12 Jul Pushing the Limit

TRAILBLAZER. ICONOCLAST. OUTLAW. So Antoine Predock has been hailed throughout his illustrious 52-year career. A charismatic risk-taker whose work joins the precise mind of an architect with the soul of a poet, Predock, 83, has, indeed, blazed trails of uncommon genius across the landscape of contemporary architecture.

In Santa Fe, a corridor in the Shadow House features a steel trellis that both protects the home from the midday sun and allows for a dramatic inter- play of light.

In an outdoor courtyard at the Shadow House, water rushes over ancient Chinese granite in a “river fountain” that reflects the sunlight and creates a magical interplay of light and sound throughout the interior. Photos: Daniel Nadelbach.

Predock’s deep reverence for the “spirit of the land” infuses his place-inspired buildings, noted for their expressive complexity and functional elegance. Based in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with additional studios in Los Angeles and Taiwan, Predock pioneered a Southwestern-influenced Modernism, which he has expanded and adapted in more than 100 international large-scale commissions, ranging from private residences, museums, resorts, and entertainment centers to sports complexes, civic structures, and educational and research facilities.

The kitchen in the Shadow House, with its cast-concrete floor, is distinguished by a copper chainmail curtain (left) that modulates the flow of natural light.

For his impressive body of work, Predock received a gold medal in 2006 from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) — formerly awarded to such visionaries as Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn, the two architects he most admires. He also garnered a Rome Prize and a Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt lifetime achievement award, among other distinctions.

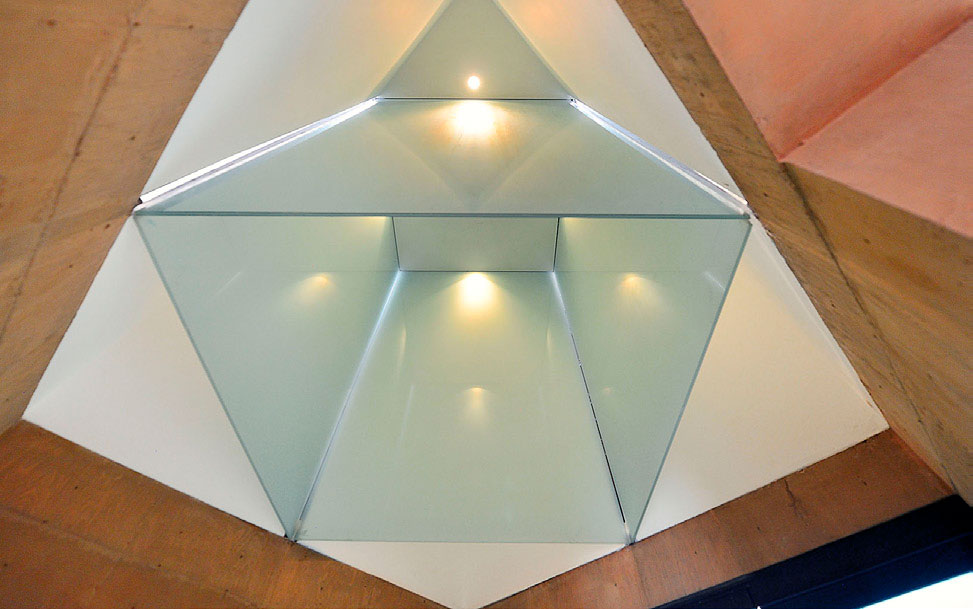

A cast-concrete tower with a glass prism filters light into the foyer of the Shadow House.

A steel trellis opens into the living and dining space of the Shadow House, with a maple ceiling and floor. An oversized cast-in-place concrete fireplace anchors the living room.

Predock’s self-described “portable regionalism” is rooted in his ongoing love affair with the American West, where he has lived most of his life.

“New Mexico is my spiritual home,” says Predock, who was born in Lebanon, Missouri, to an engineer father and a mother who read poetry to him. “The mystical quality of land and sky, the sense of deep geologic time here, it all took hold of me. New Mexico taught me how to pay attention to site specificity, how to be an architect. I bring this spirit of place to everything I create.”

The Sage House in Taos, New Mexico, was designed in an arc configuration with sleek, modernist lines and offers sweeping views of the dramatic high-desert landscape.

Predock began studying engineering at the University of New Mexico (UNM) but found it wasn’t a fit for his poetic soul. Encouraged by UNM architecture professor Don Schlegel, he moved to New York and received his architecture degree from Columbia University in 1962.

Designed for a renowned local chef, the Sage House has a restaurant-quality kitchen and spaces for large social events. The maple and steel staircase leads to an upstairs music room, while a central courtyard opens to the landscape for warm-weather parties. Photos: Daniel Nadelbach.

But New Mexico called him back. The desert, with its vast open spaces, dazzling light, and elemental forces, has inspired his architecture as much as his love of travel, art, literature, and what he calls “kinetic” pursuits. Predock, who studied painting with Elaine de Kooning and modern dance as a student in New York, recounts some of his free-spirited adventures, such as motorcycling through Europe after college and skiing on the roof of the condominium complex he designed at Taos Ski Valley.

One of Predock’s best-known works is the La Luz townhouse community outside of Albuquerque. His first project, designed in 1967, gained international acclaim for its striking minimalist adobe interpretation of the pueblo dwellings of the region’s indigenous peoples. Predock went on to leave his mark in The Land of Enchantment with 30 other projects, including two signature private residences.

Northwestern University’s College of Journalism and Communication at Education City in Qatar is an abstract expression of the rugged local landscape. The more than 500,000-square-foot structure features a high-tech screen that broadcasts student activities and videos. Thickly textured limestone walls protect inner courtyards from the harsh desert climate.

