06 May Rendering: The Lay of the Land

“When Kate and Vera started the company, they deliberately gave it the name Arterra versus using their names,” says Gretchen Whittier, a partner at Arterra Landscape Architects. “The intention was that the company was going to be bigger than either of them.”

Arterra — a combination of the words art and terra (Latin for earth) — is an award-winning firm with offices in San Francisco and Healdsburg, California. It’s headed by Kate Stickley and Whittier, who became a full partner in 2016 after co-founder Vera Gates retired.

Both Stickley and Whittier grew up as though they were apprenticing to become landscape architects, though neither knew a thing about the profession.

- For the home Inspired by the Land, a metal arbor was designed to match the willow branches covering the patio in the main house. Photo: Vivian Johnson

- The fire pit, with its board-formed concrete footrest, provides a spot for viewing sunsets and extends the home’s footprint outdoors. Photos: Joe Fletcher

Stickley was raised in a new subdivision backing farmlands outside of Wilmington, Delaware. She spent her time climbing the framing of new houses, damming a backyard creek with stones, and cutting through briars with clippers. It wasn’t until a high school counselor asked her where her interests lay — the outdoors, but also art and design, although not fine art — that she learned of landscape architecture. Stickley ended up studying the profession at Michigan State University, where she says she received an education more practical than theoretical.

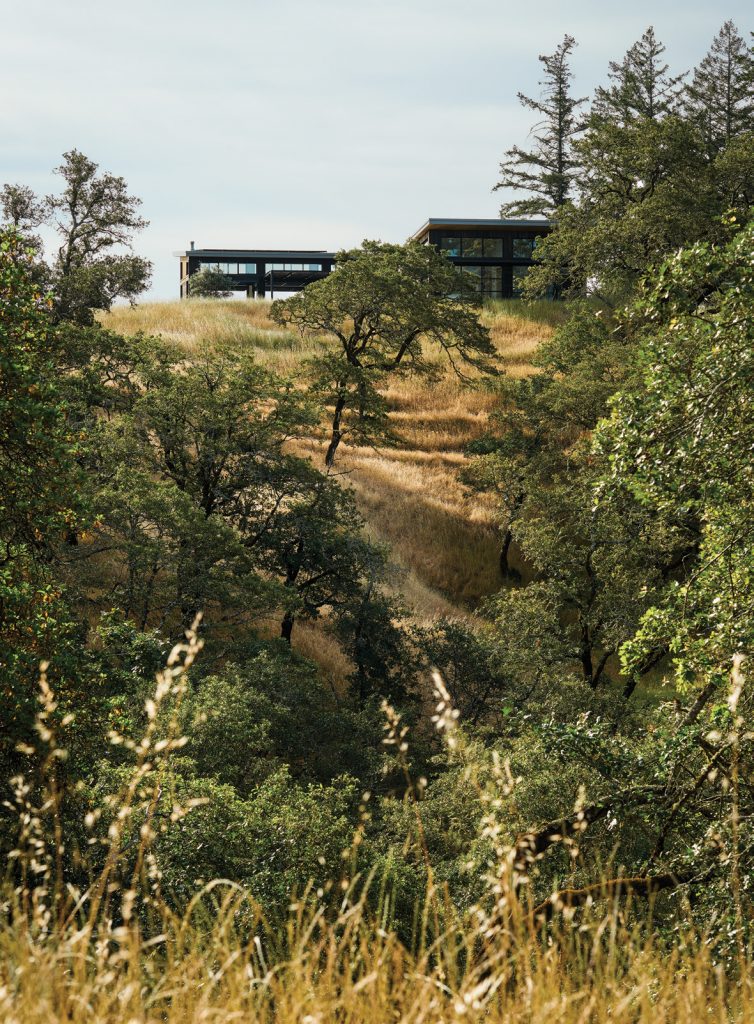

- The house is set on a promontory to take advantage of the views. The cedar siding evokes the colors of the surrounding hills.

- Native deer grass plantings decorate the landscape, while garage doors lift to erase any separation from nature. Photo: Joe Fletcher

Whittier, the child of a stonemason and an avid gardener, was raised in a 1785 farmhouse that was constantly being added onto or renovated. Looking back on visits to the neighbors’ homes, she says, “I realized I could visually track the exteriors, the stone walls, the types of stone used, the planting beds, the ponds, and all that, but I couldn’t tell you what was happening inside the houses.”

Whittier was working for design firms, but it wasn’t until she moved to San Francisco and took a drafting course that she discovered landscape architecture.

The pool is close to the house and sheltered from the wind. The decks are minimal, allowing the pool to nestle into the native grass. Photo: Caitlin Atkinson

When Stickley graduated from college, landscape architecture was a little-understood profession. “You’d get the question, ‘Oh, the rhododendron in my backyard isn’t doing so well, can you help me with that?’” she says, laughing. “No, go to your garden center.”

But today, people are more likely to understand that landscape architecture is far more complex than designing beautiful gardens and patios. “We design everything from the walls of a house out,” Stickley says. That can include grading, drainage, rainwater capture, recycling, and can even affect the positioning of a house on the site if Arterra is brought into a project early enough. An architect’s choice of interior tiles, for instance, might not be a good fit for exterior use, and in California, where indoor-outdoor living reigns, everyone wants the tiles to be continuous. “The best practice for getting the most out of your land is to assemble an interdisciplinary team before the project starts,” Stickley says, “getting the architects, the landscape architects, the civil engineer, and everyone on board from the beginning.”

