24 Jul All for Art

PHILANTHROPIST ELI BROAD TOOK THE PODIUM, a whimsical lectern of balloon-shaped, vivid metallic colors designed by artist Jeff Koons. It was one of those blue-skied, indelibly clear southern California winter days, and the Broad Contemporary Art Museum was being inaugurated as the newest addition to the 20-acre campus of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“I believe Los Angeles can become the contemporary art capital of the world,” Broad began. It is a sentiment being bandied about a lot lately, and the creation of 60,000 square feet of new exhibit space wholly devoted to contemporary art seemed to cement the future importance of Los Angeles on the world art scene.

There’s always a certain degree of controversy when a major public building throws its doors open for the first time, and the inauguration of BCAM was no exception. Several weeks before the opening ceremonies it had been announced that Broad, the billionaire who’d been one of L.A.’s primary cultural philanthropists for decades, was not actually donating his collection to the building that bore his name.

“To Have and Give Not,” was the headline in The New York Times arts section.

But Broad had a really good argument for not donating his collection, which has grown to more than 1,400 works since he began buying (his first purchase, he mentioned, was a Van Gogh drawing, but he quickly realized that if he bought contemporary art he could actually meet the artists). No museum is large enough to show the Broads’ entire collection, and rather than have most of it in storage, in 1984 he and his wife, Edythe, created the Broad Art Foundation, which over the years has made approximately 7,000 loans of art to more than 400 museums.

Broad had footed the entire $56 million bill for BCAM, and had picked the architect, Renzo Piano, probably best known for his Pompidou Center in Paris, in the United States the New York Times building and the Menil Collection in Houston, and in Japan for the new airport in Osaka. Piano still seemed stunned by the swiftness with which things transpired.

“Everything happened in less than four years,” he said, shaking his head in wonder at the inaugural event. “Nowhere else in the world would this happen.” Normally it takes 10 to 15 years to complete a major cultural institution, he explained.

