01 Dec Painting his Passions

Eldridge Hardie is not one to take the path of least resistance. Whether it’s Atlantic salmon or permit, some of his favorite places to fish are those in which landing two or three fish in a week constitutes a good catch. He grins as he talks about keeping up with his son while hunting waterfowl in Saskatchewan. “At 70, I was the old guy,” he says. “Getting up at four in the morning … after five days I was just worn out.” He shakes his head at the memory, but something tells me he’d be glad to do it all over again.

This persistence shows up in his art as well. Hardie seems to almost embrace those days when he has to toss a watercolor aside because it isn’t going well. “You might be a whole day in, and have to start over,” he says, “but the retry is much better and it was worth a day to get it right.”

There is certainly no doubt among collectors and sporting enthusiasts that Hardie has indeed gotten it right. He has illustrated more than 25 books about outdoor sport, raised thousands of dollars for conservation causes by donating his art and has been featured in countless galleries, museums and exhibitions. Hardie has been honored by the Fresh Water Fishing Hall of Fame, the Atlantic Salmon Federation and was the inaugural Trout Unlimited Artist of the Year.

Despite decades of accolades, the artist is impossibly humble, pointing out that his wife, Ann, who runs the business side of the operation, is the indispensable one. “She does just about everything but paint the pictures!” Hardie says, claiming that he actually doesn’t work very hard.

Curators, gallery owners and anyone taking a casual tour through his Denver studio would quickly refute such a claim. Files of carefully collected reference materials and notes fill the sunny upstairs space. Dated binders are full of fragments of pieced-together photographs and sketches with numerical indicators that translate into dozens of shades of blue or green. The notebooks make for fascinating reading, as anyone who has pored over Hardie’s 2002 book The Paintings of Eldridge Hardie: Art of a Life in Sport can attest. The last pages of the book feature these sketches from the field, thumbnail compositions and handwritten notes about how the paintings should come together.

Michael Paderewski, owner of The Sportsman’s Gallery and Paderewski Fine Art, with locations in Beaver Creek, Colorado, and Atlanta, Georgia, cites this as one of many reasons he spent several years convincing Hardie to show at his gallery. “The construction of the painting — the field sketches, how they translate to scale within the size of the piece and how it comes to full and final execution — is something that Eldridge has broken down into a fine science and is very, very methodical about,” Paderewski says, his voice full of admiration for the painter he calls “the next Ogden Pleissner.”

