01 Sep Artistic Duality

AS A LONG TIME PAINTER OF THE AMERICAN WEST, Paul Calle is not a capturer of dramatic scenery or a depicter of finely etched Western characters, although his use of Western vistas is masterful and his subjects vividly rendered. Rather, Calle is a storyteller whose main interest is man in the moment. In his depictions of the fur-trader era in the Mountain West, Calle focuses on those individuals who had the fortitude and ambition to strike out alone into a great unknown of boundless landscapes, wild creatures, harsh weather, hostile Indians and dangerous terrain. His Western subjects, usually solitary figures, are presented not in heavy gunsmoke and full battle cry, but in the quieter moments, whose telling details represent the steady and bold steps by which the settling of a vast uncharted territory was achieved.

In Beyond the Ridge, for instance, two frontiersmen and a horse, their pack train behind them, pause atop a swell in the landscape. The immensity of the snow-capped mountains in the background and the riders’ outstretched arms pointing the way out of the scene serve to underscore both man’s insignificance in the surroundings and the intrepid nature of the explorer. Friend or Foe shows a lone rider shading his eyes with one hand as he looks into the distance. From the title we know that as much as this solitary figure yearns for a friend with whom he can share supper and swap stories, he must also be prepared to fight or flee. The image highlights the precarious nature of everyday interactions in the Mountain West, as well as the inherent loneliness of the mountain man’s quest.

