29 Dec They Walk Among Us

WHILE ICONS OF ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM SPENT THE 1950S GAIMING FAME for the bold and the cheekily beautiful, artists whose work was ill-suited to the mantle of Modernism were methodically laying the groundwork for a latter-day Realism whose reach today stretches from urban centers in the East to the wilds of the American West.

Among the beneficiaries of the postmodern movement is a cadre of wildlife sculptors in western states whose work is reshaping the national landscape, one bronze at a time. From plazas to national parks and from high-end housing developments to industrial zones, public and private spaces are being ornamented with outsize animals in a trend that can trace its recent roots to the acclaim that attended the 1984 unveiling of Robert Glen’s larger-than-life bronze mustangs galloping through a granite-encased office complex in the affluent planned community of Las Colinas in Irving, Texas.

The installation reopened an avenue for traditional bronzes, acting as a stylistic statement that it was safe to return to realism and invoking an all but audible sigh of relief among some artists and patrons. “It was one of the first of its generation, the progenitor of a movement that has spawned realistic, super-size grizzles, moose, bison,” says Michael Timmons, head of Utah State University’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning. It is a movement in reaction — but not repudiation — to an attitude about public art which suggested that only the unenlightened failed to applaud extremes in abstraction. “Things reached that point where people were turning and saying, ‘What the heck is that?’ ” says Timmons.

