04 Aug Beyond Skin Deep

THIS SPRING, A CROWD GATHERED at Sotheby’s New York City auction house for its Contemporary sale. Two Studies for a Self-Portrait, by figurative painter Francis Bacon [1909–1992], drew special attention. After rapid-fire bidding, the 1970 painting (with an estimated value of $20 to $30 million) hammered at a final price of $34.9 million. The intense interest in this work stems partially from its rare availability — it was owned by one family since its creation and only exhibited twice — but it also emphasizes the unique appeal and potential value of artists’ self-depictions.

Throughout history, self-portraits have provided art lovers with a window into the lives of the masters. They allow us to feel a connection to those whose artwork we revere. Artists have always made use of their ready availability as models, creating self-portraits to showcase their skills, to cast themselves in heroic or mythic roles, to work out the details of a specific pose, or to commemorate events and the passage of time.

Although there are far earlier examples of self-portraiture dating back to ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, it was during the Renaissance that the genre gained traction. Artists included their own images in historic and biblical scenes, as Michelangelo [1475–1564] did when he gave his likeness to the flayed skin held up by St. Bartholomew in The Last Judgment on the end wall of the Sistine Chapel.

Some of the most famous self-portraits, by masters such as Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn [1606–1669] or Vincent van Gogh [1853–1890], continue to draw crowds at museums around the globe. We see not only their craftsmanship, but we also gaze deeply, attempting to unravel the mystique of these talented beings: What were they like? What clues are offered in their portraits that tell us more about the artists and their lives? What were they thinking and what did they hope these paintings would reveal to viewers?

Rembrandt left us an invaluable visual diary of his career that dates from its outset in the 1620s until his death. Although numbers vary, it is estimated he depicted himself in 40 to 50 paintings and approximately 32 etchings and seven drawings. Perhaps his most famous is the 1665 painting Self Portrait with Two Circles, which shows the artist holding his palette, brushes and maulstick with two enigmatic circles in the background. He is depicted as somber, having suffered deep personal tragedy with the death of his three children, his wife and his mistress a few years earlier. The magic of Rembrandt’s chain of self-portraits is that we see his appearance change and intuit the character and personality in each work, fulfilling a sense of the man behind the brush.

Another Dutch painter among history’s prolific self-portraitists is Post-Impressionist van Gogh. He produced more than 30 self-portraits over the course of his career, and it’s believed that he used these as a means of strengthening his skills for a lack of available models. Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear is of particular interest. Painted early in 1889, weeks after returning home following the episode in which he cut off a portion of his left ear, the portrait shows a three-quarter view of the artist in a room of the Yellow House in southwestern France. The artist wears a green overcoat and a fur-lined cap; there’s a bandage on his right ear, a fact that’s attributed to van Gogh working from a mirrored image.

Born during the latter years of van Gogh’s career, Pablo Ruiz y Picasso [1881–1973] became one of the most innovative and influential artists of the 20th century. Although grounded in classical traditions, he soon explored an astonishing range of styles. His many self-portraits provide a cartographic montage of his career, keeping in mind that in many of his post-Cubist works he symbolized himself as the “painter” or the “minotaur” rather than creating a literal depiction. From the melancholia of his 1901 Self Portrait during his Blue Period, to his Cubist self-depictions only a few years later, until one of his last — Self-Portrait Facing Death, produced in 1972 with crayon on paper, his features reduced to deep creases and scribbles — Picasso’s self-portraits reveal something of both his physical and emotional self.

This turn toward self-portraits as a record of an artist’s emotional state made its appearance alongside the advent of psychology, evolving ideas about individualism, genetics and philosophy in the 20th century, when more personal representations in portraiture gained popularity. Self-portraits became playful, serious, shown in thought-provoking settings or, increasingly, as a way to suggest a point of view about gender, race, religion and politics.

With the reconceptualization of identity and the reinvention of figurative art in the mid-20th century, self-portraits by such artists as Andy Warhol [1928–1987], with his mass-produced replications of self, and the enormous photorealistic portraits of Chuck Close [b. 1940] drew new attention to the genre. Close’s 1967–1968 Big Self Portrait marks a significant point in his style, featuring an unrefined, head-on view rendered photorealistically in black and white. And in the 1980s, the art of Frida Kahlo [1907–1954], who had made an examination of her physical pain and psychological distress the subject of painterly scrutiny in the 1930s and 1940s, gained cultlike popularity.

21st Century Reflections on a Painterly Tradition

Today, the popular trend of “selfies,” snapping photos of ourselves with our phones at every turn, can distract us from realizing the rich, historic heritage of artists sharing their own image. Self portaits are a revealing act, unlike selfies, they are not just saying, “This is how I look.”

