01 Apr Perspective: Ernest "Darcy" Chiriack

There is a reason Ernest Chiriacka’s name isn’t a familiar one amidst lineups of leading Western artists. It isn’t that he wasn’t trained at the best art schools in America: He studied at the venerable Art Students League and at the equally prestigious National Academy of Design. For four years he studied under Harvey Dunn, a protégé of Howard Pyle, at the Grand Central School of Art. As a boy, Chiriacka drew with anything he could find: charcoal from the fire, pieces of sheet rock that he could use like chalk on sidewalks. By the time he was a teenager, Chiriacka was known as the “Rembrandt of Third Avenue.”

Fast forward nearly a century to his death in 2010. A resurging interest in his fine art is due, in part, to the accessibility that collectors now have to his estate. For the first time in 27 years, Ernest’s daughter, Athene Westergaard, has unveiled paintings and illustrations of her father’s life, showing them in her 3,000-square-foot, museum-like Casweck Galleries in Santa Fe. “I feel privileged and honored to be exhibiting my father’s work to the public,” she says. “This year would have been his 100th birthday. I know he would be pleased to have his work offered to the public and he would also be pleased to be honored for his oil paintings being exhibited in museums Resting Buffalo program, something like “Downton Abbey.”

He was honored many times for his illustrations and pulp fiction paintings and was even on The Jack Paar Show when he was creating his pin-ups for Esquire. Showing his fine-art paintings is the fulfillment of his dream. He and I had always planned to show his art in New Mexico and had worked on it for seven years before he died.”

It’s almost as if with his death, Ernest Chiriacka was born once more into the art world he loved.

Born Anastassios Kyriakakos in New York City on

May 11, 1913, a son of Greek immigrants, Ernest Chiriacka is the transliterated English equivalent of his given name. The familiar form of the name Anastassios is “Tassi,” which sounds like the English name “Darcy” and is what the artist was called by friends and family.

Having lived through the Great Depression and World War II, Chiriacka’s life could be told today in a dramatic PBS romanticized in a series of pulp fiction novels with seductive covers suggesting intrigue and mystery. Or in the 1950s, his life could have been popularized in any of America’s well-known magazines of the time: The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Esquire or Argosy.

Except Ernest Chiriacka, the artist, was creating his life during the 1930s by painting pulp fiction covers under assumed names, a cloak-and-dagger act to hide his identity until he could break into the big time of “slicks” — America’s glossy family-oriented magazines.

In the America of the 1940s and ’50s, illustrators were in high demand to fuel the fantasies of readers who lived from month to month, clinging to the latest adventure of their hero portrayed on glossy paper. Paintings of live action adventurers popped off the pages and into the imaginations of readers, who were not yet inundated with television. Ernest Chiriacka created many of these scenes, working day and night to supply a multitude of maga-ACheyenneBride ed the beauties, all 12 each year. Author zines that printed his paintings on their pages: The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Esquire, Argosy and more.

Having attained his dream of moving from painting for the pulps to illustrating slicks, Chiriacka once again used his guile, painting under different names, this time due to non-compete clauses with publishers. While he was successful in selling his illustrations, the pseudonyms relegated Chiriacka to relative obscurity: Although he wanted to have a recognized name like Norman Rockwell, Chiriacka, in fact, had too many names.

Chiriacka’s style of work was highly sought after. He painted with what author David Saunders, who interviewed Chiriacka at his New York estate, described as “ … a hand-some style of Abbreviated Realism to create convincing illusions … this style was perfected by John Singer Sargent, who premixed each stroke from his infinitely malleable colors of oil paints, while Chiriacka simply used flat colors from jars of tempera paints, but he locked those planes into a suggested depth by the bravura of his drawing strength.”

Chiriacka’s work became more popular in the early 1950s when he was asked to paint two pin-ups for Esquire’s calendar. For five years, from 1952 to 1957, Chiriacka paint-Saunders says, “His sultry women have the dignity and proportions of a classic statue of Aphrodite.” Daughter Athene reveals, “He loved painting beautiful women, although mother always reminded him when the models showed up that ‘he could look, but he couldn’t touch.’ He used five different women to create one, he would use the best assets of each — the legs of one, the face of another to create his calendar beauties.”

Ernest Chiriacka had become wealthy — even buying an estate in Montauk, New York — but he had sacrificed his name for the sake of employment. It was the 1960s when, at last, Chiriacka began his career as a fine artist, showing his work under his own name at Kennedy Galleries and Grand Central Galleries in New York City. Daughter Athene speaks of this time, “He was very proud that they were selling his paintings; they were almost flying off the walls.”

Using oil on canvas, Chiriacka painted subjects that had fascinated him since childhood: Indians and the West. From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, Ernest and his wife and their pet bird would take road tours for months, to the West and the Southwest, to New Mexico and Arizona, to Colorado and the Dakotas, visiting reservations and doing research. He became fascinated with Lewis and Clark, and in 1973 the Battle of Wounded Knee deeply touched him.

In addition to the New York galleries, his art was popular in Chicago at the Mongerson-Wunderlich Galleries and in other galleries from Florida to Wyoming. “My mother was his manager, choosing to be ‘Miss Darcy, who knew the artist,’ never revealing that she was his wife. She was very instrumental in getting his art into the galleries, but she didn’t like him to go to the openings,” relates Athene.

Chiriacka continued to travel, even to Europe, sketching and painting, spending time in Greece and with his daughter and grandchildren, who lived in Belgium. In 1961 he started sculpting, creating more than 20 different pieces, some in bronze and some, one-of-a-kind. Joel Meisner and Company cast his fine-art bronzes.

