09 Sep Perspective: Mabel Dodge Luhan [1879–1962]

Mable Dodge Luhan was a woman of contradictions.

She is among the most influential figures in American art, but she was never an artist. She was a towering figure in the cultural world but stood less than five feet tall. She was always inviting people over for dinner, but when they knocked on her door, she often greeted them with a “What are you doing here?” She gave the biggest and most celebrity-filled parties in the history of the American Southwest, yet she often retreated to her bedroom after they started.

Luhan — and her impact on American culture during her more than 40 years in New Mexico — is the subject of a traveling exhibition called Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company: American Moderns and the West. The exhibit opened in May at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, New Mexico; moves to the Albuquerque Museum from October 28 through January 22, 2017; and then travels to the Burchfield Penney Art Center, in Luhan’s birthplace of Buffalo, New York, from March 10 to May 28, 2017. It displays more than 150 works of art and history, from the Western panoramas by the Taos Society of Artists, to Native American and Hispanic works, to the Modernist works considered avant-garde at the time.

How do these disparate elements and artists all fit into the same exhibition? Simple. In one way or another, each illuminated work was influenced by Luhan.

Mabel Ganson Evans Dodge Sterne Luhan — she was married four times — was born in 1879 in Buffalo as the only child of wealthy but troubled parents. As she grew into adulthood, she traveled across the U.S. and Europe, finding comfort in the boundary-pushing thinkers and creators she befriended along the way.

Luhan lived as an expatriate in Florence, Italy, for seven years. From there, she moved back to New York in 1912. She served as honorary vice president of the 1913 Armory Show, the first large exhibition of Modern art in America. She also hosted a famous Wednesday evening “salon,” where progressive journalists, artists, politicians, socialists, communists and writers gathered for intellectual discussions. During her time in New York, she also wrote for Modernist literary and art magazines and the New York Journal.

“But Mabel did not come from a happy family, and she was a restless soul,” says Roberta Meyers, a Taos playwright and actress who stages one-woman shows about Luhan and who knew her while growing up. “And she had been diagnosed as manic-depressive while in New York. She was always searching. And that’s probably why she seemed to go from cause to cause.”

Her searching encompassed not only social causes, but also, apparently, spouses. By the time Gertrude and Leo Stein told her about New Mexico, she was already married to her third one, Maurice Sterne.

She sent Sterne out west to see New Mexico in 1917. A few weeks later, he wrote her from Santa Fe, “Dearest Girl — Do you want an object in life? Save the Indians, their art (and) culture — reveal it to the world!”

When Luhan joined him a year later, she discovered that she preferred Taos to Santa Fe, and the couple moved north. That is where she finally found the one passion on which she could focus for the rest of her life.

Taos struck Luhan like a thunderbolt. The light was different there. The air was different there. The colors were different there. And the place was endowed with a spirituality that deeply touched her.

“My world broke in two right then,” she said, “and I entered into the second half, a new world.”

