16 May Perspective: Nicolai Fechin [1881–1955]

In 1895 in the Russian town of Kazan, a trading port and cultural crossroads on the wide Volga River, 13-year-old Nicolai Ivanovich Fechin stood at a crossroads in life. His father was a masterful artisan skilled in woodworking, architecture, painting, gilding and cabinetry, but less adept at business, and the family had to give up their home. Nicolai’s brother and mother were moving to another town to live with the boys’ grandmother, while their father would travel from village to village as an itinerant craftsman. Young Nicolai could have gone with either parent. Instead, he chose a third, and fortuitous, path.

That same year, a graduate of the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg had opened a branch school in Kazan. It offered painting, sculpture, architecture and general education instruction to youth from families of all means, not only the wealthy. Nicolai, having spent his boyhood happily engaged in drawing and woodcarving in his father’s workshop, decided to stay in Kazan and attend the school. His father proudly approved. With a classmate, the boy moved into a disused house and subsisted on little more than bread, honey and tea while he attended the six-year school.

“It was kind of a miraculous piece of providence. Without that school, Fechin would have needed either a patron or money to hire a master to teach him art, which of course his family didn’t have,” says Susan Fisher, director of the Taos Art Museum in New Mexico, which holds a collection of Fechin paintings, most on long-term loan from private collections. The Kazan Art School was the first in a series of decisive steps that eventually led Fechin to an acclaimed international art career, the second half of which took place in the American West.

The door to Fisher’s adobe-walled office opens into the large, high-ceilinged room that was Fechin’s studio for most of the six years — 1927 to 1933 — that he, his wife, Alexandra, and their daughter, Eya, lived in Taos. Filled with light from an enormous, many-paned north window and slanted skylight, it is where the painter enjoyed what were probably his most prolific years. Here, he painted landscapes, interiors, still lifes and countless portraits, the genre for which he is most known and admired. Among his commissioned portrait subjects were Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, General Douglas MacArthur and American actress Lillian Gish.

Across an outdoor walkway from Fechin’s studio sits the two-story white adobe house where he and his family lived, which is now the Taos Art Museum at Fechin House. Originally a two-room, Pueblo-style adobe built in 1915, Fechin expanded it to include a kitchen, study for Eya, upstairs sunroom and bedroom, and a large piano salon, all designed by the artist and built with help from locals. Once the additions were complete, Fechin spent all his daylight hours in his studio, painting by natural light. When the sun dipped low, he picked up his woodworking tools.

All of the home’s furniture was designed and built by Fechin and adorned in the Russian tradition of elaborately carved wood. He also executed intricate carvings on wooden radiator covers, posts, banisters and doors. His approach included the Russian farmhouse aesthetic, but went well beyond it, incorporating elements of Moorish, Spanish Colonial, Native American and Art Deco motifs. “The thing he did that was so rare was to make a synthesis,” Fisher says. “He married design elements into a recognizable signature style.”

“When my grandfather got to Taos, he felt very at home,” relates Fechin’s granddaughter, Nicaela Donner, explaining that the mountains reminded him of parts of Russia; the native language of the Taos Pueblo sounded a little like Russian to him; and the Spanish and Pueblo cultures fed his fascination with “people of the land,” as he called them, just as he’d been intrigued by the Siberian and Tatar people in Russia. As Eya wrote of her father in the 1982 book Fechin: The Builder, “There was a deep satisfaction in bringing this much of his motherland to a foreign but seemingly familiar corner of the world. Indeed, he was compelled, driven to reproduce such an environment within which his soul felt at home and his painting flourished.”

Donner was born two months after her grandfather died and grew up hearing stories about his life. She tells of an incident in Fechin’s boyhood that offers a clue to his intensely creative nature. When he was 3 years old, he contracted meningitis and fell into a coma. Believing he would not live, and as a last resort, his parents sent for the elders of the local Russian Orthodox Church to bring a holy icon to his bed and pray. After the icon was passed over the boy’s body, he awoke from the coma. He recovered completely. Although Fechin was not particularly religious, the experience made a profound impression on him. “He felt he had things to accomplish,” Donner says.