Blackened-steel elements in the outdoor kitchen extend the feel of the dark cedar siding and add an element of fire safety. The metal and woven willow branch covering protects the area from the sun. Photo: Vivian Johnson

The firm’s goal is to fulfill the clients’ vision and enhance a structure’s architectural design. “We’re the people on the team who help ground that building,” Stickley says, “and give it meaning on the land, as well as to provide opportunities for people to get out and have a completely different experience outside of the perimeter of the house.”

Sustainability is a basic element of Arterra’s work, which can start as early as ensuring that the contractors keep their impact on the land as minimal as possible. Stickley explains that the aspects of Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) that define the gold standard today are things they had been doing for years.

At Inspired by the Land, the outdoor kitchen overlooks the pool. Photo: Joe Fletcher

“We look at a site holistically — how to deal with the grades, the drainage patterns, the existing vegetation, the topography, and how to make that feel as though the built environment has a seamless introduction into the natural environment,” she says.

Capturing rainwater is increasingly popular with ecology-conscious homeowners, but adding a sufficient number of tanks to capture rainwater for a large property can be impractical and prohibitively expensive. One solution is to combine rainwater capture with greywater recycling. These are the kinds of discussions Stickley and Whittier delight in having with their clients and design collaborators.

The entry to Stone House is nestled in a woodland of coast live oak. Mediterranean plants are mixed with those native to California for a water-wise palette. The concrete driveway blends into the sunken courtyard below.

After the devastating fires California experienced in 2019, both partners attended a fuel management workshop in the Santa Lucia Preserve with fire behavior specialists. Everyone agreed that over the next five years, regulations and requirements for new builds would be in flux between the state, counties, and local fire restrictions, many of which are currently contradictory. Then there are the insurance companies. “The fire codes have us jumping,” Whittier says dryly. In all of Arterra’s rural and semi-rural projects, access for first responders and enough room for large fire trucks to turn around must be included. The challenge is to design these driveways and turnarounds so that they seem like a natural part of the environment.

Porcelain tile extends from the great room onto the terrace for a seamless connection to the outdoors. The outdoor fireplace doubles as an anchor for the terrace and a privacy screen from the neighbors.

“We really advocate for our clients to talk with officials and insurance companies before they sign off on the design,” Stickley says. “That way, they’re assured of the coverage, and we can include and educate the insurers, so they don’t feel like they have to make a power move and have you pull out all the plants at the end. We lay out the driveway approach in an aesthetic and climate-conscious way, but we also use it as a fire-break.”

At Slot House, patio furniture and a red water wall reference the colorful plants — including kangaroo paw and poppies — on a dining patio. Photos: Adam Rouse

“We try to turn regulations into an opportunity,” Whittier adds. “If we’re required to handle all the water runoff on a site, we’ll turn it into a swale or a dry creek. And we’re used to using non-pyrophytic plantings.”

But some insurance companies don’t understand what practices are really effective versus what Stickley calls “overkill.” Regulations requiring a planting-free zone around a building aren’t going to do much good if the house has a shingle roof or wood siding. A house in the Dry Creek area outside Healdsburg, named Inspired by the Land, has grasses growing right up to its edge. The house was designed before the fires, but Stickley isn’t worried about it.

“Grasses aren’t the problem,” she explains. “The fuel in grass burns instantly; it doesn’t burn hot. It’s woody plant material — trees — that create embers that fly and have a sustained burn rather than a flash burn.”

The home’s living roof is visible from the second-floor bedrooms. The foliage changes color year-round, contrasting with the dark green shade of the woodland oaks below; succulents add to the visual interest.

Architects sometimes need education as well. Their goal is to take full advantage of the views, but the edge of a steep slope, for instance, is an extremely fire-prone spot. “There are studies that show if you put the building back 10 or 20 feet, it can increase the fire safety,” Stickley says, adding that Arterra also provides information on the exterior palette, for example, how an extended eave or cantilevered section should be without wood siding or lining. “Let’s look at a concrete base versus a wood deck on an upslope with terrible fire-prone tendencies,” she says.

The concrete and gravel entry at Taronga connects to the limestone, stucco, and corten steel siding. The guest house in the foreground is connected to the house by a breezeway.

Taronga is a house in California’s Santa Lucia Preserve where Arterra’s contributions to the design include a water feature at the front entrance and extending an interior wall out to the entryway on one side and through the terrace on the other. Their input also led to the placement of the garage below the guest wing, where the roof was then planted with beautiful grasses. They also suggested putting the pool in at a different angle from the house, which, Stickley says, “was a slight twist to the materials and the orientation, to make it feel more like a destination with its own spirit of place.”

A fountain creates a focal point for the entry sequence at the front door.

At the Slot House in Los Altos Hills, California, ornamental plantings were kept close to the home, then surrounded with native plants that blend with the park-like setting. Gravel pathways lead to discrete seating areas. Splashes of color include red poppies that bloom in spring and kangaroo paws that are colorful all summer. The dark green of the coast live oaks contrasts with blue-green and chartreuse plantings, westringia, blue chalk fenicia, and foxtail ferns, all of which provide interest year round.

The entertainment terrace overlooks an infinity-edge pool, with the pool house at the far end. Agave and native plants complement the oak trees. Photos: Holdren+Lietzke Architecture

“We got into this because we really like working with people,” Stickley says. “We pride ourselves on being excellent translators, on understanding the land and what our clients’ goals are. Then we take it to a level the clients haven’t thought of. Otherwise, they could just get a design-build firm or a garden designer or someone from their local nursery. I think we do a really good job of understanding a site’s natural systems, and we look for those special moments, the spiritual center of each property.”

No Comments