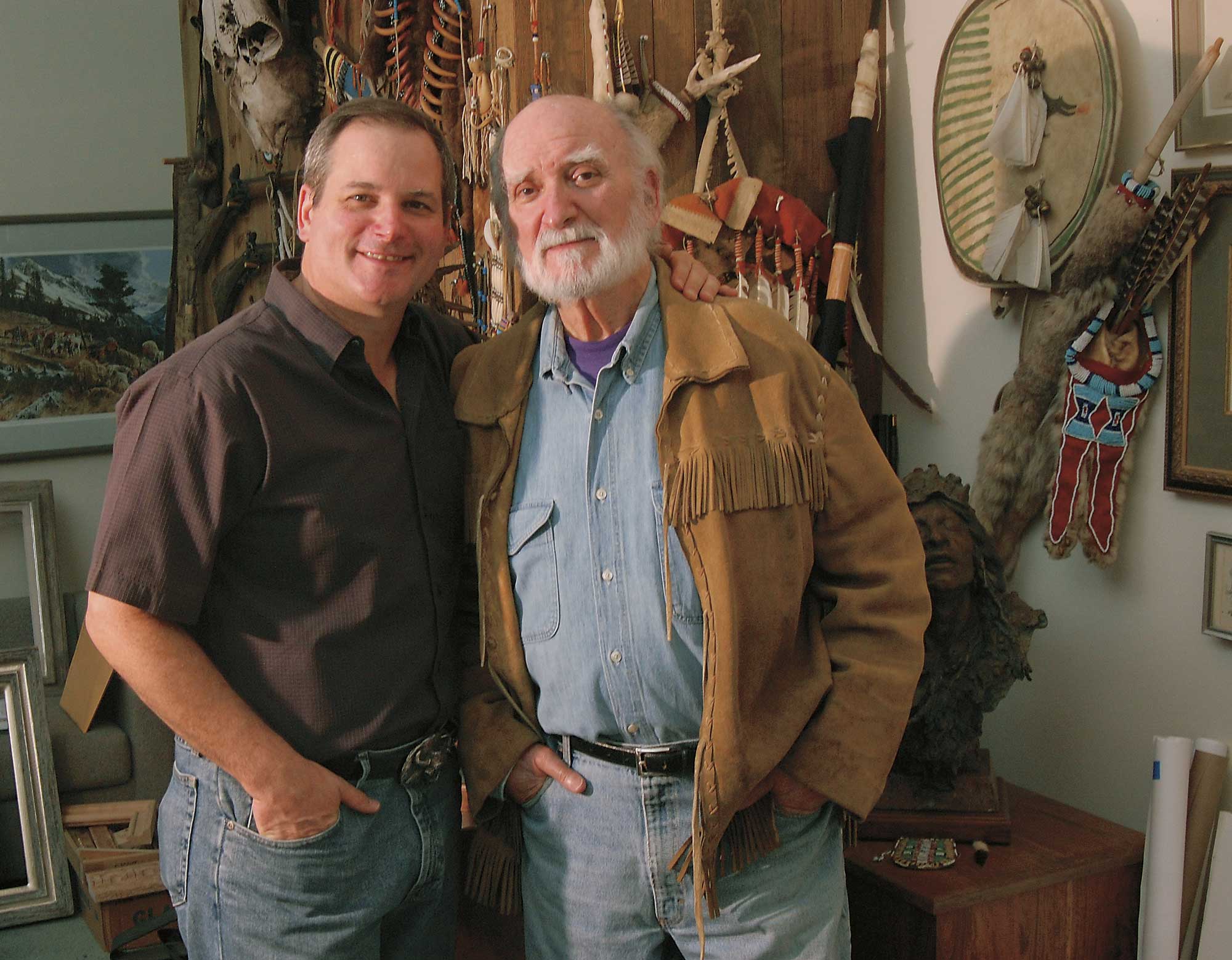

Calle likes winter scenes — he uses the red of a Hudson Bay blanket coat against a stark white background to great effect — and he is clearly fascinated by the men who dared to venture out alone into such unforgiving conditions. He excels in the portrayal of vivid, realistic details: in the scattered gear belonging to the men around a campfire; the downed geese at the feet of a winter hunter; fatigued horses, heads lowered; or a blacksmith working over an anvil inside a rough-hewn log cabin. This Easterner’s meticulous research — based on annual trips throughout the West, the employment of authentic Western characters as models, a comprehensive collection of artifacts and extensive reading — yields authenticity in his finished works.

Like so many other towering figures in the Western art world, Calle started his career as an illustrator. Born and raised in lower Manhattan, he was trained at New York’s Pratt Institute in the Saturday Evening Post tradition. But through membership in the Society of Illustrators, he had the opportunity at a young age to explore the West, courtesy of the U.S. government, with the Department of the Interior’s Artist-in-the-Parks program. As chairman of the program, he recalls, “I picked the parks and I picked the artists for the show every year. It was a marvelous opportunity. We went everywhere, from Mesa Verde to the Grand Canyon. I kept falling in love with the historic West, and my interest kept growing and growing.”

It wasn’t long before Calle was hanging out at modern-day rendezvous gatherings and had become friends with prominent Western artists like Frank McCarthy. By 1975 he’d been asked by a Texas gallery to submit works for a convocation of Western artists featuring luminaries like Howard Terpning and Tom Lovell.

“I said I had to think about it,” Calle recalls. “My wife said, ‘You always wanted to do this. This is your chance!’ I did six large drawings — of mountain men, cowboys, Navajo. I was told, ‘If you sell one, it’s a success.’ We sold out in the first half hour. That’s how it started, and I never went back to commercial art.”

Calle’s work is recognizable by his unique style, most notably his discernible brush and pencil strokes, at once authoritative and expressive. But what sets Paul Calle apart is his duality. He’s not only a painter but a pencil artist; in his hand the humble sketching tool is a valid artistic medium in its own right. He’s not only an artist but a writer, the author of two books and the subject of a third. And in his art, Calle has three distinct bodies of work — Western paintings and drawings, space art and stamp design — and three entirely different groups of collectors. Paul Calle is certainly the only Prix de West Award winner who’s had a one-man exhibition at the Museum of Flight and been celebrated by philatelic associations. In partnership with his son, artist Chris Calle, theirs is and might well remain the only father-son design team in the history of U.S. stamp design.

