16 Jul Collecting Pueblo Pottery

IN THE PANTHEON OF COLLECTIBLE ITEMS ON DISPLAY at Indian Market in Santa Fe every August, pueblo pottery is perhaps the most coveted. Ranging in technique and design, pots, jars, urns, and plates tell a story of traditional craftsmanship, often brought into the 21st century by modern potters.

Maria & Popovi Da | “San Ildefonso Pottery” | 12.5 inches in diameter | 1960 | Blue Rain Gallery

Maria & Popovi Da | “San Ildefonso Pottery” | 7.75 x 9 inches | 1959 | Blue Rain Gallery

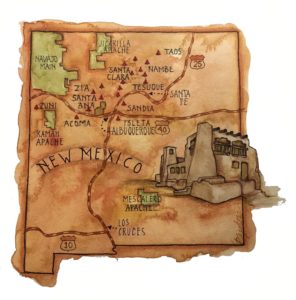

Primarily making their homes in the Four Corners region, pueblo tribes established dwellings and trade centers similar to those located at Chaco Canyon in Northwestern New Mexico and Mesa Verde in Southwestern Colorado. Today, many of the 19 pueblos in New Mexico bring variations and techniques in technology, form, and decorative style to pottery. Cultural traditions, religious beliefs, and family customs also play a part in the formation of clay.

In a documentary shown at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, artist Maria Martinez [1887–1980] demonstrates the spreading of sacred blue cornmeal prior to extracting the black clay used in pottery by the San Ildefonso Pueblo. “We put the corn on the clay so the great spirit will help us and give us our strength and good pottery,” Martinez says.

Tony Da | Sculpted Redware Turtle | 8 x 9.5 x 7 inches | 1975 | Blue Rain Gallery

Tony Da | Sculpted Redware Turtle | 8 x 9.5 x 7 inches | 1975 | Blue Rain Gallery

The Museum of Indian Arts has an impressive collection of historical pots dating to prehistoric times when the Native peoples of the Southwest first started experimenting with clays, slips, paints, and textures to create regional styles and the unique traditions of each pueblo.

“It’s a personal learning process,” says Andrea Fisher, of Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery, an American Indian pottery gallery in Santa Fe. “It’s a visualization, a whole narrative. Some stories are more important than the piece. That information can get lost, and it is so valuable.”

Virgil Ortiz | “Revolt 1680/2180” (Storage Jar) | 16.5 x 11.5 x 11.5 inches | Cochiti Red Clay, White and Red Clay Slip, Wild Spinach Plant (Black Paint)

Virgil Ortiz | “Squash Gourd” | 27 x 15 x 10 inches | Contemporary Clay, Velvet Under Glaze, Acrylic Paint

So, there are 19 pueblos in New Mexico alone, with artists creating both modern and historical pots, using differing techniques. When you visit Indian Market, you may be troubled to find the works of each pueblo are not displayed together. Not to mention that there are more than 1,500 vetted exhibitors set up every year.

Where to begin?

Denise Phetteplace, gallery director at Blue Rain Gallery, which has offered pueblo pottery for 25 years, advises collectors to look for both quality and innovation. “Buy the best you can afford and what appeals aesthetically. When you start a collection, you start out on a journey — a journey that never ends at one or two pieces.”

Fisher warns that it’s important to come armed with knowledge: “Do your homework and look, look, look,” she says. “Don’t be surprised by the prices. Pueblo pottery is the result of a longstanding tradition that is very labor intensive.”

The process of horizontal hand-coiled pottery dates back more than 2,000 years, and remarkably many of the same techniques are still used today. Clay is dug from the earth, cleaned by hand to assure there are no twigs, rocks, or leaves, then molded into form and fired outdoors in a mound of wood and manure.

“Cleaning the clay is the most important and time intensive part of the process,” says Fisher. “If the clay is not refined, it can explode or develop cracks. A really good potter only gets 80 percent of what they start out with. One air bubble or piece of grass can end a reputation.”

