02 May Collector’s Notebook: A Quest for Understanding

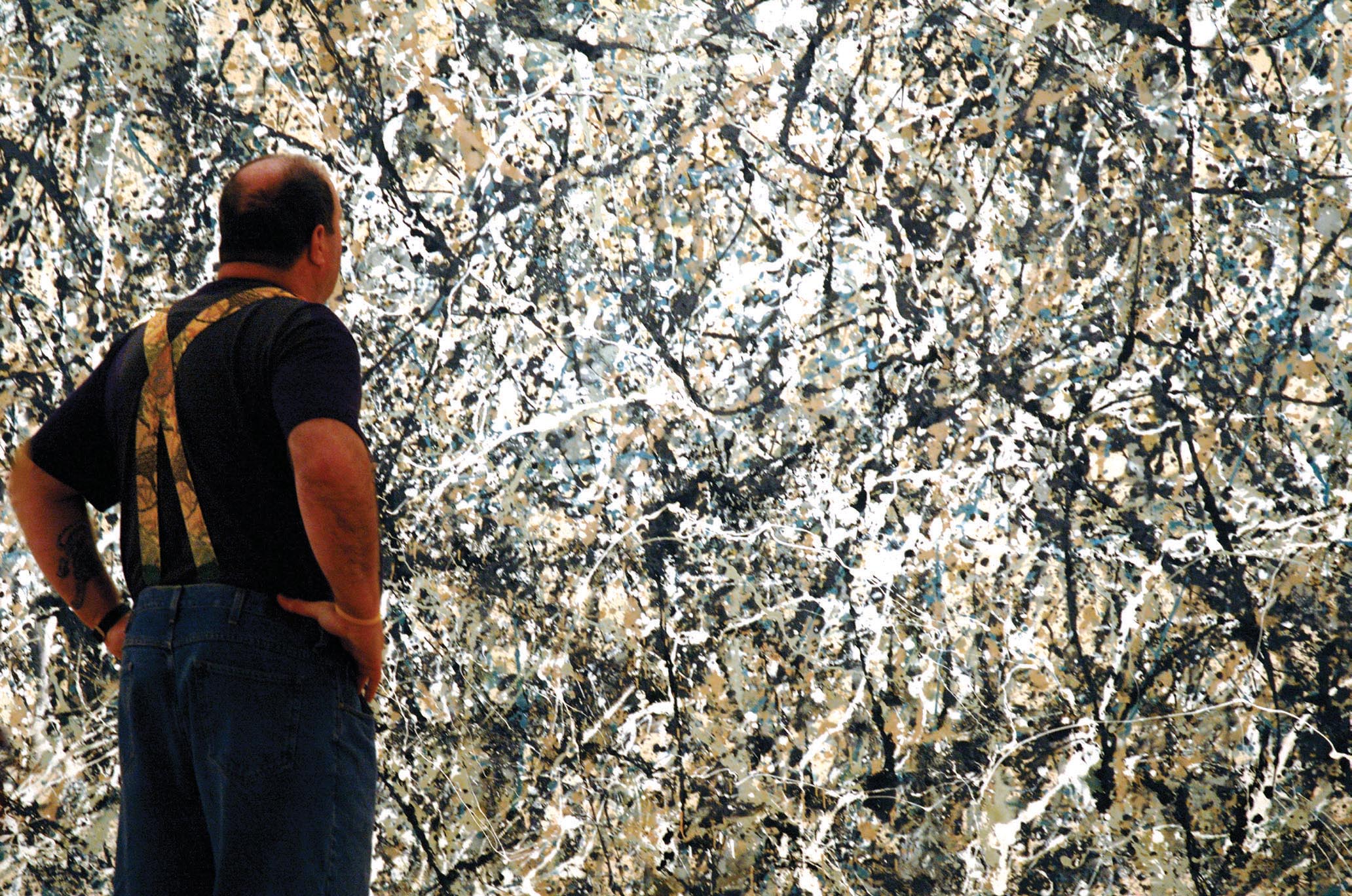

An astute art collector once told me that whenever he’s in Manhattan, he visits the Whitney Museum of American Art to sit on the bench in front of an immense Jackson Pollock drip painting. The collector doesn’t do this because he likes the painting. He visits the Pollock, he says, because he doesn’t like or understand it.

Recently, when I asked if the Pollock painting made sense to him yet, he said he thinks he understands it. Maybe. What did he understand, you wonder? I didn’t ask because it doesn’t matter. I knew he wasn’t searching for proof of the painting’s validity; he had read plenty of critical essays on Pollock’s drip paintings to know why they are considered pivotal works in the American post-war art movement. And he’s astute enough to understand that liking or disliking artwork is a matter of personal taste.

So, why waste time looking at art you don’t like? That question is exactly what this issue’s column addresses.

But first, a disclaimer: We’re not talking about spending time with art that repulses you. We’re talking about the importance of stepping out of your comfort zone and exposing yourself to art you don’t understand. Maybe abstraction, conceptual installation, or performance art bothers you. Whatever it is, just remember that most artists are not willfully trying to upset you; they don’t even know you. So, next time you’re confronted with art that makes you angry enough to want to take a can of spray paint to it, pause and consider the reasons why. If you allow your mind to plumb the depths of your unease, kudos! You are ready to take your understanding of art (and yourself) to the next level.