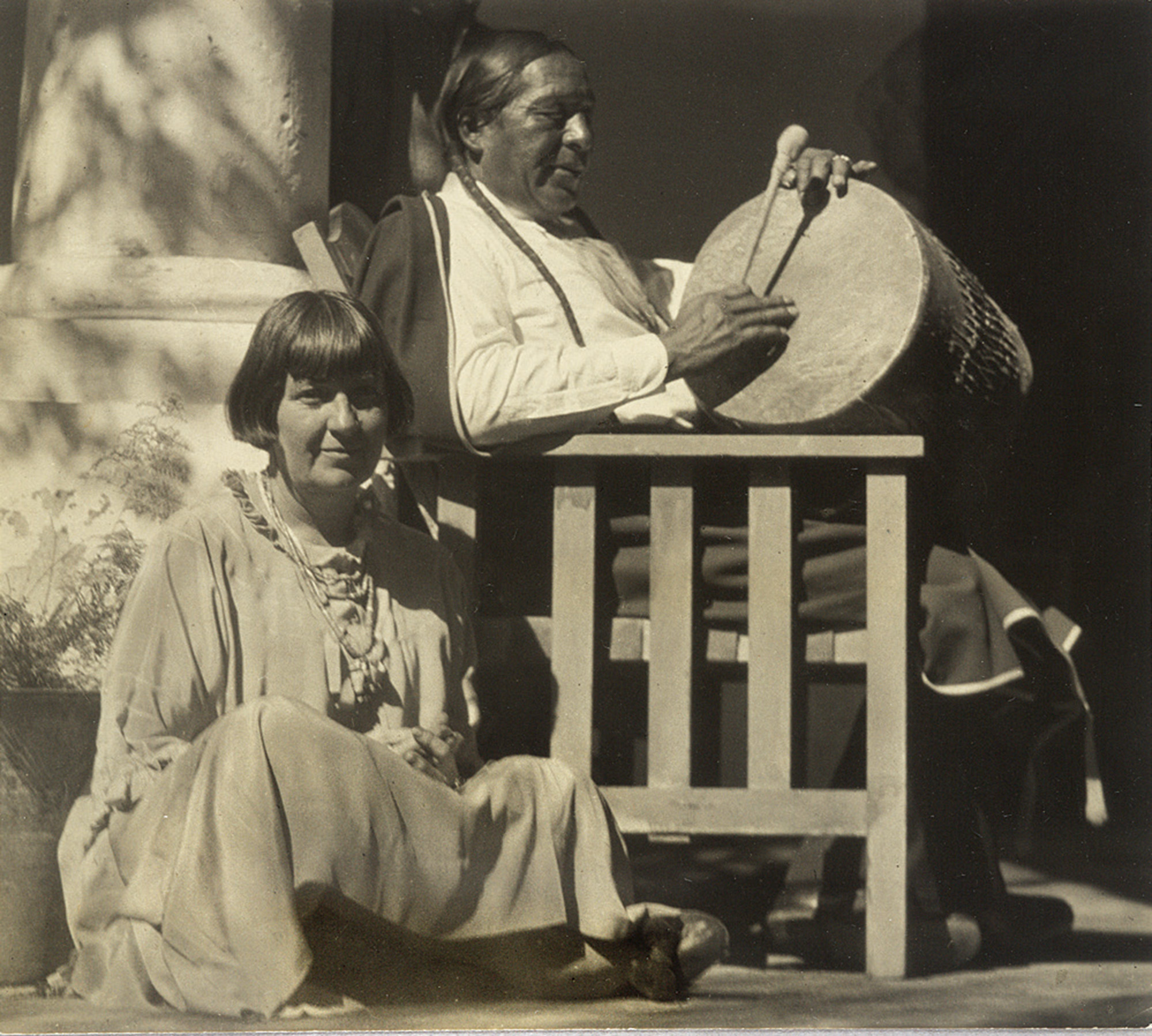

A few weeks after arriving in her new world, she met Antonio Luhan, a Native American from Taos Pueblo. She claimed she had seen him in a dream before they met; and he claimed the same thing.

She divorced Sterne and bought 12 acres of land with Luhan, on which they built a 17-room adobe. In 1923, Tony Luhan became her fourth husband (though he also remained married to a Pueblo woman named Candelaria).

By this time, the Taos Society of Artists had organized and consisted mostly of classic Southwest painters, such as Joseph Henry Sharp [1859–1953]; Ernest Blumenschein [1874–1960]; E. Irving Couse [1866–1936]; Oscar Berninghaus [1874–1952]; and Herbert Dunton [1878–1936].

Despite the vogue status of Taos School paintings and Luhan’s friendships with many of these artists, including Ralph Meyers, she was passionate about Modernism, an artistic movement that could be summarized by poet Ezra Pound’s 1934 admonishment to “Make it new!”