Self-portraits often make powerful statements as the artist is released from expectations that accompany commissioned portraits, says Edward Jonas, chairman of the Portrait Society of America. Jonas points out that the familiarity of the subject can result in an increased boldness of brushwork and experimentation in color and composition.

“As the work evolves through the creative process, a current of subconsciousness is continually and subtly having an influence upon each stroke and decision,” Jonas says. “This unique ‘artist as creator and subject’ can result in exceptional works of emotional and artistic revelation.”

Santa Fe artist Michael Bergt created a series of iconographic egg-tempera paintings, following in the footsteps of the Renaissance tradition of self-portraiture. He portrays himself as a modern-day St. Michael in St. Michael of the Apocalypse. For Bergt, this mythological depiction represents a tribute to his efforts “to discern good from bad, light from dark” and, akin to St. Michael in the biblical sense, he was “weighing the values he sees around him.”

Utah artist Jeff Hein echoes this convention, painting himself as Lazarus in Raising of Lazarus because of his own near-death experiences. In this way, he brings personal meaning to the powerful biblical scene.

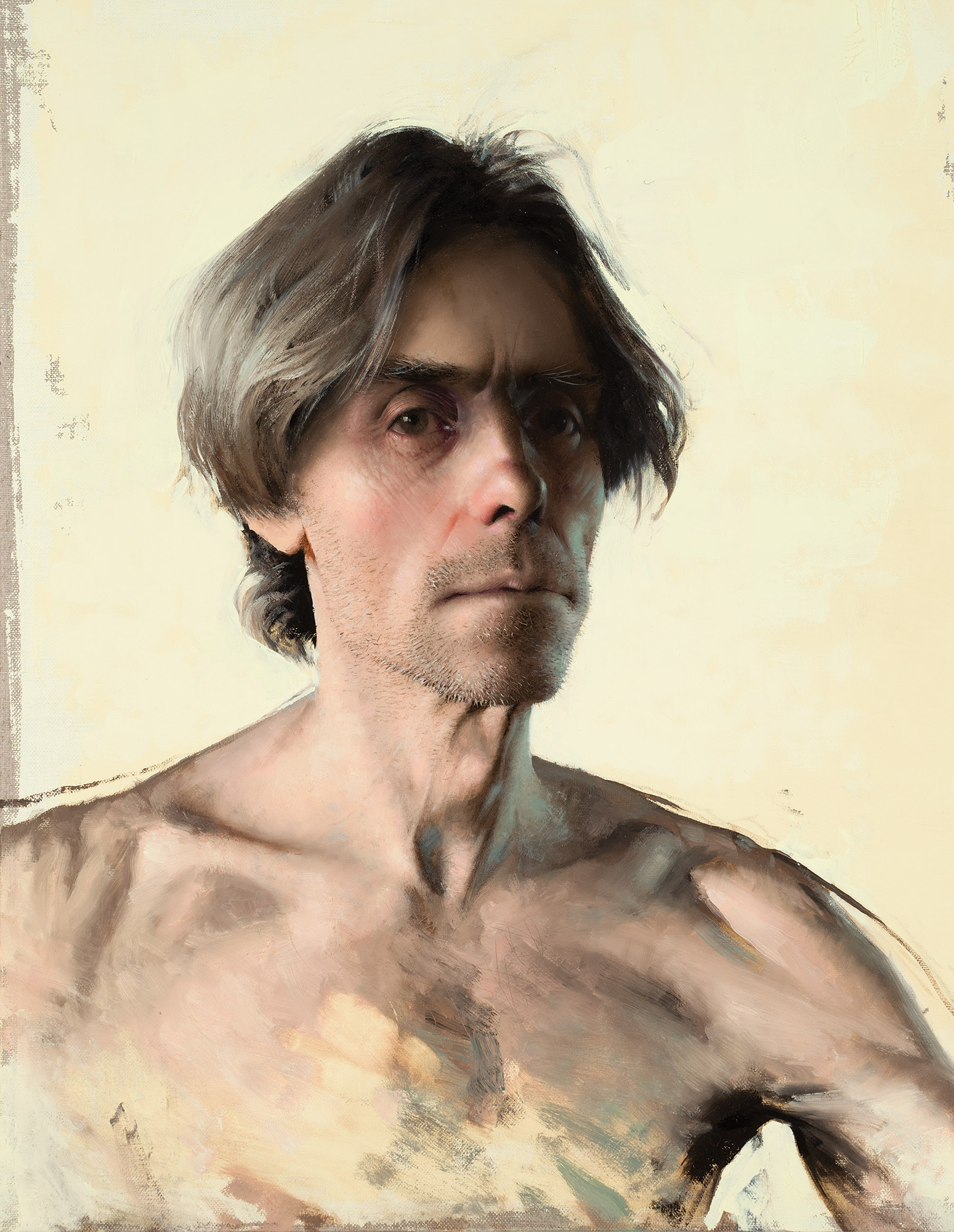

Denver artist Daniel Sprick, renowned for his skilled craftsmanship, says that a self-portrait can add “an interesting element to a body of work.” In his 2014 solo exhibition at the Denver Art Museum, Daniel Sprick’s Fiction: Recent Works, he included a self-portrait among a remarkable collection of more than 40 portraits and still life paintings. He painted himself without adornment. There are no clues to his life or mood. He purposely chose to present himself as simply a part of the chorus of unique and unembellished humans showcased in the exhibit.

A special event, spiritual journey, self-examination or the desire to explore a composition are all catalysts for painting oneself onto canvas. Travis Collinson’s self-portraits are “usually tied to a personal experience, idea or moment of self-reflection,” as in Study for the Blue Rider.

Ann Gale also creates self-portraits when she is going through a change in her work or life. Working from observation over extended periods, accumulating marks of color, she strives to “document the sensations of flesh, light and space, as well as the psychological and visual pressure of my own gaze.” In recent works, such as Self-Portrait with Purple, she focuses on “the fragile and momentary nature of perception.”

Sculptor Alicia Ponzio was awarded first place in the 2014 Portrait Society of America’s International Portrait Competition for In Recent Days. She worked on this piece, she says, “after relocating my studio from Florence, Italy, to San Francisco, California. I’d been through a great deal of change … trying to find my footing in a different city, environment and situation. I felt the need for honesty and self-examination. I wanted to portray myself, my age and my fatigue in a moment of hesitation.”