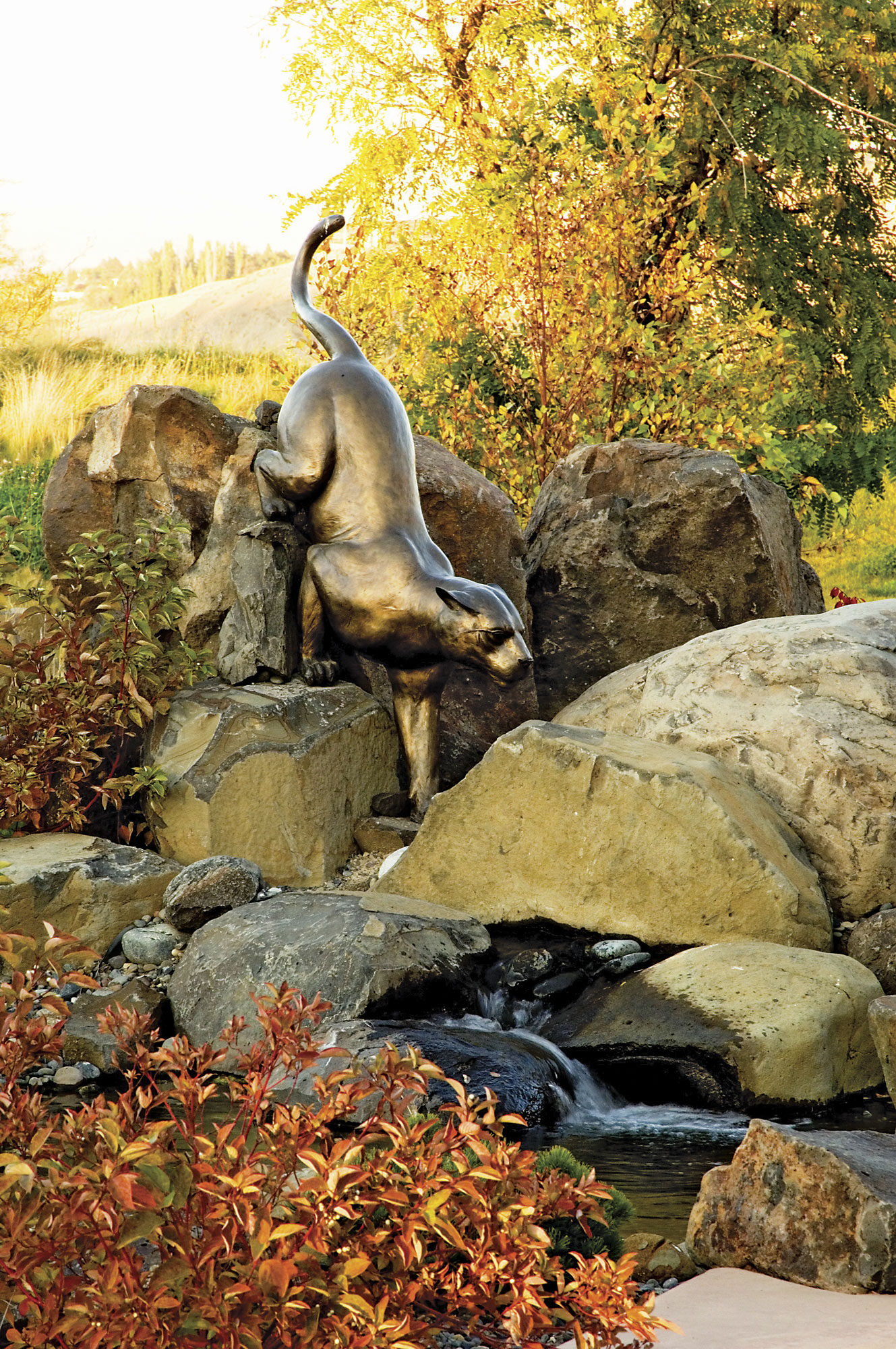

Doubtless, patrons of the exclusive Cherry Creek Shopping Center in Denver can identify the outsize animals in The Track, a bronze within footsteps of Saks Fifth Avenue shaped by renowned sculptor Kenneth Bunn. The Track, installed in 1993, is a visual narrative that captures the incipient alarm in a mountain lioness and cubs encountering the imprint of a male mountain lion.