Step One: Think Like an Artist

Collectors are instinctively curious. They enjoy learning how and why something came into being. They love adding knowledge to their understanding of the world. And sometimes art causes sharp negative reactions. It’s not always logical, but it’s always valid. The feelings art inspires are entirely your own; no one can make you feel anything. Exploring your reaction to art, participating in the experience, is what art is all about.

Many artists habitually check out art that bothers them. While it may sound like an unproductive afternoon spent with stuff that doesn’t support their ideals, artists know something is happening internally when art gets under their skin, and that internal disruption can lead to personal artistic breakthroughs. Artists often say that making art is problem-solving. There are a million decisions that go into every art piece. No matter how realistic a painting might appear, it is still a whole bunch of abstract brushstrokes laid side-by-side, creating familiar patterns in the viewer’s brain that signal recognition. But when those abstract brushstrokes, no matter how they are configured, stir an emotion, the question to ask is, what am I picking up on and why?

Here’s an interesting bit of science: Art may ruffle your feathers for reasons beyond subject matter — or lack thereof. If you’re anything like Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky [1866 – 1944], color may affect you in strange and palpable ways. Kandinsky, a pioneer of abstract painting, had the neurological condition known as synesthesia. For people with synesthesia, the brain reroutes sensory information through other unrelated senses. Within Kandinsky’s brain, music was assigned various colors. The sound of trumpets registered as red, for example, and an old violin was orange. Violet connoted the deep notes of an English horn or a bassoon; light blue appeared with notes from a flute; and dark blue shone from a cello. Kandinsky began his painting career by depicting things more representationally, but as music came to play a bigger role in his painting, these later abstract works, he explained, were painted symphonies.

Knowing what is rumbling around in an artist’s brain, such as Kandinsky’s, adds depth, character, and connection to both the work and the artist. Curiosity — even about works that you initially find uninteresting or upsetting — is the key to unlocking this world.

Step Two: engage Discontent

Yasmina Reza’s play Art centers around a white painting that one of the characters bought for $200,000. Serge, the proud owner, can’t wait to have his two best friends see the painting, but things don’t go as he’d hoped. His one friend, Yvan, is ambivalent and wishy-washy — much like he is in life — and the other, Marc, the engineer, is aghast and feels affronted by his friend’s choice of a totally white canvas. He simply can’t understand why anyone would spend that much money on something that is, in his mind, “shit.”

This painting becomes the fourth character in the play. Its role is to goad the men into confronting deeper issues in their lives and friendships. Because of the painting, each man’s fears and foibles are laid bare. Ultimately, Serge, in utter frustration, hands a felt tip pen to Marc and invites him to draw on the painting if he thinks it’s so awful.

Plenty of subtext here begs the question: How do we deal with people who think differently than we do? Of course, when a friend’s taste in art, books, music, or movies leaves us wondering why someone we thought we knew liked that, we probably won’t kick them out of our lives, but something has been revealed in the friendship. While it’s silly to end a friendship over a painting, we do end friendships over personal opinions all the time. Consider the last time you had a constructive conversation with someone whose view on the environment or politics was the opposite of yours. Be honest. Did you both speak calmly and respectfully and, as a result, grow in your knowledge of an issue and your opinion of one another?

In a recent essay for The New York Times, columnist David Brooks argues that society has become sad, lonely, angry, and mean “in part because so many people have not been taught or don’t bother practicing to enter sympathetically into the minds of their fellow human beings.” He suggests that the decline in people attending museums, galleries, classical music concerts, opera, and ballet may contribute to this downfall. Art, he insists, provides access to other people’s worlds, which is how we learn empathy. Without art appreciation, we struggle to get along.

Step Three: Expand Your Mind

Today, we love the Impressionists. In the late 1800s, however, the term “Impressionism” was coined by critic Louis Leroy to make fun of the 30 painters who had banded together to hold exhibitions because the salons in London and Paris refused their work. This isn’t an anomaly in the art world; it continues to happen today. But it does shine a light on the difficulties artists face when exploring new forms of expression.

For seasoned collectors, the concept of what is good art has most likely changed and evolved, too. You may even have a few pieces of art relegated to back bedrooms or hidden in closets. These things don’t speak to you any longer; you’ve moved on.

Consider for a minute: why? Was it that you’ve seen much more art and have a broader knowledge of how things are made and the level of skill required? Do you have a better understanding of the creativity, artistry, and bravery that went into creating that piece? Are you no longer challenged by those older works?

Perhaps part of your evolution as a collector came with the desire to be an active participant, to feel more engaged with the things surrounding you. Engaging with art may mean it challenges you, but it may also mean it allows you to disengage from work and let your brain live in a different headspace for a while.

Consider this: If art is resonating with you, something is present in your body, mind, and emotional makeup that hears its name being called. That’s what’s happening: The art is calling to you. And sometimes, a work of art is calling and making you uncomfortable because you don’t understand what’s happening. Take a chance if you’re up for it, and approach this work as though you’re on a quest for artistic knowledge. But really, the search results in a deeper understanding of yourself.

Rose Fredrick, a curator, writer, and strategist for artists and nonprofits, shares shares her extensive knowledge about the inner workings of the art market on her blog, The Incurable Optimist, at rosefredrick.com.

No Comments