Fechin’s performance at the Kazan Art School qualified him for entry into the Imperial Academy. There, he studied with Ilya Repin, the most renowned painter in Russia at the time. Upon graduation in 1908, Fechin was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome, a traveling scholarship that allowed him to visit art museums and galleries in the art capitols of Europe. He returned to Kazan in 1909 and began teaching at the Kazan Art School. In 1910, he received a gold medal for painting at the annual International Exhibition in Munich and was invited to show at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

In Kazan, Fechin married Alexandra Belkovitch, the Kazan Art School director’s daughter, and Eya was born in 1914. As an instructor at the school for 10 years, Fechin was beloved by his students, Fisher says. “He had neoclassical training but was also self-taught in his father’s workshop,” says Fisher. “The neoclassical canon was not his choice, and he respected his students’ choices.” Fisher believes the artist would have remained in Russia were it not for the responsibility of a child during the economic and social upheaval in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution. Both his parents died of typhoid fever and food shortages became critical. Fechin’s association with collectors in Europe and America made it possible for him to immigrate to New York City with his family in 1923.

In New York, Fechin exhibited, gained commissions, won awards and began teaching at the New York Academy of Art. But he was not made for urban life. A tuberculosis diagnosis reinforced his need to leave the city, and a friend, Scottish-American painter John Young-Hunter, suggested he visit Taos. In 1927, the family made the long journey west. They lived briefly in the Taos compound of socialite and art patron Mabel Dodge Luhan and then bought 10 acres adjoining her property, with an adobe house and outbuilding. Fechin immediately cut and raised the outbuilding’s roof, installed a massive skylight, set up his studio and then began work on the house.

While the Imperial Academy had favored enormous canvases and often-muted hues, in New Mexico Fechin’s paintings grew smaller, more impressionistic and were filled with color and light. “In Taos his brushstrokes became looser — still thoughtful and elegantly controlled, but more diffused over the canvas. In places, there’s an almost calligraphic feeling about the brushstrokes, and you see very broad strokes of separate colors not mixed together. He would not have done that in Russia,” Fisher says. “It’s an astute combination of abstraction and representation.”

Even as Fechin’s style evolved, his portraits continued to convey a powerful and often tender sense of his subjects, especially those to whom he was closest. He created numerous portraits of Alexandra and Eya, and was able to paint his father from memory for years after his father’s death. Then, in 1933, six years after moving to Taos, Alexandra divorced Nicolai, an experience that shattered him. As Donner reflects, “I came to the conclusion that he and Alexandra divorced because the marriage became difficult for two people creating a new home and trying to live their lives with individual independence intact.”

Following the divorce, Fechin and Eya moved briefly to New York and then to Southern California, while Alexandra kept the house and remained in Taos. In the next few years, Fechin made painting trips to Mexico, Bali and Japan, drawn to the color and people of those places. He and Eya settled in Santa Monica, California, where he painted and taught until his death in October 1955. In the 1970s, Eya returned to New Mexico and carried out her longtime mission of preserving the Fechin house and having it become a museum. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

Opening Fechin’s former home to the world was a fitting tribute to the art and craftsmanship of someone who opened himself to the world artistically while also remaining a quiet, almost solitary man whose language was painting and who survived wrenching separation from his homeland and family, Fisher says. “He had a great worldliness and level of achievement, but on the other hand his world was also intimate and small. I think of him as a snail who carries his world on his back — his world was his art.”