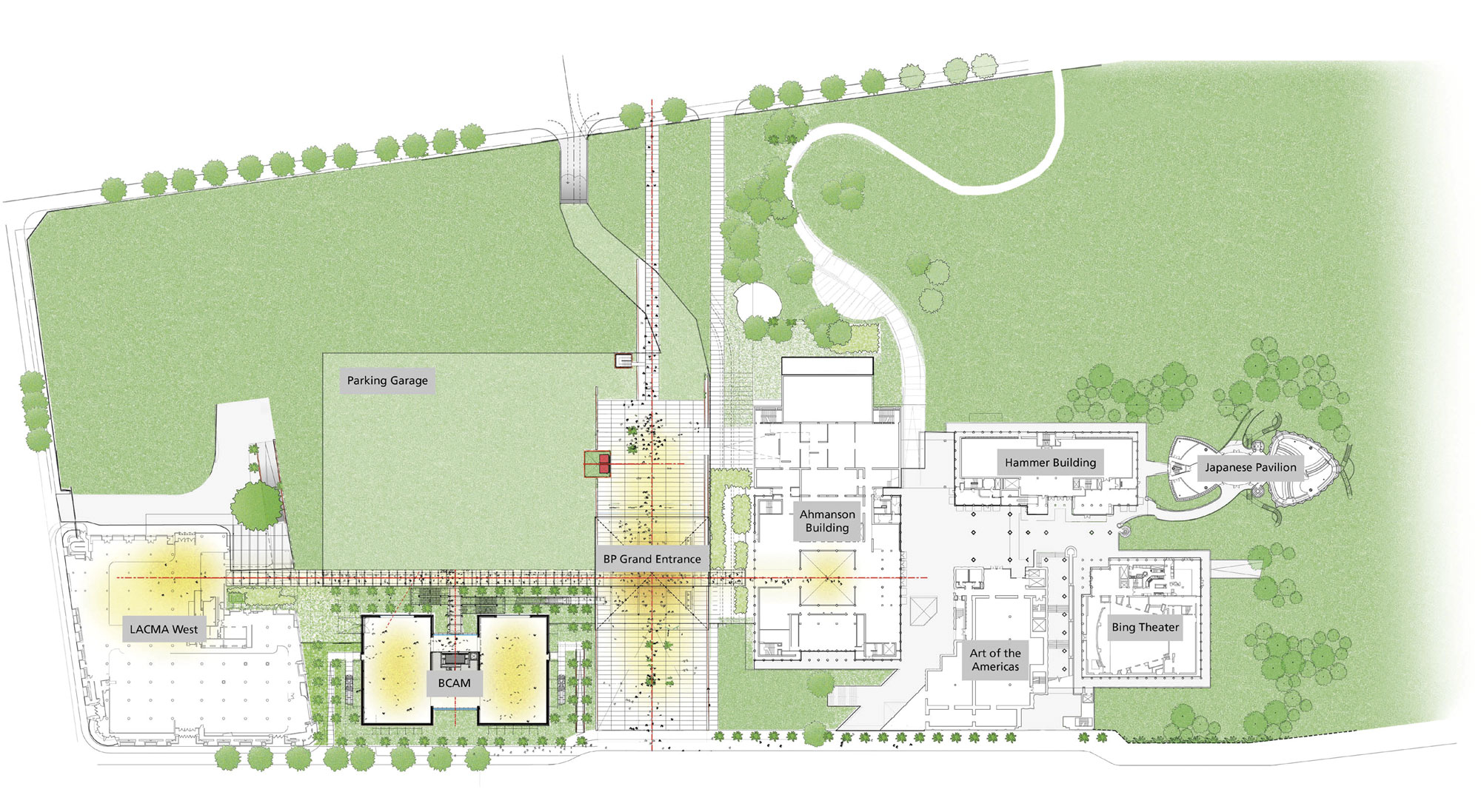

BCAM is part of Phase One of “Transformation,” an ambitious 10-year plan to transform the LACMA campus into a more cohesive unit. The museum, which is the largest encyclopedic museum in the West (and now the only encyclopedic museum with this degree of dedication to contemporary art), moved to its present site and opened to the public in 1965 in three buildings designed by then-prominent southern California architect William Perreira. The Neoclassical Modernist-style buildings surrounded a plaza reached by a grand staircase, and the complex was ringed by reflecting pools and fountains.

In 1986 the Anderson Building was added, along with a new entrance designed by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates. The museum was then essentially walled off from the street. The Pavilion for Japanese Art opened to much acclaim in 1988, the last design of renegade architect Bruce Goff. Then in 1995 LACMA acquired the former May Company department store, an example of late Moderne architecture, with a signature gold rounded corner framed in black glass. This brought the campus to 20 acres of completely unrelated architectural styles and intents. In the late ’90s the board of trustees began debating how best to create something cohesive out of the mess.

In 2001, some of the world’s foremost architectural stars, including Thomas Mayne, Daniel Lebiskind and the latest winner of the Pritzker Prize, Jean Nouvel, submitted designs for transforming the campus. Rem Koolhaus submitted the winning design, an ambitious glass tentlike structure — but it would have required the razing of the existing buildings, closing the entire museum for at least three years and the construction would have had to have been funded up front. The design promised to be an instant landmark, but the project was prohibitively expensive.

Things had ground to a halt when Eli Broad stepped in. He announced in 2003 that he would fund a new building. He picked Piano, who had chosen not to enter the original competition.

