent that message to all the artists and students she came into contact with.”

Born in 1921, Gennie Adams and her family moved from Indianapolis to Grosse Pointe, Michigan, then to Columbus, Ohio. In 1938 she enrolled in Ohio State University, where she met Bob DeWeese. During WWII, she went into occupational therapy, enrolling in a training course offered to artists by the Army. She worked with head- and nerve-injured soldiers in Battle Creek, Michigan. When Bob returned home from the war the couple married, and in 1949 they moved to Bozeman, Montana, where Bob taught art at the university.

The DeWeeses brought new ideas of Modernism to Montana, long known as the land of Charlie Russell. Together, they opened the doors of contemporary art, not only to Bob’s students, but to a small group of intellectuals and artists whose work extended beyond the boundaries of the ivory tower. Under Gennie’s tutelage — between plates of food, trays of beer (as depicted in Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance) and late night conversations — creativity abounded.

“There were only a few other people in Montana at that time who experienced art in those terms, thus becoming a close network and community that evolved into lifetime friendships,” said Tina DeWeese, daughter and archivist for her parents’ work. “But they weren’t intimidated by the isolation. They were excited and charged up with these ideas — ideas from their college days infused with the energies generating from the wave of Abstract Expressionism exploding through the East Coast.” The community that emerged became an ongoing, organic evolution of various generations of artists and included such luminaries as Rudy Autio, Bill Stockton and Peter Voulkos.

The DeWeeses had five children between 1947 and 1963 (Cathie, Jan, Gretchen, Tina and Josh — all of whom grew up to be artists/musicians/social activists), and Gennie painted continuously while keeping her family the central focus of their lives. Beginning in the mid-1950s, she exhibited her work in shows across the West, from Montana and South Dakota to Seattle and San Francisco.

Primarily an oil painter, DeWeese also worked in cattle markers, paint sticks and oil sticks, as well as drawing and woodcut printmaking, monoprints and lithographs. Over her 86 years, she produced decades and decades of art in at least a half-dozen general periods of work. Beginning with drawings and paintings of her children, Gennie’s work evolved into more abstract studies in the 1950s and ’60s. The family’s collection of hundreds of drawings traces the roots of this evolving form which became her signature mark, and is apparent even in her later, and now familiar, landscapes.

