10 Mar Perspective: A Force of Nature

By the time Catharine Carter Critcher set off on her own for Taos, New Mexico in 1920, she was 52 and had been making her living from art for almost three decades. She had spent five years in Paris, started an art school there and another in Washington, D.C., and was a well-established portrait painter on the East Coast. What she experienced in the Southwest was new and fascinating to her. But unlike many artists in Taos at the time, including members of the Taos Society of Artists, she wasn’t interested in painting the grand, romantic narrative. She didn’t produce large canvases with mountains towering above Taos Pueblo’s ancient adobe structures or Pueblo men wrapped in colorful blankets.

Instead, she did what she had always done. She stood at her easel in front of an individual or small family group and painted the essence of her sitters as she perceived them.

By her fourth summer in Taos, she had become known to the Taos Society of Artists, and in a clear indication of their respect for her work, they unanimously voted her into the group as its only female member in 1924. It was an honor that pleased Critcher, who wrote to a friend that it was “nice to be the first and only woman in it. I am feeling very good about it.” Although she never lived full-time in Taos, maintaining her career in the East and returning to the Southwest each summer for 10 years, she remained a member of the Society until it disbanded in 1927.

Yet, Critcher has never received the level of recognition given to the group’s other members — among them Bert Phillips, Ernest Blumenschein, E. Irving Couse, Joseph Henry Sharp, and Oscar Berninghaus — in part because she was not a full-time resident and thus less integrated into the Taos Society’s activities.

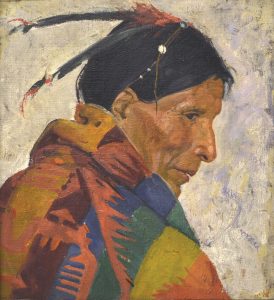

Indian Mystic | Oil on Canvas | 22 x 18 inches | Date Unknown | Courtesy of Sotheby’s

It’s an omission that sorely needs to be amended according to art historians, including Davison Packard Koenig, the executive director of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site in Taos. “She was a very talented, bold, confident, determined woman who buck[ed] the system to pursue her passion for art. I would love to see someone write the Catharine Critcher book — it’s a book waiting to be written,” Koenig says. Adds Susan Fisher, former executive director of the Taos Museum of Art at Fechin House (now executive director of the Mystic Museum of Art in Mystic, Connecticut), Critcher “must have been a force of nature.”

Born in 1868, just after the Civil War, Critcher grew up in an aristocratic family on an estate near Oak Grove, Virginia. She was the youngest of five children to parents Elizabeth Thomasia Kennon Critcher and Judge John Critcher, an officer in the Confederate States Army who was later elected to Congress. As a child, Critcher’s favorite activities included drawing and painting, and in her late teens, she persuaded her parents to allow her to study art in New York City. After a year at The Cooper Union, she moved to Washington, D.C., and enrolled in the Corcoran School of Art. Her main interest was portraiture, and she soon began receiving portrait commissions from prominent Virginia families. Over the course of her long career, she painted such figures as President Woodrow Wilson, General George Marshall, and Senator Harry F. Byrd.

Catherine Critcher in her studio, Taos, New Mexico | Gelatin Silver Print | 9.5 x 6.625 inches | Date Unknown | Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art, Neg. No. 20452

But Critcher’s passion for art went beyond formal portraiture. Aware of the stirrings of new art movements in Europe at the turn of the century, she traveled to Paris in 1904 to study at the Académie Julian. While her painting ability gained her admittance, her language skills lagged, making the experience difficult. So in 1905, with the assistance of two of her former instructors, she founded Cours Critcher (the Critcher Course), an English-language art school aimed at preparing students for French academic instruction. Meanwhile, her paintings were juried into the prestigious Paris Salon exhibition and she became president of the American Women Painters in Paris.

During her five years in France, she also earned money during summers by guiding European tours for Americans. As Fisher puts it, “She was very self-directed.” Just as importantly, while in Europe she absorbed the beginnings of Modernism. It was an influence that later emerged in her paintings in Taos, where she was free from the constraints of commission work.

Light Lightning | Oil | 17 x 15 inches | Date Unknown | Collection of the Brinton Museum, Gifted by Mr. Toy D. Savage, Jr.

After returning to America in 1909, Critcher taught at the Corcoran School of Art for 10 years. In 1924, she and sculptor Clara Hill opened the Critcher-Hill School in Washington D.C., which Critcher ran for almost two decades until turning full-time to painting. In a pivotal event around when she left the Corcoran, she heard about and visited an East Coast exhibition by the Taos Society of Artists. The Society was organized in 1915 primarily as a commercial initiative, promoting members’ art by arranging shows in other parts of the country. Impressed by the paintings and their subjects, Critcher set off for Taos in 1920.