Luhan invited the who’s who of progressive artists to Taos, among them painters Georgia O’Keeffe and Marsden Hartley; photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Ansel Adams; dancer Martha Graham; poet Robinson Jeffers; and writers D.H. Lawrence, Willa Cather, Aldous Huxley and Frank Waters. She hosted many of these luminaries for extended stays at another property she owned, now a celebrated bed and breakfast called Hacienda Del Sol. Today, the establishment’s rooms are filled with books and memorabilia from Luhan’s era.

According to Luellen Hertel, who owns the inn with her husband, Gerd, there’s one famous guest who never left.

“Tony Luhan is still here, according to some of our visitors,” Hertel says. “A number of people have told me they’ve seen him at night — even heard him talking.”

Luhan seemed a person to inspire such tales, and the exhibition celebrating her contributions to creativity is filled not only with stunning art but also the interesting anecdotes behind almost every work.

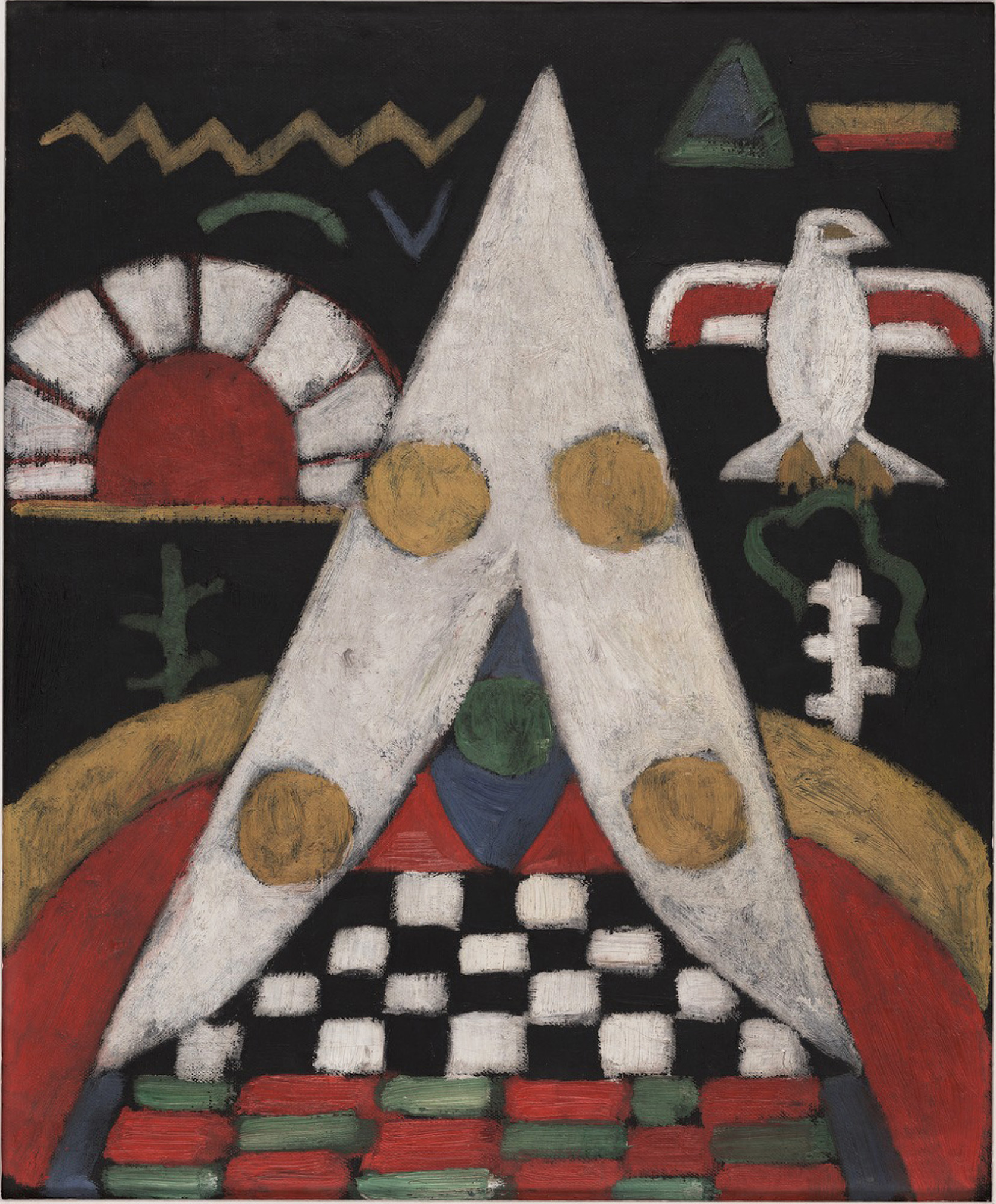

Take, for example, Marsden Hartley’s New Mexico Recollections, No. 12, (1922–1923). Lois Rudnick, co-curator of the exhibition, says this work is one of her favorites because it speaks of the artist’s history. Hartley, one of the first Modernists Luhan brought to Taos, eventually became disillusioned with the area and returned to Europe in the 1920s, she says. But Northern New Mexico lingered in his imagination, and it was in Europe that he created some of his most powerful landscape paintings of New Mexico.

“Mabel was the key figure in shaping a particularly Southwest Modernism, because the Euro-American artists she invited here — whether painters, photographers, choreographers or composers — worked with the cultural ideas and motifs and symbols of Pueblo and Hispano artists. And those Pueblo and Hispano artists were busy creating their own Modernisms in the intercultural exchange that took place, and still takes place, in Taos,” Rudnick says.