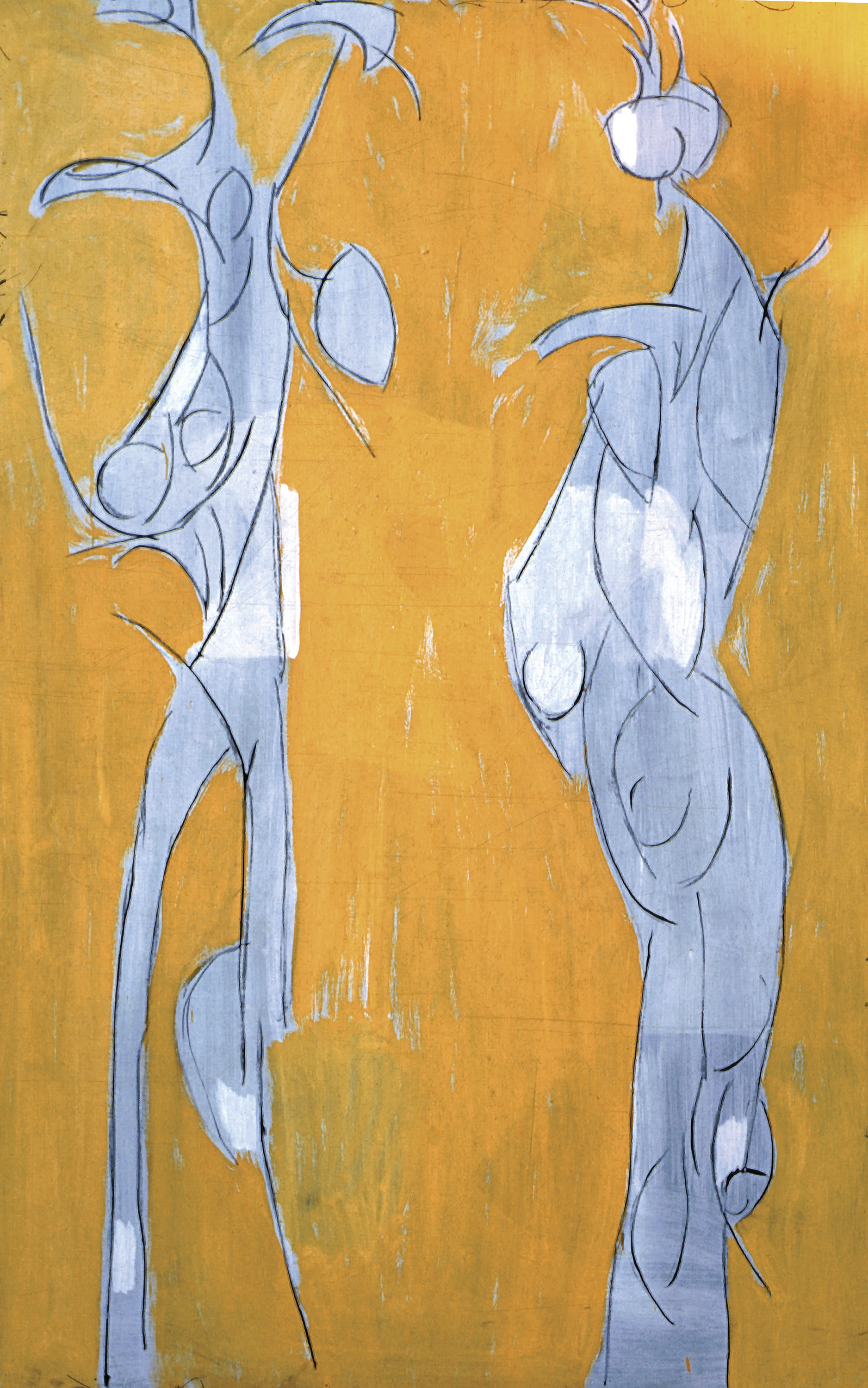

With her gestural studies of form derived from nature, DeWeese then came to a period of very loose amorphous Expressionism. She continued to evolve, working with line and shape more organically.

“From there she moved into what we’ve been calling her Totem Period,” Tina said, pointing to several paintings where the forms are somewhat stacked, both vertically and horizontally. “In her mythic-themed work you can see a lot of the same elements, but she started to work with the ideas of myth and mythic figures like Medea, Isis, Cassandra and Pieta.”

After that her work veered more toward landscapes, which coincided with the family’s move from town to the mountains in the late 1960s. “People loved her landscapes and it was a very prolific period for her,” Tina said, adding, “She was prolific in every decade of her life.”

By the mid-1980s, DeWeese began to convert from traditional oil and brush work canvases (although on non-traditional gessoed Masonite) to the scrolls for which she is most widely known today.

Terry Karson, former curator of the Yellowstone Art Center (now the Yellowstone Art Museum) in Billings, Montana, curator of Gennie and Bob DeWeese’s retrospective shows, and perhaps the top scholar of Gennie DeWeese’s work, has chronicled her work throughout the years.

“As her work sold she upgraded her materials, which brought more collectors to her paintings,” Karson said. “As far as pure goes, Gennie was a master painter. She had the master’s touch. After Bob died she started doing all these amazing paintings. Her kids were gone and she started to really come into her own. I would stand Gennie up shoulder to shoulder with any painter in the world during those last 20 years of her life.”

Beginning in the early 1990s, her work received national recognition, and by 1992 she was being collected widely. In 1995 DeWeese garnered the Montana Governor’s Award and an honorary doctorate degree from Montana State University; in 1996 she had her first major retrospective at the Art Museum of Missoula.

In an artist statement DeWeese authored in the 1990s, she said that her non-objective work opened up avenues of visual awareness in the landscapes she returned to when she moved to the mountains and was confronted daily with “visual feasts.”

“What became important was to try to transmit that impact,” she wrote. “Cattle markers, paint sticks and recently oil bars became my means of personal expression that were close to oil painting yet contained a quality that felt more comfortable. I don’t know why. I love color but feel it is the icing on the cake. Structure is first.”

In that same statement, she commented on her transition to scrolls.

“I became intrigued with the idea of doing scrolls rather than framed paintings both from the practical standpoint of ease of storage but more importantly to introduce the Japanese tradition of ease in changing displays according to the seasons, moods or whims,” she wrote. “One need not have the same thing in the same spot year in and year out. It allows more personal contact and decisions from the observer.”

The youngest of Bob and Gennie’s children, Josh DeWeese, an internationally recognized ceramic artist and former director of the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts, appreciates his mother’s work not just as a son but as an artist and a teacher.

“She developed a particular way of capturing the quality of color and light in the landscape, and the sense of generosity, maybe with the bold and direct nature of how she worked,” he said. “I think it is very honest work; she painted what she saw. She was devoted to what she believed were basic principles of visual organization, and any image had potential. It was how one dealt with the balance and composition of the painting that made it successful or not.”

One look at her large, rich paintings and her generosity of spirit is apparent, but it was also DeWeese’s actions, her unwavering support of her fellow artists, young and old alike, that endeared her to so many. The DeWeese household bustled with inspiration and art.

“Gennie was a masterful social nurturer, a great cook and she had some great dinner parties,” Tina DeWeese said. “She was always a great supporter of other artists. All of my mother’s calendars were centered on art openings.”

Even if it meant traveling hundreds of miles.

“She spent a lot of energy by being present,” Tina said.

Which didn’t take away from her being a prolific artist. DeWeese’s studio was always full to brimming with paintings, drawings and prints.

Josh remembered what it like being a kid in such a creative setting.

“Growing up in that environment was perfectly normal, or at least I thought it was, which it wasn’t, of course, and that’s the point,” he said. “It was very special, but no one made a big deal of it. We were supported in whatever we did. We were held accountable for our actions. We were taught to be considerate of our fellow human beings, whoever they were. Looking back on it, it was endlessly entertaining and stimulating with the constant interaction of friends and visitors who were always welcome in the home. I feel incredibly fortunate.”