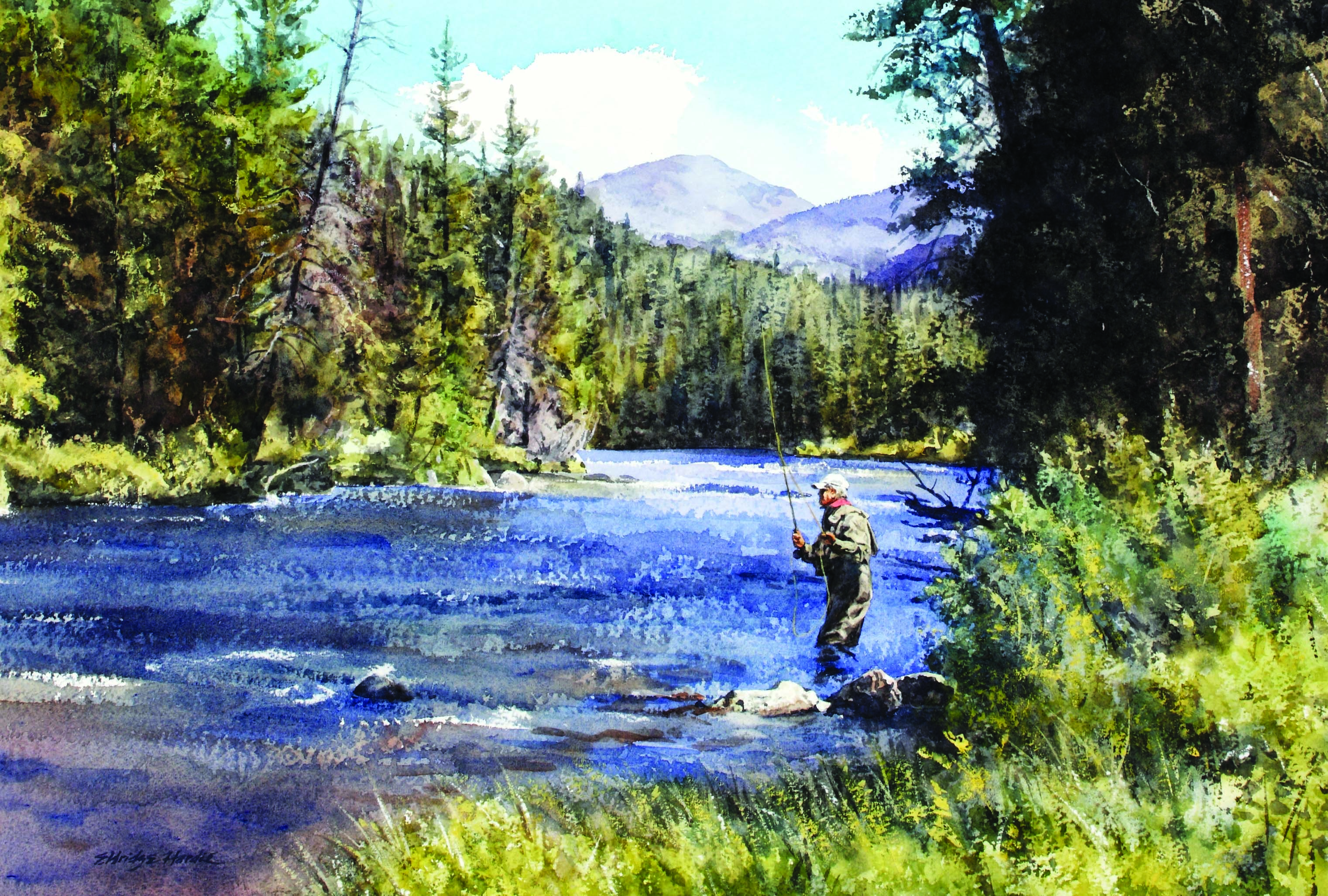

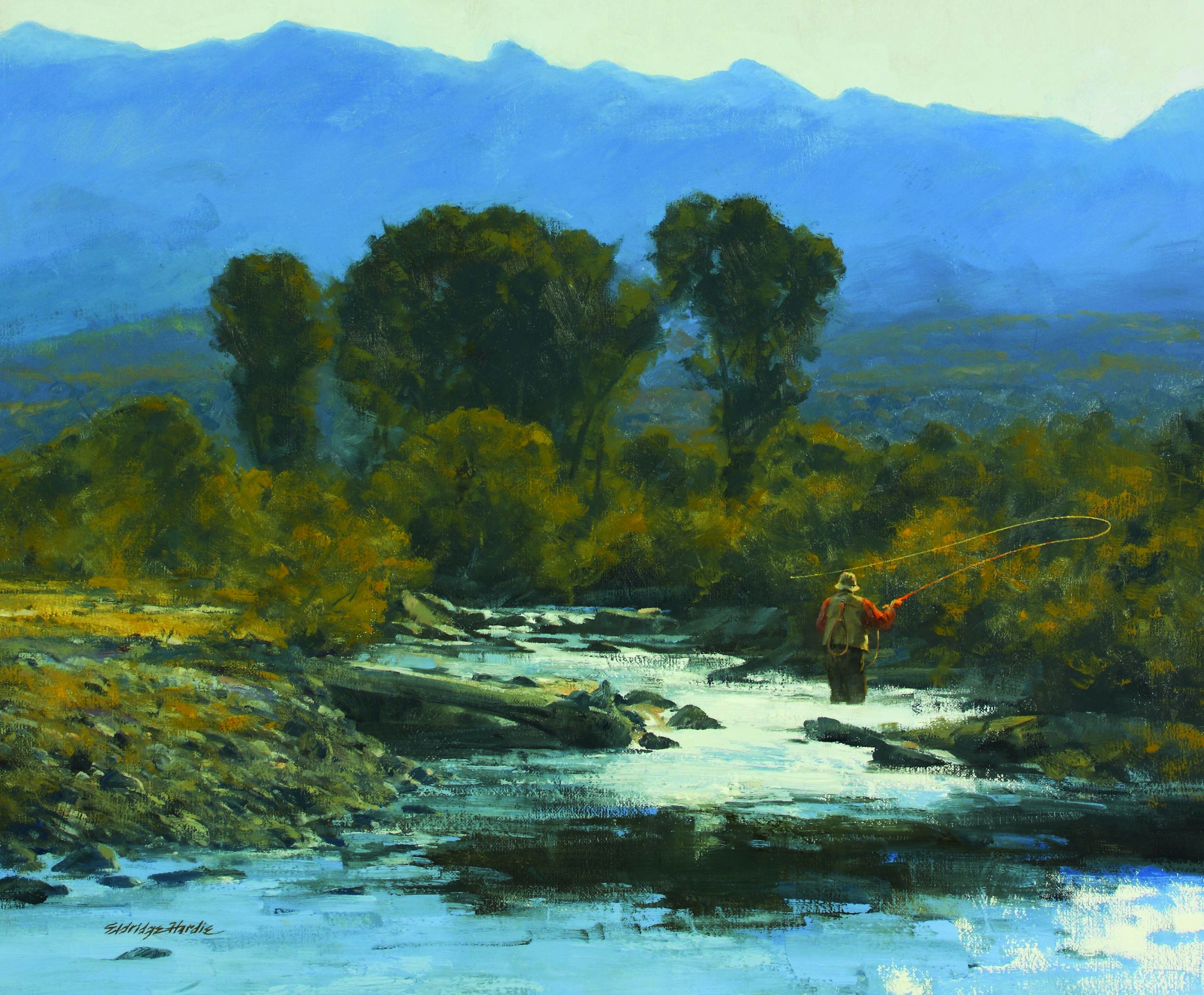

Such a meticulous attention to detail coupled with Hardie’s intense passion for his subject matter makes it impossible to talk about the artist without the word “authentic” coming up again and again. Most of his collectors are sporting men and women themselves who recognize Hardie’s passion for hunting and fishing in the subtleties of his work. His paintings evoke the best memories of autumn days spent hunting or early mornings wading in a creek.

“A lot of fishermen have been in here, just drooling,” says Connie Mohrman, exhibits manager at The Wildlife Experience in Parker, Colorado. This is exactly why she recently mounted a one-man retrospective of 32 of his oils and watercolors spanning 40 years. “People interacting with nature is really where we are going,” she says of the Wildlife Experience’s goals. “Not only do we want people to look at beautiful pictures, but we want them to imagine themselves in the out-of-doors.” Hardie’s work is perfect for this. His paintings are the ones you want to step into, sidling up to a figure with your own rod or decoy.

Bubba Wood, owner of Collectors Covey in Dallas, Texas, cites Eldridge’s passion for sport as the reason for his success. “Eldridge Hardie is the real deal,” says Wood. He explains that it’s easy enough to set up a scene with dogs and quail. Any artist could photograph the scene and then turn around and paint it, but only a real expert in the field would know how to bring in the excitement, the lifted ears of the dogs and other true elements into the painting. “I know of no sporting artist that has spent more time in the field than El. The authenticity that we sportsmen relate to in his wonderful art reflects those long hours.”

