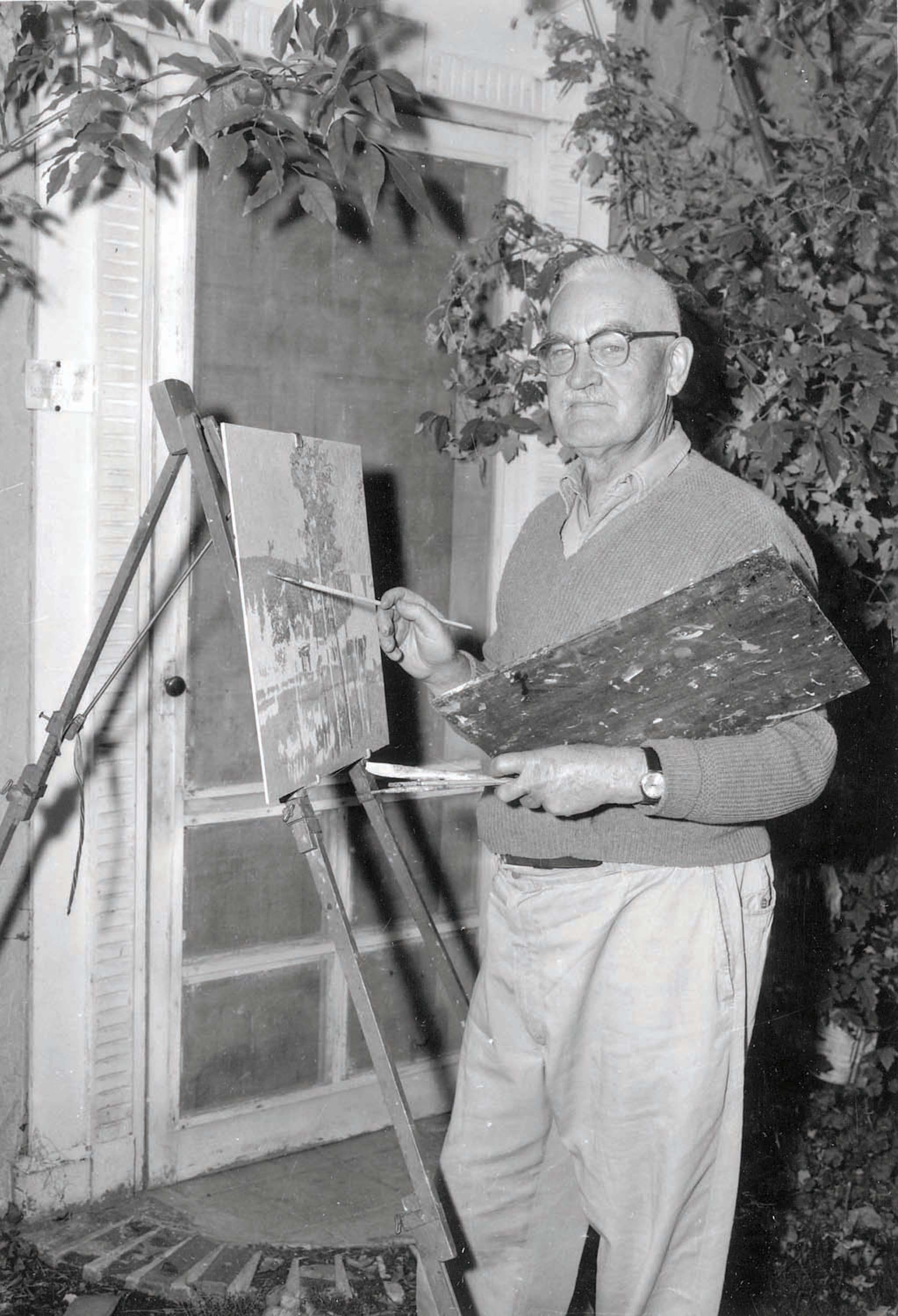

01 Feb Perspective: LeConte Stewart [1891-1990]

At first glance, there isn’t much to see. A bucolic setting of gentle shrubbed mountains and neatly plowed farmland punctuated by a simple house, a barn and a perimeter of poplar trees. Typical northern Utah land — a mix of stunning natural beauty and the signs of those who would earn a living from the earth.