Josh added that his mother was a true champion for young artists, “particularly young women artists that she was genuinely interested in and supportive of her whole life,” he explained.

What is apparent in DeWeese’s work, and perhaps best defines her impact on Western painters, is her ability to see the world — whether landscapes, interiors or figures — as it is revealed to the painter; to naturally focus on a single element without seeming to leave out the context. Like a photographer choosing the perfect shot, DeWeese composed what she saw honestly and without compromise.

From the back streets and alleys of New York City’s underground art scene to Montana’s rugged landscapes, Michele Corriel writes about art in its many forms. She is recognized for using her background in poetry to describe the creative process, garnering numerous awards for her work. Her second book Weird Rocks, will be out this fall and she is currently working on her third.

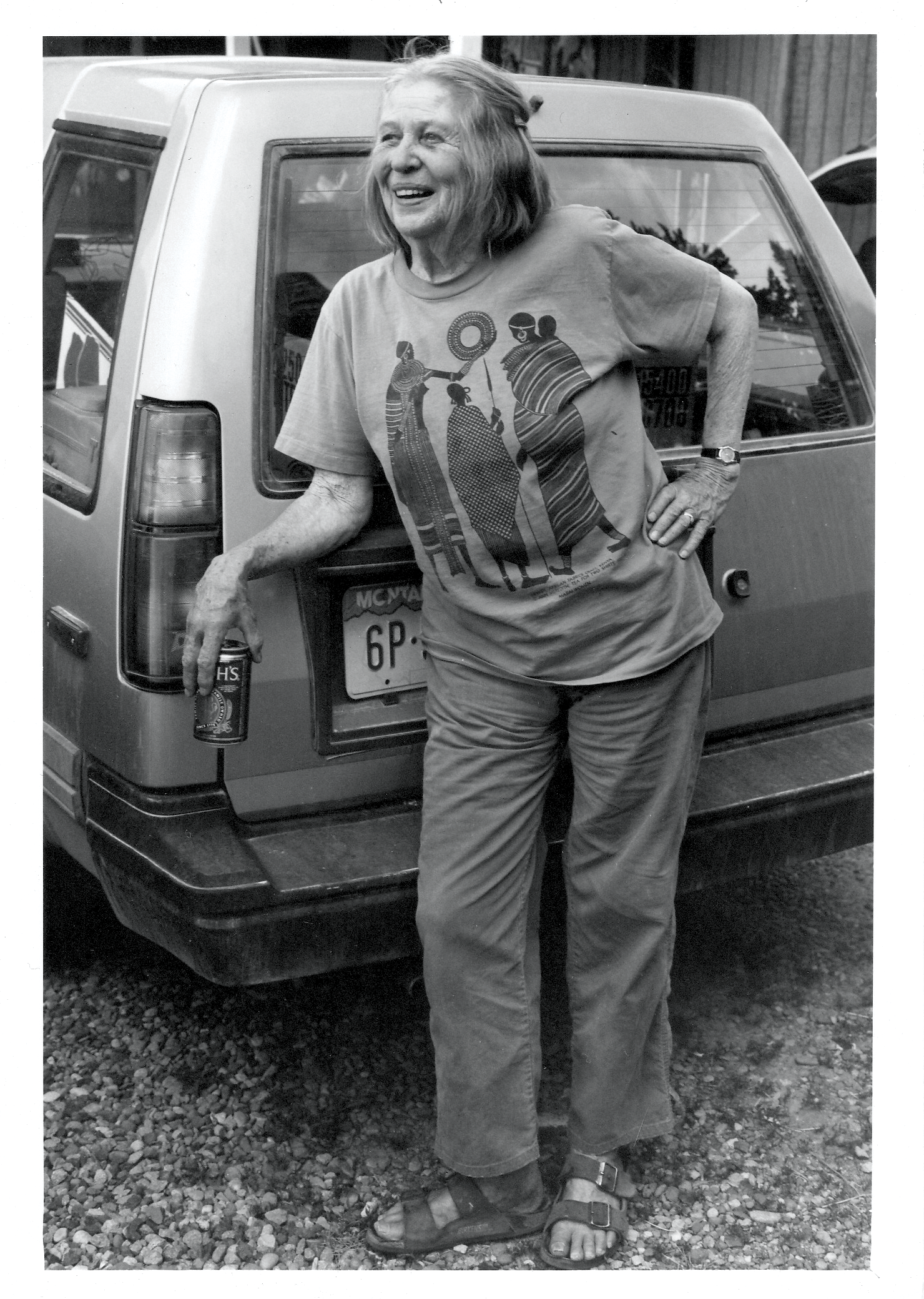

- Painter Gennie DeWeese

- “Tina” | Oil on masonite | 28 x 21 inches | 1958 | Collection of Tina DeWeese

- “Pepper in the Doorway” | Woodcut print with watercolor wash | 30 x 20 inches | 1999

- “Marigolds and Nasturtiams” | Oil bar on paper | 37 x 37 inches | 1989 | Collection of Mira Shimbukuro

- “Two Figures” | Oil on masonite | 48 x 72 inches | 1960

No Comments