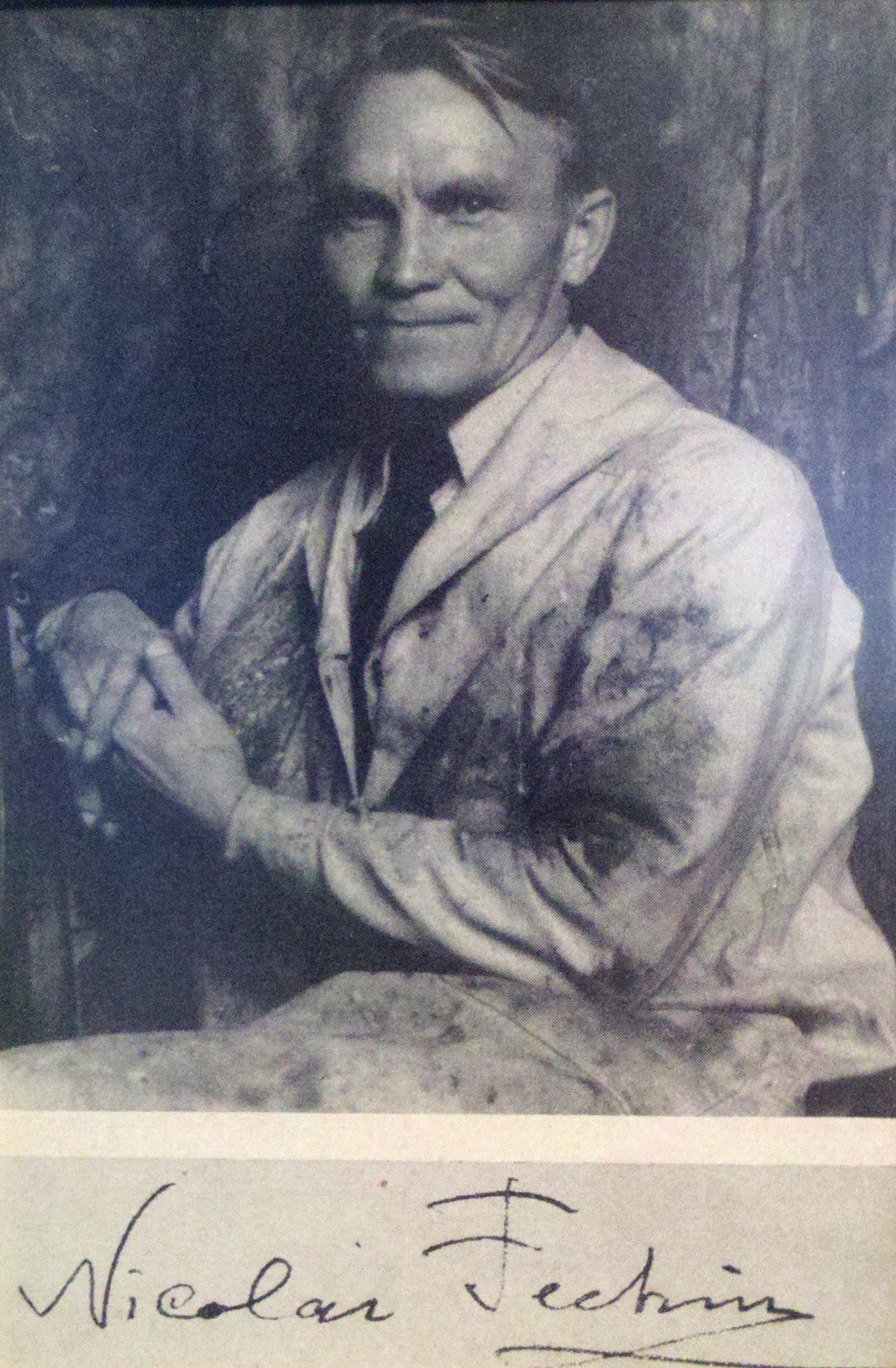

- Nicolai Fechin, photo courtesy of Taos Art Musuem

- “Alexandra on the Volga” | Oil on Canvas | 31.75 x 26.375 inches | 1912 | Private collection

- Fechin built all the home’s furniture and adorned it with carvings. A Russian half-gate separates the dining and living rooms.

- Nicolai Fechin’s home in Taos, now the Taos Art Museum at Fechin House, was a simple, two-room adobe. The artist added several rooms and many Russian-style windows, and in every room he created intricate woodcarvings, combining Russian, Moorish, Spanish Colonial, Native American and Art Deco influences. A curving staircase leads to an upstairs sunroom and bedrooms.

- “Father Fishing” (detail) | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 15.5 inches Private collection

- Fechin teaching at Kazan Art School. Photo courtesy of Taos Art Musuem

- “Eya in Judo Gi” | Oil on Canvas | 26 x 20 inches | Circa 1933 | Private collection

- “Russian Singer with Fan” | Oil on Canvas | 47.375 x 33.25 inches | Circa 1924 | Private collection, Photo: Robert Esposito, photoexpressionism.com

- The house is now dedicated to the work of the Taos Society of Artists and other early-20th-century Taos artists. Photos courtesy of Taos Art Musuem

- “New Mexico Landscape” | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 24 inches

No Comments