This was during a time when few women traveled alone. The journey involved taking the train to Denver, the Chili Line narrow-gauge train to northern New Mexico, and then traveling overland to Taos, which included a steep hairpin descent into the Rio Grande Gorge, John Dunn’s ferry across the river, and then finally climbing up the east side to reach the village.

Upon her arrival, Critcher was immediately struck by what she considered a lovely and beneficial sense of remoteness and otherness. As she put it in a letter to a friend: “Taos is unlike any place God ever made, I believe, and therein is its charm and no place could be more conducive to work; there are models galore and no phones, the artists all live in these attractive, funny little adobe houses away from the world, food, foes, and friends.”

She set up a studio and began painting Pueblo people, including pottery-makers and other artisans, and family groups. As with virtually every painter who came to the Southwest, she saw her color palette brighten in response to the region’s clear light, abundant sunshine, and the hues of Navajo and Pueblo textiles and pottery.

Three Indian Women | Oil | 13.5 x 12.25 inches | Date Unknown | Collection of the Brinton Museum, Gifted by Mr. Toy D. Savage, Jr.

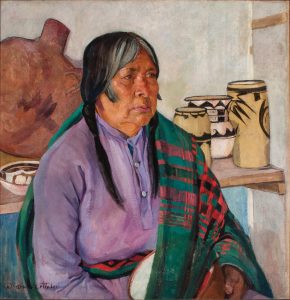

Her East Coast portraits tended to follow the conventions of the time, including a somber palette that Fisher describes as “the brown soup variety,” with sitters in dark clothes against a subdued formal backdrop. In New Mexico, the artist was finally liberated from convention or any expectation of a flattering likeness on the part of the paying client. Fisher expresses admiration, in particular, for Critcher’s authenticity and fearlessness in “painting people she has no way to understand and can’t communicate with, and yet she sees people, not stereotypes.” Christian Waguespack, the curator of 20th-century art at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, agrees, describing Critcher’s portraits as having “a strong interiority, a psychological connection.”

As art historian Betsy Fahlman, a professor of art history at Arizona State University, puts it, “For Critcher, coming West was a transformative experience.” Among her work produced in Taos, Fahlman and others consider Pueblo Family (1928) one of her strongest. At 30 by 30 inches, it’s larger than many of her canvases and reflects the artist’s interest in Modernism. Unlike traditional portraits, the two Pueblo models are painted in profile and rendered almost as secondary figures behind a large pottery jar of flowers. The table under the jar is covered by a woven textile with bold diagonal lines in black and white. Fisher points to hints of inspiration from Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin in the piece, noting that Critcher was clearly keeping up with changes in the art world. Indeed, in 1945 the artist wrote: “The more modern artists have the right of way now, and maybe that is best.”

Taos Grandmother | Oil | 24 x 25 inches | Date Unknown | Collection of the Brinton Museum, Gifted by Mr. Toy D. Savage, Jr.

Another sign of Critcher’s contemporary perspective is visible in Hopi Pottery Maker (1927), which she painted while spending two months on the Hopi reservation. On a shelf behind the pottery maker are painted pots of varying sizes and shapes. Among them are tall, cylindrical pieces characteristic of a style championed by Santa Fe artist Frank Applegate, who encouraged Native artists in the 1920s to create works specifically for the burgeoning tourist market. Waguespack argues that while other painters were looking at Native American subjects through an anthropological lens, Critcher painted the Hopi potter as an “innovative, entrepreneurial woman, not stifled in tradition but engaged in real life.”

Following her summers in the Southwest, Critcher continued to travel and paint, spending time in Mexico, Nova Scotia, New England, and New Orleans. She created still lifes and some landscapes, although portraiture remained her primary focus. One of her most well-known paintings, Indian Mystic, sold a few years ago at Sotheby’s auction in New York for $254,500 — too late to benefit the artist.

Hopi Pottery Maker | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 29 inches | ca. 1927

Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art. Gift of Toy D. and Helen Savage, 1996 (1996.1.1). Photo by Blair Clark

Never married and without children, Critcher outlived her money and spent her later years with a niece in Virginia before dying in a nursing home in 1964 at age 95. Perhaps because she was virtually alone by then, her first name was misspelled as Catherine on her gravestone and never corrected. It’s another of the ways she has yet to receive her just dues, Koenig says, adding, “I’d love to see her receive the respect she deserves, not just as a female artist in the Taos Society, but as an important American artist of the early 20th century.”

No Comments