In 1987, a tiny bite from a deer tick completely disabled him. Lyme disease, as it is now known, was not in the vernacular of medical professionals, nor was there a cure. Unable to paint, his wife gathered all of his paintings that were in galleries back into his studio, thinking he would never paint again.

Eventually, Chiriacka did recover and begin to paint again, but as his daughter, Athene, explains, “Once you have had a close escape, you begin to value life in a different way. He didn’t wish to have to meet deadlines anymore.”

Fortunately, Chiriacka’s work is collected by museums for the public to view. The Phippen Museum in Prescott, Arizona, is featuring two of his works in an exhibit titled Early West Storytellers, on view through July 7, 2013. Even though Chiriacka is less well known, the museum’s executive director, Kim Villalpando, says, “We are proud to exhibit the fine artworks of Ernest Chiriacka, whose devotion for the West is apparent in his paintings. His work, along with works by Ken Riley, Bill Moyers, John Coleman, Gerry Metz and Russell Houston, tell great stories about the early West.”

Crossing a Sea of Grass and A Cheyenne Bride, the two Chiriacka paintings in the exhibit, tell their stories with passion and obvious admiration, the way Chiriacka did in all of his paintings, whether they were pulp fiction novel covers, for “slick” magazines or fine art.

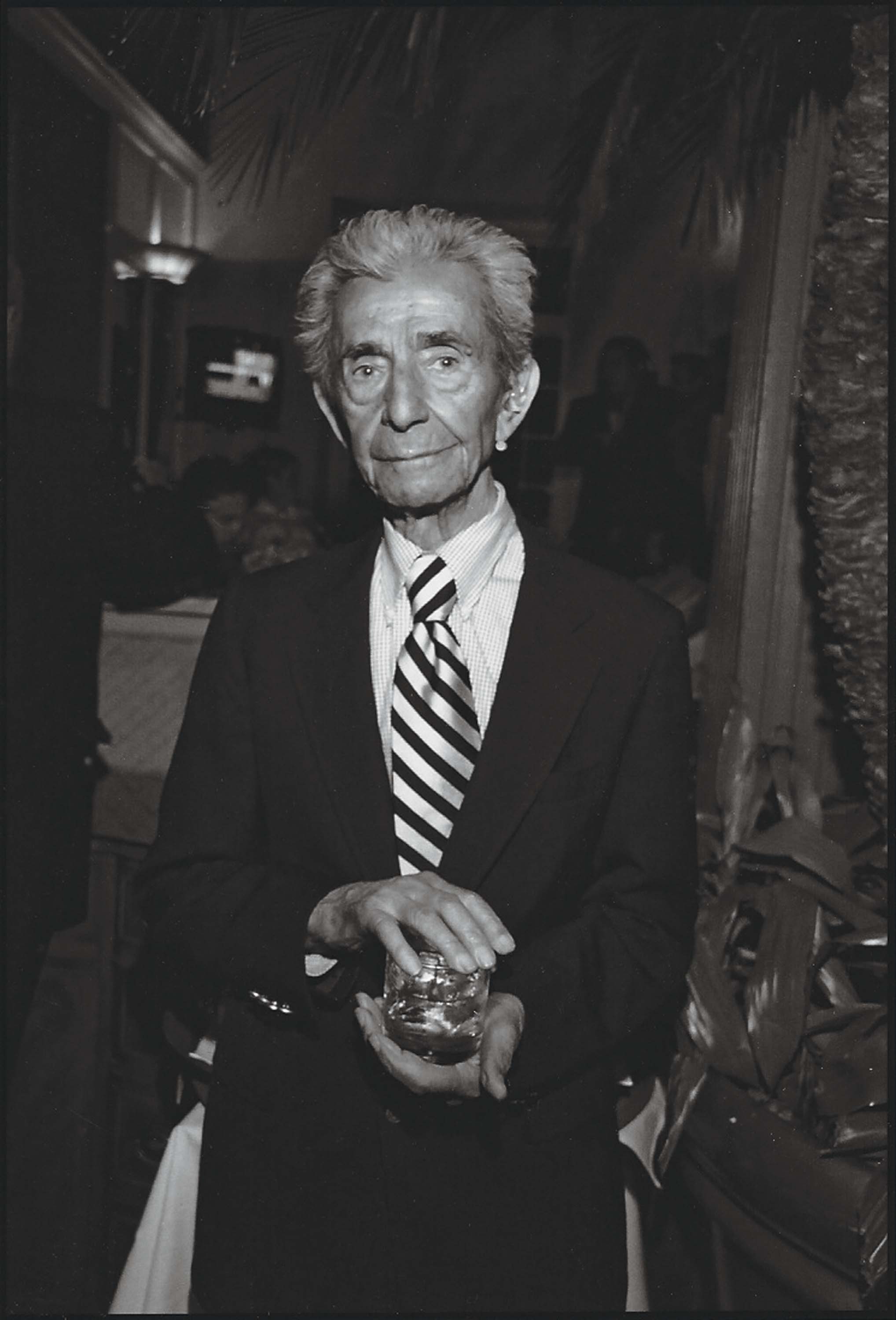

- Ernest “Darcy” Chiriacka, 2002

- “Resting Buffalo” | Oil on Board | 20 x 24 inches | c. 1970

- “The Red Package” | Oil on Board | 20 x 24 inches | c.1970

- “Crossing the Sea of Grass” | Oil | 48 x 35 inches | 1976

No Comments