The exhibition’s time has come, says Andrew Connors, art curator at the Albuquerque Museum. He believes that Native American and Hispanic artists have always pushed artistic boundaries, but their work hadn’t been recognized as doing so by the Anglo establishment. “For example,” Connors says, “the ancient Chaco Canyon residents were making jewelry with sea shells. And, of course, the nearest sea shells to New Mexico are a thousand miles away. How did they do that? With trade! Modernism is not a newcomer to New Mexico; it’s actually an ancient tradition. Luhan built upon that tradition by bringing a new generation of artists to the region.”

For nearly three decades, Luhan exposed Euro-American artists and writers to New Mexico’s distinctive physical and cultural landscapes and to new aesthetic and social perspectives. Later, she wrote three critically acclaimed books about her years in Taos.

Luhan died in Taos on August 13, 1962. She’s buried in the Kit Carson Cemetery, near the 1,000-year-old Taos Pueblo.

“She left a legacy of Modernism and experimentation,” Connors says. “And she left a legacy, as well, in the artists she brought here who remained here — such as Georgia O’Keeffe — who used the inspiration of the New Mexico landscapes to create a new Modernism. This is a living legacy, because this Modernism is still being explored and created today.”

- “Mabel and Tony Luhan” | Mary Austin Collection | c. 1920s Photo courtesy Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California

- Marsden Hartley, “Rio Grande River,” New Mexico Pastel on Paper | 17.5 x 27.75 inches | 1919 Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Mrs. E. Martin Hennings by exchange

- Dorothy Brett, “Turtle Dance” | Oil on Canvas | 28 x 47 inches | 1947 Millicent Rogers Museum, Taos, New Mexico

- Georgia O’Keeffe, “Grey Cross with Blue” | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 24 inches | 1929 Albuquerque Museum of Art, Albuquerque, New Mexico