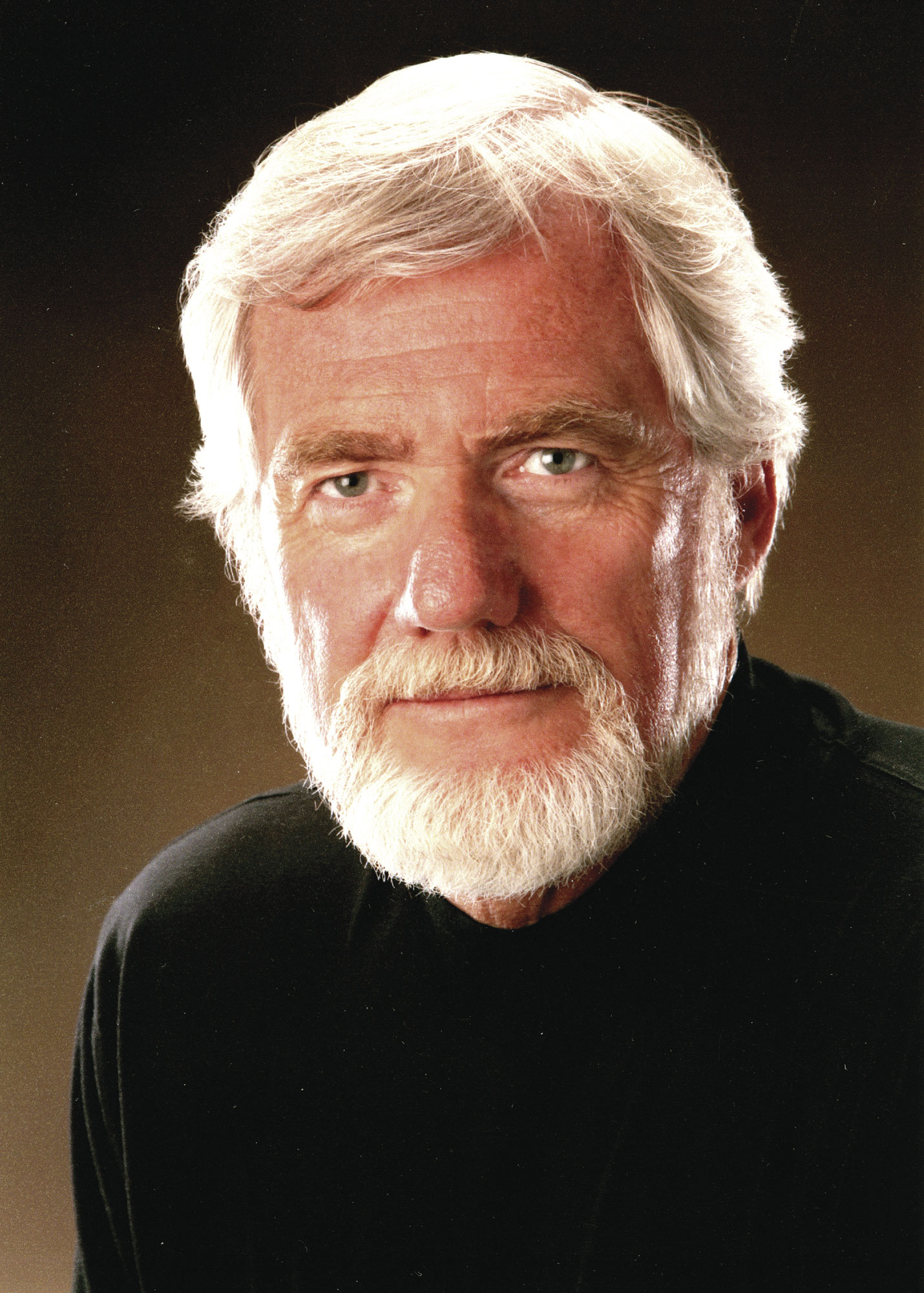

The Colorado-based Bunn, whose work is in the permanent collections of such venerable institutions as the Denver Art Museum and the Columbus Museum of Art, points to an equalizing mechanism that underpins masterworks. “One of the factors common to all great art is, people don’t have to ask what it is,” he says. Bunn, whose career has spanned more than 30 years and whose honors include election to the prestigious National Academy of Design and National Sculpture Society, received a string of commissions beginning in the early 1990s for landscape-scale works. Today, Bunn’s interpretative pieces, an assortment of such animals as antelope, polar bears and cougars leaping, swimming and springing to life, anchor everything from bank buildings to college campuses.

Modern-day monumental bronzes in public places echo a tradition in sculpture in the United States that stretches from the late 19th to early 20th centuries, when leading American animaliers such as Edward Kemeys and Alexander Phimister Proctor were producing massive wildlifes celebrating the nation’s romance with the West, enduring symbol of all that is untamed.

The meteoric rise of animal sculpture during that 25-year period beginning just before the turn of the 20th century served as a kind of flourish to the final days of the Western frontier and an acknowledgement of the advent of industrialization, says Peter Hassrick, director of the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum. Proctor’s animals abut bridges and stand before buildings as artistic metaphors for an era that ushered in the rise of entrepreneurs like Henry Clay Frick. And, by association, those captains of industry appropriated the characteristics of the animals in the sculptures they commissioned. Proctor’s pair of lions that guard the Frick Building in Pittsburgh “symbolize Frick and his command over the capitalist enterprises of America,” Hassrick says.

Swedish-born sculptor Kent Ullberg’s monumental wildlifes grace the globe, from bronze sailfish leaping before the bay in his hometown of Corpus Christi, Texas, to a great blue heron shaped in stainless steel on bronze at a municipal art museum in Luxembourg. Ullberg, whose wildlifes have garnered such honors as the National Academy of Design’s Barnett Prize for sculpture and the Prix de West Purchase Award, says society’s heightened appreciation for the natural world has set the stage for animals to assume primacy as subjects of art. “At no time in history until recently have wildlife — animals — been considered important enough to be honored on their own,” says Ullberg, the 1996 winner of the Rungius Medal from the National Museum of Wildlife Art. “Animals have appeared in art but only as symbolism, as adjacent to man.”

Where ancient peoples worshipped the divine, assuming the form and attributes of animals, contemporary culture at large is not seeking a reflection of its own image in the environment. “For the first time, we are representing the animal as itself, with some intrinsic value,” Ullberg says. “Our society has begun to see animals as a precious part of our environment, our world, just as worthy of being honored and celebrated for themselves as kings or conquerors.”

At a time when revitalizing the aesthetics and economics of dying downtowns has renewed interest and activity in everyday spaces and during a period when a percentage of funding for public construction and renovation projects must be earmarked for art, the age-old ethos of American landscape architecture — that the hearts of cities should beat in tandem with beauty — has gained fresh currency.