But somewhere in the distance, from the vantage point of a lonely road or a quiet pasture, someone is watching.

With medium-sized canvases and the decisive work of his brush, LeConte Stewart [1891–1990] stayed in this vantage point, painting everything he saw — the colors, the light, the land — quickly. Within an hour and a half, when the earth’s rotation changed the angle of sunlight, he had completed his work. And he would return again and again until he deemed the painting complete. Or he would return to the same spot months later, when the seasons had altered the landscape and his eyes saw something very different than what he had painted.

LeConte Stewart was a painter on every level. He often told friends and family that he would rather paint than eat. And seemingly he did, sketching and painting every single day of his life. At the time of his death, his working legacy included more than 7,500 pieces as a painter, beloved instructor and chair of the Fine Arts department at the University of Utah. Art experts cite him as gifted on many fronts — etching, drawing, lithography — he certainly could do it all. But it was his skill and persistence as a painter that modern collectors and fans of Stewart recognize and are bringing to light in the realm of Western art.

In the autumn of 2011, parallel exhibits in Salt Lake City showcased Stewart’s work. To commemorate the 120th anniversary of the artist’s birth, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts staged LeConte Stewart: Depression Era Art and the LDS Church History Museum offered LeConte Stewart: The Soul of Rural Utah. Both covered Stewart’s work from the 1920s to the 1950s.

Both Dr. Donna Poulton, associate curator of art of Utah and the West at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, and Robert Davis, curator of the Church History Museum are admirers of LeConte Stewart. Poulton has written several books about Utah art, which invariably include Stewart. Davis’ family even collects some of Stewart’s art. So when the two pooled their contacts and community resources, they were able to aggregate a stunning body of work.

When Dr. Poulton spoke with Stewart’s friends and family, as well as collectors, and saw the sheer span of his work, she was struck. Among boxes were notes and guides he created as an art instructor at the University of Utah, sketches, drawings, compositions, color studies, even recipes for paints. There was a remarkable body of art showing exactly how Stewart worked. Then, of course, there were the paintings in the collections of Utah art enthusiasts.

“There were too many works for just one venue,” Poulton says. “It was clear that a partnership with the Church History Museum would be a good way to show Stewart’s art.” The Church History Museum focused on Stewart’s prolific landscapes while the Utah Museum of Fine Arts focused on his body of work during the Depression. Each paid homage to Stewart’s impressive technical detail, skill and perspective in the landscape genre.

Poulton cites the philosophies of some of Stewart’s peers, including gentleman farmer and poet Wendell Berry, as well as contemporary Western writer Wallace Stegner. “These people believed that if you don’t know where you are, then you don’t know who you are.”

“Stewart’s training brought him face to face with the question of ‘what is landscape?’” Davis explains. “And it simply wasn’t a personal expression, but rather a camaraderie among a community.”

This “knowledge of place” was a cornerstone of Stewart’s work and it was honed, oddly enough, in workshops and programs back East. After scrimping and saving to train under John F. Carlson and Walter Goltz as well as the Art Students League, Stewart discovered, stroke by stroke, firsthand what it meant when Carlson told him “a picture is a work of art not because it is ‘modern,’ not because it is ‘ancient,’ but because it is a sincere expression of human feeling.’”

And for a young Stewart, a timid but driven man, that expression was most likely a vital one. His childhood was marred by the tragic and traumatic passing of his siblings and his mother. When his father, an attorney, passed away, Stewart, a devout Mormon, was left in the care of other lawyerly uncles.

He was used to being alone, a trait that served him well as he trekked across northern Utah landscapes and lonely roads for hours in pursuit of his art. When not painting, Stewart was in the comfort and company of his beloved wife and most ardent supporter, Zipporah, and their children.

