24 Jul A Deliberate Artist

DESPITE BEING A LIFELONG WANDERER, no one has stayed closer to home, literally, figuratively and emotionally, than Daniel Pinkham. A founder of the California Plein Air Society and the Portuguese Bend Artist Colony, Pinkham is an artist who is ever inspired by his surroundings. As a painter, Pinkham celebrates the new and the fresh within the familiar. Although he embarks on lengthy painting road trips with his wife, artist Vicki Pinkham, and spends two weeks every couple of years painting in Maine, Daniel Pinkham always circles back to his hometown landscape, his childhood friends and what he feels is his lifelong mission — to help preserve and protect the timeless quality of southern California’s Palos Verdes Peninsula.

“This peninsula has a fascinating history,” Pinkham explains. “Originally Spanish, it fell into the hands of ranchers in the early California days. In 1913, a group of investors bought 16,000 acres for $1.5 million. They hired the Olmstead brothers, who designed Central Park and Washington, D.C., to design a very beautiful planned community. They went to Italy to study plazas, churches and farmhouses, then came back to build. They abandoned the project after the Crash of 1929, but they’d already built plazas, chapels, schools and some homes. It’s beautiful and still has a rural feel. It’s like Carmel 50 years ago.”

Pinkham considers himself lucky to live in one of the project’s original homes, built in 1924. “We have an Italian chapel [a replica of a 16th-century chapel used by Michelangelo when he was working on the Sistine Chapel commission] on three acres on the coast of California. That’s because after there was a big landslide in the ’50s people didn’t want to build. Thirteen years ago the city was going to bulldoze our property and we stepped in to save it. It was falling down when we bought it. Everyone thought we were out of our minds. It became the headquarters of our artist’s colony, and we got very involved in preservation. It’s turned into a lifelong mission.”

The Portuguese Bend Artists Colony is a group of seven artists — Richard Humphrey, Stephen Mirich, Kevin Prince, Daniel Pinkham, Vicki Pinkham, Tom Redfield and Amy Sidrane — who paint together throughout the year. They create art that celebrates the natural environment while working to save it. Every year they mount a show, the proceeds of which go directly to the local land trust. “We formed the group in 1998 as a vehicle to help the Palos Verdes Land Conservancy protect open space,” explains Pinkham. “[So far] we’ve raised funds to purchase and protect 15,000 acres along the coast.”

That art could have that kind of lasting impact has been an unexpected benefit to someone who always knew he was meant to be an artist. “I started painting as a kid,” Pinkham recalls. “I always had a bent toward it, but didn’t realize until I ran into an English Antiques dealer that Pinkham means ‘painter of the village’ in Scottish. Albert Ryder Pinkham was the first American Spiritualist painter; he hangs in the Met, in the National Gallery. There’s something to say for lineage.”

Pinkham’s talent was recognized early. He was only in sixth grade when he was given the commission, to paint during class-time, two huge murals for his school. “They were jungle landscapes with exotic animals. It took six months to complete them and the school kept them up for years.”

Upon completion of high school, Pinkham enrolled at Art Center College of Design in nearby Pasadena. Within two years he had the opportunity to study with celebrated Russian painter Sergei Bongart; the hint of a scholarship was dangled before him. Sadly, his father’s illness and early death resulted in Pinkham packing away his brushes to run his father’s plumbing business. It would be 15 years before he could return to his art. When he did, he hit the ground running, studying first under Bongart. “It was an old-fashioned atelier. I started at the ground up, with drawing and making plaster casts. I spent one-and-a-half years doing black-and-white painting; that’s when you learn values, lights and darks. It’s key to being a strong colorist. It was very disciplined and very demanding and I wouldn’t trade it for the world. The greatest thing was to be able to see and learn how to live and survive as an artist. Sergei gave [his students] a sense of responsibility to protecting our artistic journey.”

Pinkham established his own art school and founded the first formal plein air painting organization in America. After four years of teaching, he and four other artists went to Europe to visit museums, study and paint. “Five of us lived in a Renault car with 300 wet paintings on the roof,” he laughs.

Upon his return, Pinkham says, “I didn’t want to teach. I wanted to hit the road.” For the next decade or more he spent at least six months a year traveling, including a month each summer in a cabin in Rocky Mountain National Park. He was “painting America,” sketching and painting on the road, then returning to a studio in his parent’s back yard to finish artworks. He taught himself wood carving and gilding during that time and still makes all his own frames. Galleries sought him out early on, and while the business has changed, he has always enjoyed good representation, frequent exhibitions and loyal collectors, for which he is grateful.

Tim Newton is Chairman of the Board of the Salmagundi Club in New York, whose annual American Masters show includes Pinkham’s work. “Dan can wax long and hard and he’s brilliant,” says Newton. “He’s a phenomenal artist who is influential. He’s inspired other artists and he’s a leader. He’s been a pioneer in making an impact both artistically and environmentally in his community. He has a strong spiritual base and he has his priorities right.”

“I have tried throughout my life to make decisions that protect my art,” explains Pinkham. “These are hard decisions. You go without a lot. I lived for years on very little money. I’ve painted in the middle of nowhere when it’s 20-below because for some reason I needed to get those colors, patterns and harmonies. That’s life’s journey, and you sacrifice a lot. I love to read about artists’ lives and how they survived. Our paintings are really a byproduct of how we live our lives.”