The nine mustangs stampeding across the square in Las Colinas is a textbook example of the recent move toward dramatic artistic statements in public spaces using the landscape as a palette, says Utah State University’s Timmons. It is a practice ushered in by such giants of landscape architecture as Lawrence Halprin, and it represents a shift from the longstanding practice of bringing the country into the city, or pastoral places into urban areas, a motif that drove the design of Central Park and embodied its designer, Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of American landscape architecture.

Ullberg’s just-completed opus is a sculpture of Canada geese and bison, Spirit of Nebraska’s Wilderness, that stretches across six blocks in downtown Omaha. The monumental work — part of a major redevelopment underwritten by the First National Bank of Omaha — incorporates elements of its urban expanse, with geese atop traffic lights and bison barreling through planters, symbolizing the city’s stake in the future even as the animals represent its debt to the past. The piece, marrying bronze and stainless steel as the wildlife moves into a contemporary context, exhibits dynamism equal to the fabled mustangs and, similarly, is a masterwork in a master-designed setting (both projects benefited from the genius of the late James Reeves).

Steve Boody is an arbiter of taste for major corporations, assembling art collections that provide paintings in the boardroom and sculptures in commercial centers. The president of the St. Louis-based Boody Fine Arts, the firm hired by First National Bank of Omaha to bring its art aspirations to fruition, likens the pattern in the United States of adorning landscapes with art to the European practice in place centuries ago. “There’s a tremendous amount of public awareness and acceptance of the theory that works of art in the environment affect the psyche of the individual — and, collectively, society — in a positive sense,” says Boody.

In a sign that the times are right for a return to the center of cities where art is on exhibit, Boody’s work with the private sector gave birth in 2004 to Public Art and Practice, a companion company that crafts master art plans for communities, park systems, universities and riverfronts. The underlying principle is, if you install it, they will come. “There is a new understanding that major works of art are instrumental in attracting people,” says Boody.

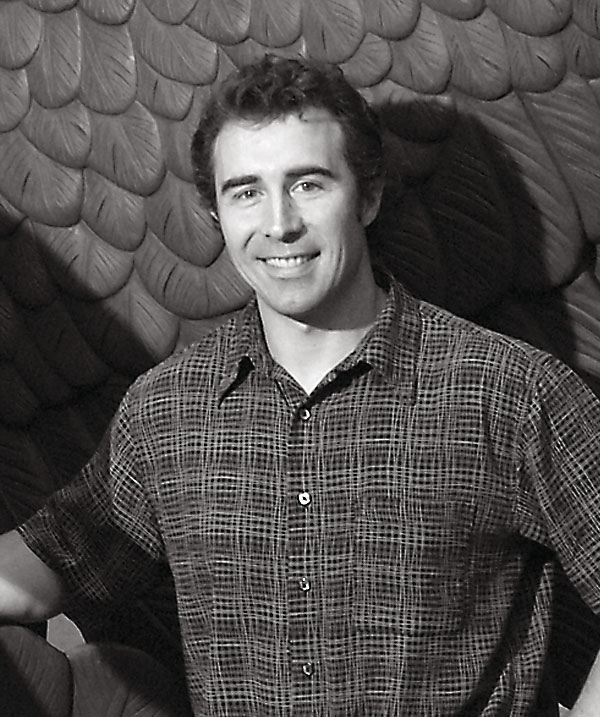

Acclaimed sculptor Tim Shinabarger is not satisfied to reproduce images of nature without experiencing them firsthand. Shinabarger routinely bids adieu to his mountain-view studio west of Billings, Montana, to trek through the wilds in search of the animals and the environs, seeking inspiration. “I think that this love for the wilderness is where my artwork comes from,” he says.

In the 15 years since Shinabarger began devoting himself full time to his art, he has gained the respect of his peers and placement at prestigious exhibitions. He is the recipient of some of the highest honors in sculpture circles, including the Louis Bennett Prize from the National Sculpture Society, and his bronzes have been added to the permanent collections of such institutions as the Museum of the American West at the Autry National Center. In the fall, Shinabarger’s monument-size masterpiece, Black Timber Bugler, was installed outside the National Museum of Wildlife Art against the backdrop of Wyoming’s Teton Range.

Shinabarger says his hope for publicly placed pieces is that they will instill in observers the same sense of awe and appreciation he feels for the natural world. “I hope they create an interest in the art and the wildlife and the sense that these things are worth preserving,” he says.