Jody Naranjo | “Fish Bowl” | Sgraffito-Carved Natural Clay with | Acrylic Paint | 3.75 x 7.75 inches | 2018 | Blue Rain Gallery

Jody Naranjo | “Fish Bowl” | Sgraffito-Carved Natural Clay with | Acrylic Paint | 3.75 x 7.75 inches | 2018 | Blue Rain Gallery

After a pot is formed and polished with a river stone, a design is applied to the surface with a blade of yucca grass specially prepared by scraping away the pulp, leaving only the natural fiber. The “paint” is most often clay slips made by combining clay and water.

While the process is time consuming and grueling, the market for these wares is much the same. Top potters hold to the old ways, but market demand has dictated an update caused by a search for perfection — a move from the traditional firing to the use of a kiln.

Jody Naranjo | “Butterfly Pot” | Hand-Coiled Sgraffito-Carved Natural Clay with Acrylic Paint | 6.25 x 5 inches | 2018 | Blue Rain Gallery

Acoma pottery, revered for a dramatic fine-line design painted in black over a white background, may come out of the fire with a haze of gray due to uneven heat occurring during traditional firing. Collectors rejected these clouds as imperfections, pushing Pueblo potters to use commercial kilns.

“Buyers are taken with the black-and-white designs they feel are so precious,” says Fisher. “If it is broken, if Mother Nature has had a hand in the design, they will reject it. Fire clouds are perceived as a mistake or flaw, but there are some collectors who buy pots with only fire clouds and no painted design.”

it is broken, if Mother Nature has had a hand in the design, they will reject it. Fire clouds are perceived as a mistake or flaw, but there are some collectors who buy pots with only fire clouds and no painted design.”

Blue Rain represents works from the early 1900s to present day. The gallery is one great place to start homework.

“The newer pieces illustrate how individual potters began to be recognized internationally for their work,” says Phetteplace. “We sell through all Jody Naranjo’s pieces so quickly. She is known for asymmetrical shapes and for her sgraffito. To me it’s like chalk on a blackboard; it gives me chills.”

Naranjo, a Tewa potter from the Santa Clara Pueblo, has won Best of Pottery at Indian Market and numerous other awards. Her work has been featured in books and museums.

Virgil Ortiz | “Untitled” | Natural Clay and Pigments | 11.5 x 9.5 x 3 inches | Blue Rain Gallery

“My pottery is made traditionally,” she says. “I dig my clay, polish with a stone, and pit-fire. My shapes and designs are contemporary. Part of it is my personality coming through the clay, and another reason is I love to experiment and play with new shapes and ideas. Asymmetrical shapes and a lighter, happier look at Native life is kind of my thing.”

Her sgraffito work on the surface of her pottery is partly how she designs. “My family is known for it,” she says. “My grandfather used a nail to etch pottery; I use an X-acto knife. You can get both very intricate designs or deep, defined lines using this process.”

At Indian Market, one can expect to see a variety of contemporary pieces, including hand-coiled figures of demons and devils with tattoo-like designs. Virgil Ortiz, whose work may be found not only at Blue Rain Gallery, but in museums nationwide, integrates cutting-edge imagery into traditionally realized work, winning multiple awards at Indian Market.

Adam & Santana Martinez | “San Ildefonso Pottery” | Natural Clay | 16.5 x 7.5 inches | 1988 Blue Rain Gallery

“I am inspired by modern design of all kinds, whether it is fashion, architecture, film, sculpture, or music,” says Ortiz. “These influences transform as I build my figurative clay works and also my surface designs. Luckily for me, historic Cochiti Pueblo figurative clayworks were based on social commentary, which leads me to a variety of subject matter for my pieces, yet keeps them under the traditional umbrella. Even if I do push beyond the limit in design and construction, I know it will challenge the up-and-coming potters to do the same.”

Ortiz’s mission is to not only revive the style and subjects created in the late 1800s, but also to continue to tell the story of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. Because the historical figurative work of the Cochiti Pueblo appears contemporary in design, it was a natural progression for him to take these influences and add his own interpretations.

“It is an exciting time to witness the birth of these artistic ideas in full force at Indian Market,” Ortiz says. “My traditional work will always be the heart and soul of everything I do. I am now entering into the world of high-fire contemporary ceramics — a new and exciting body of work I plan to unveil during this year’s market.”

Editors Note: The 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market takes place August 17 through 18.

No Comments