Painting one’s self is challenging. “You have to readjust your head every time you put a brushstroke down,” says Olga Krimon, whose Self-Portrait with Peonies was awarded a Certificate of Excellence in the 2015 Portrait Society’s international competition. “I wanted to appear strong, and yet I am vulnerable too. I wanted my portrait to convey that through the subtleties of the skin and fabric, the sensitivity of the flowers.”

Carla Crawford completed her luminous Half Light because she wanted to show herself working in her studio. “I rigged up two mirrors to create the angle I wanted and I painstakingly assumed the same pose hour after hour,” she says. “The figure’s extreme three-quarter stance, in the act of turning away into shadow, interested me for what it allows the viewer to see and assume, but also for what it keeps unseen and unknown.”

Celebrating a moment, a career success or marking the passage of time were inspirations for Anna Rose Bain, Andrea Kemp, Mary Sauer and Sadie Valeri. For example, Bain says her recent self-portraits often document the emotional, physical and artistic changes that have taken place since becoming a mother. “Motherhood was painted when my daughter, Cecelia, was 22 months old. I wanted to depict her innocence and my guardianship of it. She was at that classic toddler stage where she wanted to hold on tight but pull away at the same time — but as her mother, I’m not ready to let her go,” Bain says.

Self-portraits lift the veil and show us important personal moments in an artist’s life, exposing values and intimate details that can make us cherish works by that artist even more deeply. When patrons begin collecting a specific artist’s output, they long to know more — how the artist came to be so talented, what their life is like, who is the person behind the easel, the hammer and chisel, the modeling tool. Self-portraits created over a lifetime provide a continuous thread of revelation, an enticing and vulnerable story of the human experience.

- Jeff Hein, “Raising of Lazarus” (detail) | Oil on Canvas | 96 x 72 inches

- Carla Crawford, “Half Light” (detail) | Oil on Linen | 19 x 14 inches

- Mary Sauer, “A Little Bit of Everything, a Great Deal of None” (detail) | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 18 inches

- Andrea Kemp, “Airplanes” | Oil on Paper | 13 x 13 inches

- Anna Rose Bain, “Motherhood”(detail) | Oil on Linen | 30 x 20 inches

- Alicia Ponzio, “In Recent Days” | Stained Plaster | 22 x 10 x 9 inches

- Olga Krimon, “Self-Portrait with Peonies” | Oil on Belgian Linen | 36 x 48 inches

- Travis Collinson, “Study for the Blue Rider” | Acrylic on Linen | 15 x 13 inches — Courtesy of Anglim Gilbert Gallery

- Michael Bergt, “St. Michael of The Apocalypse” | Egg Tempera | 17 x 13 inches

- Daniel Sprick, “Self Portrait” | Oil on Board | 20 x 16 inches

- Ann Gale, “Self Portrait with Purple” | Oil on Linen Wrapped Board | 14 x 11 inches

- Sadie Valeri, “Self Portrait at 41 in the Studio (With Dog)” | Oil on Linen | 31 x 40 inches

No Comments