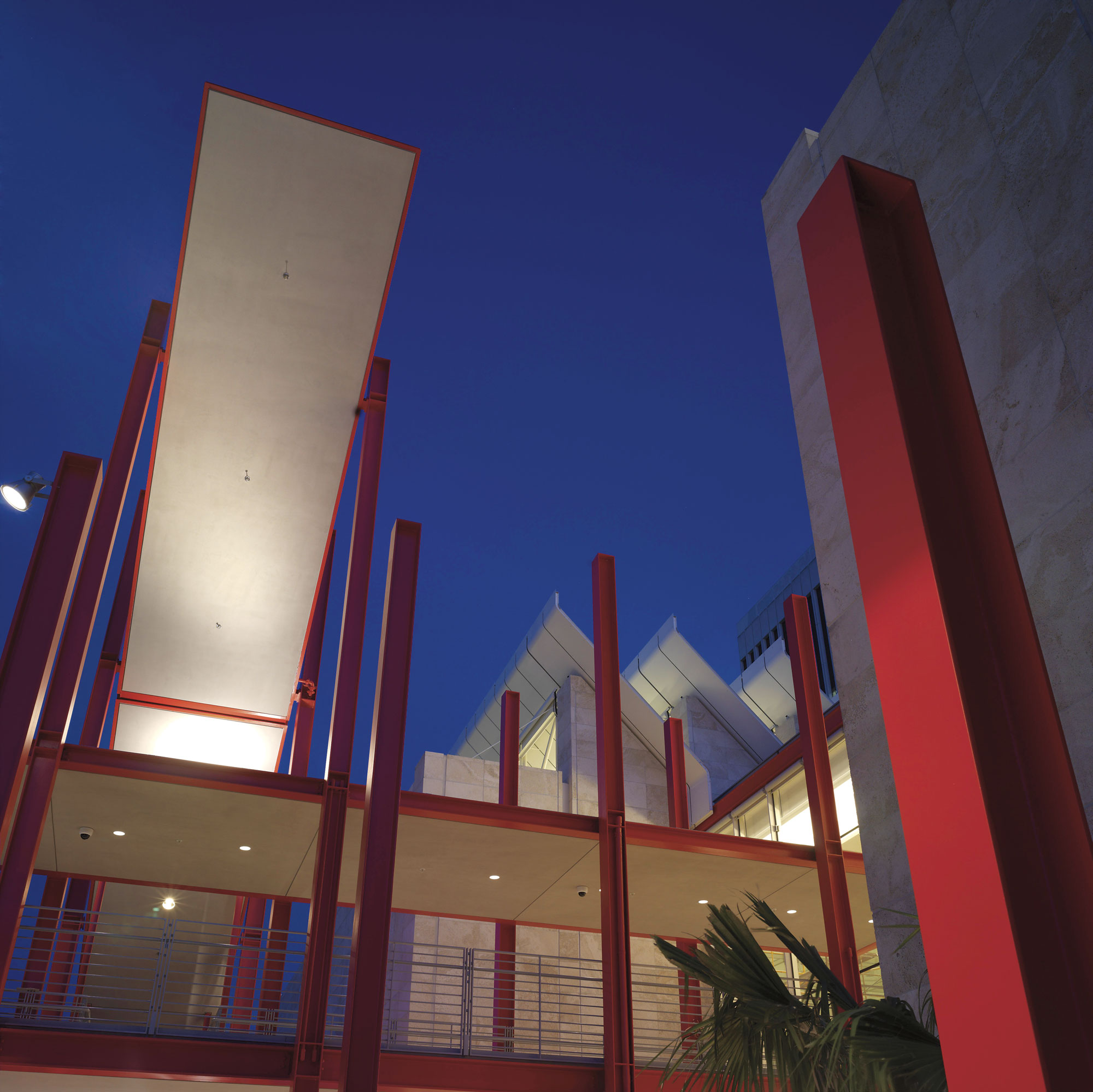

BCAM is a handsome, cream travertine-clad building that stands between the former May Company and the Ahmanson Building along Wilshire Boulevard. Great care was taken in selecting the travertine to prevent unwanted patterns or images from emerging. The building’s two wings are connected by glass windows and a center glass elevator the size of a stage. The three-story building is entered via a jaunty red-frame escalator to the third floor, so that the galleries are viewed from the top down. Once inside, it’s clear that the witty, jagged roof panels are in fact shades protecting the artworks from the natural light that flows throughout the top floor. The interiors are uninterrupted by columns or structural devices so they can be constantly rearranged for exhibitions.

“In this building all the energy goes to art,” Piano joked. “The only thing frivolous is a few toilets.”

The opening exhibition was hand-picked by new LACMA director Michael Govan and the staff. “They took nearly every piece of art in our home,” Broad sighed.

The Broads have extensive works from Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Cindy Sherman, Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The opening exhibition was an eclectic mix of the last several decades, including Rauschenberg, Twombly, Johns and Anselm Kiefer. California artists such as Ed Ruscha and John Baldessari were also included. Some critics carped that the opening exhibition was heavy on the 1980s and early ’90s, the boom years when art prices soared into the stratosphere. But in the end, there was little to complain about. The show had something for everyone.

The bottom two floors were taken up by two massive Richard Serra sculptures, one on extended loan from the artist, the other bought with the $10 million the Broads had donated for acquisitions.

BCAM is connected to the other buildings by a covered walkway and the BP Pavilion entrance. The campus is once more open to the street and art is visible to the sea of cars surging by. On the plaza leading to the new entrance is Chris Burden’s Urban Light, a maze of discarded period street lamps the artist (who’s mellowed considerably since having himself shot for a conceptual art piece) has collected. It’s beautiful by day, but lighted at night, it’s stunning. Artist Robert Irwin is designing palm gardens throughout the campus. Unfortunately, one of the more prominent public works on display, Jeff Koons’ huge (15 x 17 feet) Tulips has already had to be removed and sent back to the German fabricator for repairs, due to overt displays of affection from museum guests.

Phase Two will continue with another Piano-designed building, which may make up for the fact that the campus is still a series of disparate architectural styles. BCAM may be yet another building in yet another architectural style, but it’s a win-win for LACMA. Gallery space in the original buildings has been freed up to exhibit notable new collections. The public has been excited by and drawn to BCAM, and LACMA has been energized by the splashy debut.

“LACMA is the most important art institution west of Manhattan,” Broad said. And with the addition of BCAM, that seems less like bragging and more like a statement of fact.

Laurel Delp is a freelance writer living in Los Angeles.

- Site plan—LACMA campus © Renzo Piano Building Workshop

- Chris Burden’s “Urban Light”

- BCAM southeast facade ©2008 Museum Associates/LACMA

- Jeff Koons “Cracked Egg (Red)”, 1994-2006. High chromium stainless steel with transparent color coating. 18 x 48 x 48 inches (top), 78 x 62 x 62 inches (bottom). The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica ©Jeff Koons

No Comments