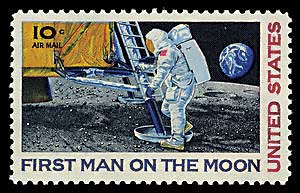

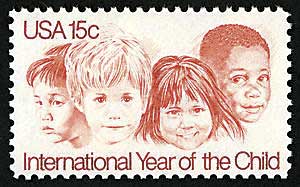

Calle has designed 30 stamps in as many years. His subjects range from the Vietnam Memorial to the International Year of the Child, and include notable Americans such as Douglas MacArthur, Helen Keller and Frederic Remington. His most exciting commissions were the result of his long-term relationship, since 1962, with NASA. One of the most widely disseminated artworks in the world, in fact, was Calle’s First Man on the Moon stamp, published to commemorate the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing; 150 billion of these 10-cent stamps were produced.

Calle’s twin fascination with the historic West and space travel may seem disparate. (“People who know him from the West don’t know his NASA work,” says his son Chris. “And people who know him from NASA don’t know his Western work.”) But there is a basic relationship between them which goes to the heart of this artist’s lifetime achievement. Over a 50-year career Calle has been inspired by telling moments in historic transitions, from the mundane — frontier men around an evening camp — to the momentous: man’s first step onto the surface of the moon. But both chronicle man’s quest to explore. As Chris Calle points out, “My dad has always equated John Colter’s moccasin print in the Yellowstone with Neil Armstrong’s boot print on the moon.”

Calle’s work resides in the permanent collections of many institutions and major private collections, including the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, the U.S. Department of the Interior and the Gilcrease Museum. His artistic legacy is ensured by his two books on art. Paul Calle: An Artist’s Journey, written with author Pam Hait, explores the artist’s inspirations and life work; it won the Benjamin Franklin Award for Fine Arts in 1993. The Pencil, which explores pencil drawing as an artistic medium, has enjoyed widespread influence, having been translated into French, Russian and Chinese. Due out soon is a book by Chris Calle: Celebrating Apollo 11, The Artwork of Paul Calle.

Still painting in his 80s, Paul Calle remains vigorous and confident, both in brushstrokes and demeanor. Although he deeply feels the loss of his wife and longtime partner, Olga, he is close to his three children. Says his son Chris Calle, a noted artist in his own right with whom the elder Calle shares a studio in Connecticut, “The interesting thing about my dad’s work now is that at age 81 he hasn’t lost a thing.”

Carrie Ballantyne, a fellow Prix de West winner who also works in pencils and oils, echoes this. “Paul Calle is a very smart man with a great work ethic and tremendous diligence. His vision and passion for art is quite evident, and just as strong today as ever.”

“There was a rumor that I’d died,” Paul Calle notes wryly. His reaction? “I did a 40-incher for the Prix de West so that people would know I was still here.”

Clearly Calle realizes how fortunate he is to have achieved so much through his art, to have touched the lives of so many people, to have spent his days doing what he most enjoys and to have partnered in his artistic life with a wife who supported and encouraged him every step of the way and a son who followed in his footsteps. “How many people,” he reflects, “love what they do for a living?”

Perhaps the greatest gift is having had the chance to document history, in addition to witnessing it through his art. “I think for me, if I had to state a goal,” Calle wrote in his foreword to The Pencil, “my aim would be to help keep alive that huge reservoir of our past, to draw strength and sustenance from it, to build upon it in ways that are new and different, but not reject it.”

Clearly, Paul Calle has achieved — and surpassed — that goal.

Chase Reynolds Ewald writes from her home in northern California. Her latest book, The New Western Home, was recently released by Gibbs Smith, Publisher.

- Down from the High Country | Oil | 2009

- Voyageurs and Waterfowl | Oil | 1998

- The Great Moment | Oil | 1969

- Left, Chris Calle, right, Paul Calle. Photo by Daniel J Kropas

- Something for the Pot | Oil | 2006

- Man of the Mountains | Graphite Drawing

No Comments