A gregarious personality, Pinkham has never hesitated to remove himself from every distraction for the sake of his art. “I love people, but I used to go backpacking and not see anyone for three weeks. You develop your intuition and your senses when you’re alone. Painting is a nonverbal language; you use visual skills and icons, or visual blueprints, to explain your voice. You become very attuned to shapes, patterns and colors, consciously and subconsciously. With so much media out there you kind of lose your sixth sense, but when you’re out in the wild you redevelop that muscle. That’s the beauty of going on the road. Life is so clear and much simpler.”

As soon as the restoration of the studio is complete, Daniel and Vicki Pinkham will build a new mobile studio and hit the road again. ‘We love being on the road and we get a lot of work done,” says the artist. “But it’s also in my nature to serve. It’s important to be part of the greater whole.”

For Pinkham, who has created so much, accomplished so much and has had a hand in preserving so much, his has been an ongoing journey that has been challenging and rewarding. “My life has been one of developing my faith and my spirit and my art and my friendships,” he reflects. “Life sometimes presents bills we find hard to pay — deaths, illnesses, the needs of others. Those have to come first, but I always find a way to come back to my art. I believe that the art is so important for addressing and representing our higher selves.”

WA&A Contributing Editor Chase Reynolds Ewald writes from her home in northern California. Her latest book, The New Western Home, was released last year.

- “Sublime Order” | Oil | 40 x 48 inches | Private Collection

- Painter Daniel Pinkham

- “The Guardian” | Oil | 30 x 24 inches | American Masters at Salmagundi Club New York

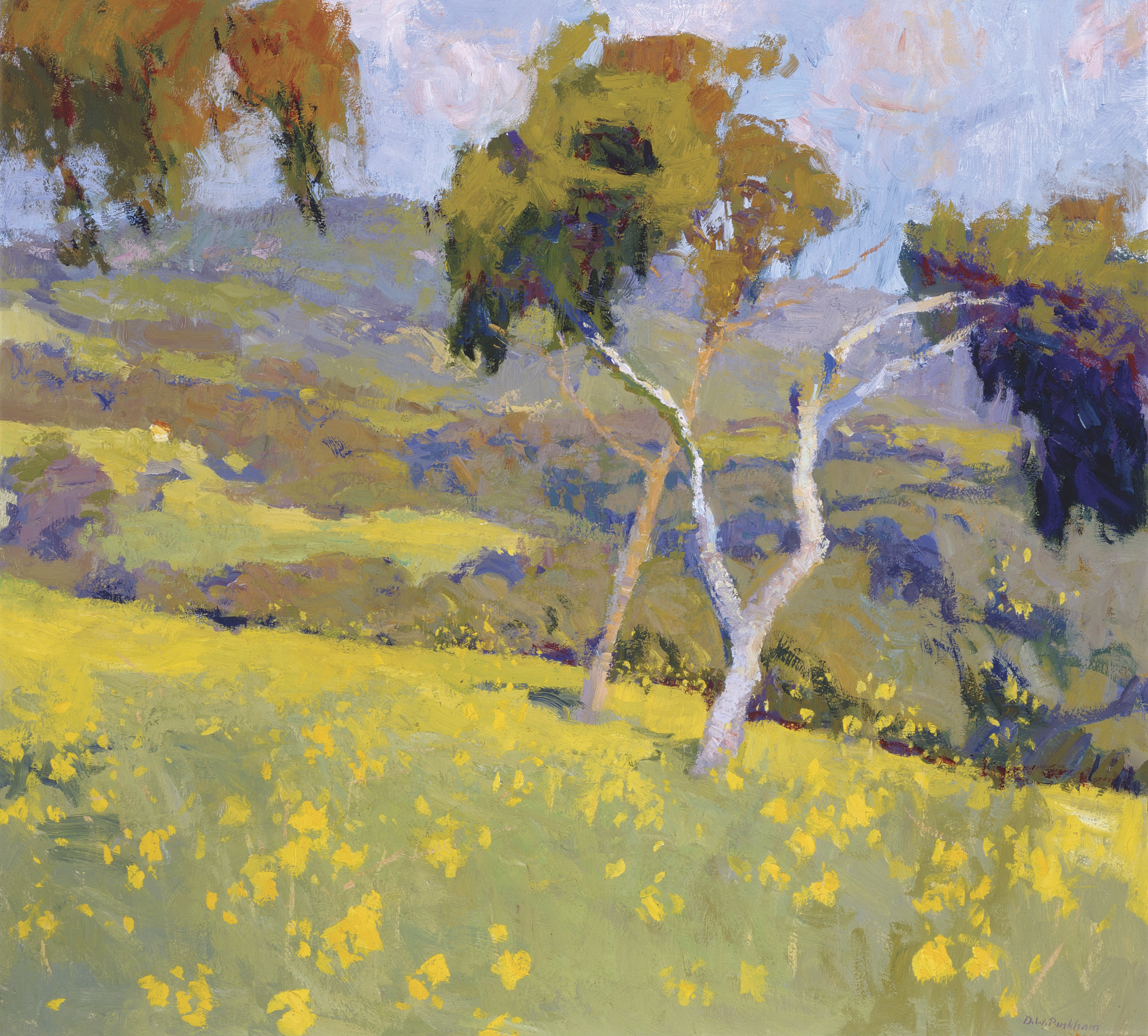

- “Spring in Portuguese Bend” | Oil | 26 x 28 inches | Private Collection of the Helen Schaefer Foundation

No Comments