Idaho-based McNeil Development underscored the appeal of art in 2005 when it commissioned sculptor Vic Payne to shape two outsize eagles — one with a wingspan of 22 feet — to arc above a towering rock formation-cum-fountain that flows in the embrace of a sleek commercial complex in Idaho Falls. Hardly an afternoon passes that has not heralded the arrival of camera-bearing citizens who stand in the shadow of the great birds, craning their necks — and lenses — skyward.

Lately, the Cody, Wyoming, sculptor has been feeling the pain of success. Cabela’s, the outdoor retailer, has repeatedly recruited Payne to produce monumental bronzes, and he is frequently tapped by municipalities to shape figurative works that commemorate the Old West’s equally outsize personalities. Payne says sculpture is a problem that finds solutions, with deadlines as the occasional limitation to artistic license. “The general rule is, the more time a company gives an artist to create a piece, the better it will be,” he says.

The same principle is in play with Payne’s sculptures, which are imbued with an ever-evolving style. His philosophy about adding art to public spaces echoes the ethic behind Olmsted’s push to infuse parks with the picturesque. “It makes me feel good to know my bronzes are out there where people from all walks of life can enjoy them,” says Payne.

Buyers of upscale homes and offices offered by Veritas Investment Company in the Northwest tend to treasure the outsize bronze animals fashioned by Oregon-based sculptor Rip Caswell. It was not an afterthought that prompted Veritas owner Neil Nedelisky to commission Caswell to produce a 14-foot bald eagle, Guardian Spirit, in the act of alighting and to install the statue at the entryway of Eagle Landing, the company’s golf course community near Portland. Since 1994, Nedelisky has declined to plan a development without art assuming center stage. “Bronzes have a permanence and character you cannot get any other way,” he says.

Caswell’s work is on public display throughout the West, with the sleek lines of larger-than-life cougars taking shape before buildings in Vancouver, Washington, and in the scenic stretch that is Hell’s Gate State Park in Idaho. “I think what we are going to see more of is people trying to build a retreat, an inspiring place to live and work, right where they are,” says Caswell. “I guess what I do is provide little windows to nature.”

Three decades ago, Bunn devoted himself to art alone with no guarantees he would rise to prominence in his profession. “Sculpture is not a get-rich-quick occupation,” he says wryly. “But there is a fork in the road where you have to make a decision.” For Bunn and the wildlife sculptors who have followed him, it is an article of faith that while art movements come and go, the drive to shape works that celebrate nature is as affirming as love and equally uncertain. “I’ve learned all I can about my subject only to learn that there is no end,” says Bunn. “You can never really say you know all that you must.”

- “Adventure Bound” – Kenneth Bunn, bronze, 9’6 x 6 x 17’8 feet. Image courtesy of Gerald Peters Gallery.

- “Spirit of Nebraska’s Wilderness” – Kent Ullberg, bronze, Omaha, Nebraska. Image courtesy of artist.

- “Black Timber Bugler” – Tim Shinabarger, bronze. Image courtesy of artist.

- “The Protector” – Vic Payne, bronze. Image courtesy of artist. Finished in August, 2006, The Protector’s largest eagle has a wingspan of 22 feet.

- Kenneth Bunn

- “Wind in the Sail” – Kent Ullberg, bronze sculpture with red granite base. Image courtesy of artist. This 23-foot sculpture, located on the bay front in Corpus Christi, Texas, was commissioned in 1983 by the Corpus Christi-Caller Times to celebrate their 150th anniversary.

- Kent Ullberg

- Tim Shinabarger

- “Sik Sik Shell Game” – Tim Shinabarger, bronze. Image courtesy of artist.

- Vic Payne

- “Another Year to Grow” – Vic Payne, bronze, 8’6” x 18’6” x 6 feet. Image courtesy of artist.

- “Guardian Spirit” – Rip Caswell, bronze. Image courtesy of artist. With a wingspan of 14 feet, this 2003 bronze sculpture weighs 2,500 pounds.

- “Cougar” – Rip Caswell, bronze, 6’6 x 20 x 32 inches. Image courtesy of artist.

- Rip Caswell

No Comments