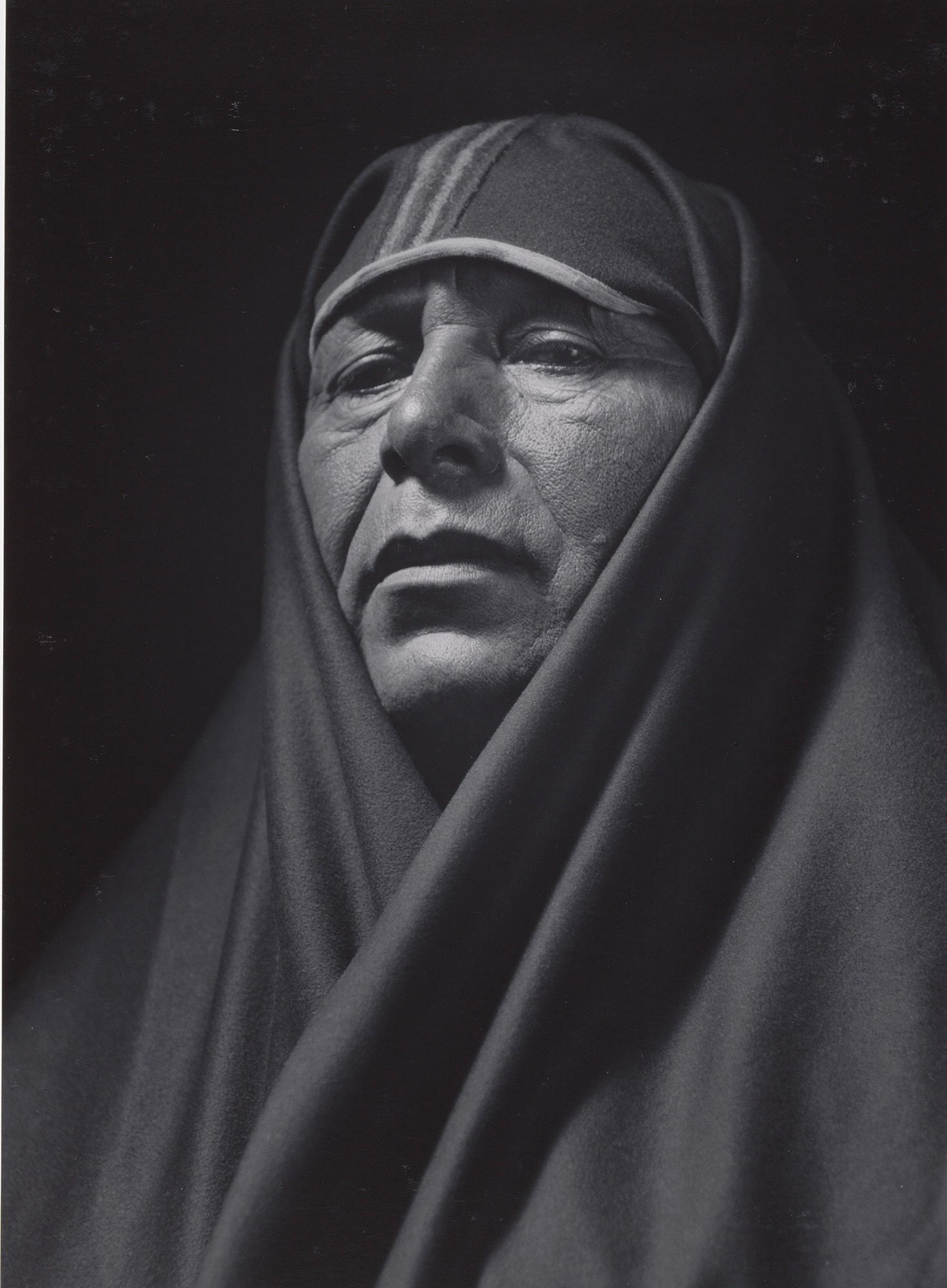

- Ansel Adams, “A Man of Taos, Tony Luhan, Taos Pueblo” | Gelatin Silver Print | 17.3125 x 13 inches | 1930 Collection for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona © 2015 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

- Victor Higgins, “Winter Funeral” | Oil on Canvas | 46 x 60.625 inches | c. 1931 The Harwood Museum of Art of the University of New Mexico Gift of the artist Winter Funeral

- Emil Bisttram, “Taos Indian Woman Plasterer” | Oil on Canvas | 50 x 35 inches | n.d. Collection of Robert and Sherry Parsons Taos, New Mexico

- Marsden Hartley, “An Abstract Arrangement of Indian Symbols” | Oil on Canvas | 20.75 x 17.5 inches | c. 1914–15 Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

No Comments