Stewart’s caretakers wanted him to follow the family trade with a respectable career in law. But the artist knew early on that his future held something different and despite his introspective, gentle mien, he had a steely, single-minded resolve to become a painter.

His natural skill and mentoring back East produced in Stewart a painting style that’s deceptively straightforward. Stewart, didn’t absorb fads the way other artists did. His Realism was a steady and reliable constant throughout an era known for Modern art. Stark, bleak and clear, Stewart painted seemingly innocuous scenes.

However, upon closer inspection, it’s obvious that Stewart’s work exhibits technical capability and an emotional depth that isn’t brash and showy. In an understated way, his paintings are an elegant display of the natural landscape and man’s relationship with it.

Both Poulton and Davis point to his excellent compositions: The way a country road or a wash bisects the canvas and the mountainous fall backdrop, as in Stewart’s November Hills; or even more prevalent in his pieces of human settlement, the use of lines from telephone poles and lines to railroad tracks. Stewart uses the man-made lines of buildings to scale and frame a focal point.

Smith’s House exemplifies this skill. Poulton and Davis recovered various studies of the house, enabling museum visitors to see the evolution of a painting. Eventually, the final work features a subtle but intricate play of light and a meticulous use of color, all simply and profoundly bordered by the trappings of civilization.

Both Poulton and Davis agree that Stewart is arguably Utah’s most important landscape painter. And his work would classify him as a “Regionalist” long before the term came about. But that was Utah in the 1920s — the rural communities with their soaring unemployment and foreclosure rates felt the heavy hand of the Depression long before many other places did.

Slowly, as Stewart observed and painted, communities grew sparse. Homes were left abandoned. His landscapes were by default turning into Social Realist pieces. Not only was Western landscape master Maynard Dixon a contemporary to Stewart, but with bleak pieces such as The Victorian, North Salt Lake City, Stewart was thrust into the company of artists including Edward Hopper and Dorothea Lange. By simply observing, painting and doing the only thing he felt compelled to do, Stewart added his expression to the social commentary.

Among his most striking works is Private Car. Anonymous faces of work-seekers under a late afternoon sun are made more poignant by the figure of a defiant man, standing in the railway car. “It was painted on the Ogden Railway,” Poulton says. “But really, it could be anywhere in Depression-era America.” Stewart painted the piece as an ironic contrast to the daily transport of the Ogden station manager, who was chauffeured to and from work in a limousine.

For Davis, pieces like this emphasize Stewart’s skill. “Many artists will use the term ‘painter of light,’” he explains. “But Stewart was truly a master of light and of color.”

His mastery also included the subtle adaption of Impressionist techniques in his Realist paintings. His seamlessness allowed for the use of several different techniques on one canvas. Additionally, Stewart’s frugality often contributed to the display of his impressive range of skills since his canvases were frequently painted on both sides.

As the nation entered World War II and pulled itself out of the Depression, Stewart continued to pursue his art. He painted the ever-changing landscape with the growth of agriculture, the growth of cities and towns. He chronicled the decline of the farmhouse and disappearance of barns, the increasing presence of suburbia and cookie-cutter housing.

The Smiths’, the Joneses’, and the Browns’ epitomizes this perspective. Stewart captured one frame in the exponentially growing West. And for this humble man, it wasn’t a direction that suited him. A row of planned housing that looked and felt exactly the same, side-by-side, again framed with more telephone poles. A resident pops into the field to see what Stewart is doing.

Later, he would tell family members to forge their own path. To not be swayed or compelled to do, say or act as anyone else was thinking. And to those family members and friends, he lived as an example, quietly painting his way, every day, in a landscape that was forever changing.

- LeConte Stewart

- “Smith’s House” | 1937 | 30 x 36 inches | Courtesy the UMFA

- “The Smiths’, the Jones’, and the Browns’” | c. 1936 | 30 x 48 inches | Courtesy of Springville Museum of Art

- “Private Car” | 1937 | 30 x 48 inches | Courtesy the LDS Church History Museum

No Comments