The Sage House in Taos (2008), designed for a renowned local chef, is distinguished by its sweeping arc configuration with a series of spaces organized around a central courtyard, offering dramatic views of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Overlooking the Jemez Mountains, Shadow House in Santa Fe (2003) embodies the high desert’s “ineffable space and introspective solace,” according to Predock. Its spare, geometric design includes a central tilted water court made of ancient Chinese granite, creating a magical interplay of light and sound.

Predock’s other masterpieces include the Nelson Fine Arts Center at Arizona State University in Tempe (1990), evoking a procession through the shifting moods of the Sonoran desert; the Venice House, an iconic Modernist beach house in Venice, California (1991); and a $285 million stadium for the San Diego Padres (2006), which imaginatively reinvents the ballpark as a garden with stepped terraces and open views.

Notable among his more recent creations are a lakefront community and performing arts center built in 2014 in Chengdu, China, that was inspired by regional culture and the Sichuan landscape, and a state-of-the-art media and communications building on Northwestern University’s campus in Education City, Qatar (2017), said to have the most technically advanced production facilities available to students anywhere in the world.

A square-patterned steel trellis, extending from the ceiling to one wall in a corridor at Northwestern University’s campus in Qatar, casts an enchanting light pattern on the floor and opposite wall. Interweaving spaces throughout the building encourage dialogue, interaction, and collaboration. Photos courtesy of Antoine Predock.

For Predock, though, one project stands out among others. He considers the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg (2014) — a sublime meditation on the commonality of humankind — to be the culmination of his career. The museum’s glass Tower of Hope rises like a mountain from a central great hall, called the Garden of Contemplation, which is carved into the land with limestone “roots” and enveloped by a glass, cloud-like abstraction of dove wings, symbolically integrating heaven and earth. An image of the building graces Canada’s $10 bill and one of its postage stamps.

The Nelson Fine Arts Center at Arizona State University in Tempe evokes a processional journey through the Sonoran desert with a series of galleries, courtyards, terraces, and balconies offering multiple “trails” of expe- rience throughout the building. The concrete and steel tower projects images of artworks onto the opposite fly-tower. Photo: Tim Hursley.

All of Predock’s contextual, expansive spaces weave together past and present in an intimate dance with the surrounding landscape and its accumulated history. Yet Predock’s buildings — which combine simple, natural materials like stone, glass, and concrete with sleek metals and high-tech innovations — defy a particular style. They are at once sensual and cosmic, boldly imagined and rigorously constructed, emanating the catholic tastes and mutability of the architect himself. Predock is as enamored by the gravitas of history and ancient forms, like pyramids and obelisks, as he is by science fiction movies, old motels, and neon glitz. All of these eclectic influences find their way into his work.

A motorcycle enthusiast and collector, Predock enjoys a recent ride on his electric “Zero” motorcycle in the Santa Monica Mountains of California. Photo courtesy of Antoine Predock.

“Architecture is a ride, a total adventure for me and my clients,” he says. “There has to be a fusion of form, poetic qualities, and the essence of place while solving a functional problem. I see my work as a multi-sensory, choreographed experience, a procession through time and space that tells an episodic story.”

Predock says his architecture “embodies cultural memory,” likening it to a “highway roadcut,” a sectional diagram of the earth that reveals strata of ancient geologic formations overlaid with the intrusions of culture over time. His design process unfolds with meticulous research, expressed in drawings, clay models, and collages that distill his original creative impulse.

“Antoine takes the design process to a whole new level and remains fully engaged until the building is complete,” says John Quale, professor and chair of the architecture department at UNM. “His particular genius is visualizing buildings in a variety of ways and making sure they align with the idea he has in his mind. His curiosity knows no bounds, and his passion for excellence drives every one of his projects.”

Antoine Predock stands before several clay models of his buildings at the Predock Center for Design and Research.

Predock designed the School of Architecture and Planning at UNM, to which he has donated his downtown Albuquerque former residence and studio, where he lived and worked for 50 years. Now called the Predock Center for Design and Research, the 10,000-square-foot space is scheduled to open within the next year. It will include a workshop and design studio for graduating architecture students, as well as gallery spaces displaying architectural models, collages, copies of drawings, and photographs from Predock’s archives (housed at the UNM Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections), along with a host of personal memorabilia and two vintage motorcycles from his collection.

“This house was a hive for the arts,” says Predock, who is married to sculptor Constance DeJong. “My two sons grew up here, surrounded by modern art and design, dance workshops, and performances. There was always something fun and exciting going on. When my wife asked what I was going to do with all my ‘stuff,’ it felt natural to make this gift to the University of New Mexico, where my passion for architecture began.”

As with all great artists, Predock’s life and work are inseparable, and this spirited octogenarian has no plans to slow down. He is currently working on a private residence in Albuquerque’s north Rio Grande Valley and a multiple-dwelling enclave in Costa Rica, where each house “has a story to tell about the site,” he says.

Predock currently lives in west Albuquerque just off historic Route 66 in a high-mesa, modernist house with walls of windows, which he designed as “an observatory of nature.” His motorcycle collection is a focal point of inspiration in his adjacent studio offices, where he employs six designers.

An architectural model of the American Heritage Center and Art Museum at the University of Wyoming, Laramie, is sur- rounded by other models of Predock’s projects at the new Predock Center for Design and Research, located at the architect’s former residence and studio in downtown Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photos: Daniel Nadelbach.

Reflecting on his exhilarating ride to the peak of his profession, Predock says he is ultimately on a singular architectural mission.

“I want my work to touch people by bypassing their head for their heart. We all have an inner life. Architecture is not only about intellectual and pragmatic concerns. It has layers of meaning and power, and that is what distinguishes great work from just getting the job done.”

No Comments