Those long hours hunting and fishing with clients as he’s gathering material work out to be a pretty good life if you ask Hardie. Conversations about commissions turn into stories of grouse hunting in Scotland, trips to Georgia to hunt quail and fly-fishing expeditions in the saltwater flats of Belize and the Bahamas. “Growing up, I would devour those outdoor magazine stories,” Hardie says, “and I just thought all that stuff would be so neat to do. I’d think those artists were pretty lucky. My imagination wasn’t big enough then to realize I’d be doing it someday.” Perhaps Hardie’s joy, wonder and appreciation for his experiences are what make his paintings so enticing.

Trying to tease out of Hardie which is more fulfilling — the sport or the art — is impossible. In one breath he’ll talk about how he and his brother used to hightail out of the school parking lot to go dove hunting in El Paso. And then he’ll talk about his uncle Eldridge King, a professional illustrator in New York. At 6 years old, Hardie remembers watching his uncle complete a painting, immediately knowing he was also meant to paint. “Fortunately, I had good influences early on: parents that liked pictures and a father who was just enough of a sportsman to influence my path. My uncle and El Paso’s Tom Lea, a well-known painter and author and family friend, were my real-life career role models.”

Art school at the School of Fine Art at Washington University in St. Louis was interspersed with summers as a guide on Yellowstone Lake. Setting down a fly rod to pick up a camera is just as common as spending the day hunting without ever pulling out a sketch pad. “As long as I’m going to work hard at making paintings, I’m going to paint something that’s interesting to me, too,” Hardie says. “I paint my vices.” This must be where the authenticity in Hardie’s work comes from. The art and the sport are irrecoverably intertwined.

- “Dry Fly Morning” | Oil | 20 x 24 in

- “October Partridge” | Watercolor | 14 x 21 inches

- “Bobwhites–A Pair” | Oil | 9 x 12 inches

- “Bobwhites and Pointers” | Oil | 24 x 36 inches

No Comments