01 Dec A West to Call His Own

WHEN CONTEMPORARY WESTERN ARTIST DUKE BEARDSLEY was invited to join a bison drive in his native Colorado, he jumped at the opportunity. A skilled horseman who grew up on a cattle ranch, Beardsley assumed bison would behave much like their domestic cousins.

He was wrong.

Wranglers spent much of a morning stalking the bison before abruptly riding in unison to push the herd toward new pastures.

“Two-thirds of the bison ran in the other direction and the other third ran at us,” Beardsley said.

The fifth-generation Coloradan gained insight about a creature that is an enduring emblem of the wild and free American West: Bison don’t obey the rules.

It is fitting that an animal native to a region that values mavericks defies expectations for the sake of some higher goal shaped by ancient instincts. It is a drive that Beardsley is uniquely suited to understand for he is an artist guided by an independent vision that has successfully married the unlikely: traditional Western and Pop art.

Beardsley is among a coterie of contemporary, academically trained artists who are breaking new ground by blending classical images and figures of the West with stylized rendering and color techniques that are decidedly modern.

In his Denver studio, Beardsley is discovering new lands in the footprint of 19th-century forebears who settled the central Rocky Mountains. The 43-year-old artist’s West is mapped by the familiar form of the cowboy but closer inspection reveals that he is an unknown quantity in an uncharted geography that ranges from stark white to saturated red.

“Duke doesn’t paint the Old West; he’s painting the West he sees today,” said Thomas Smith, director of the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum. Two of Beardsley’s paintings hang in the museum’s permanent collection alongside works by contemporary masters including Andy Warhol.

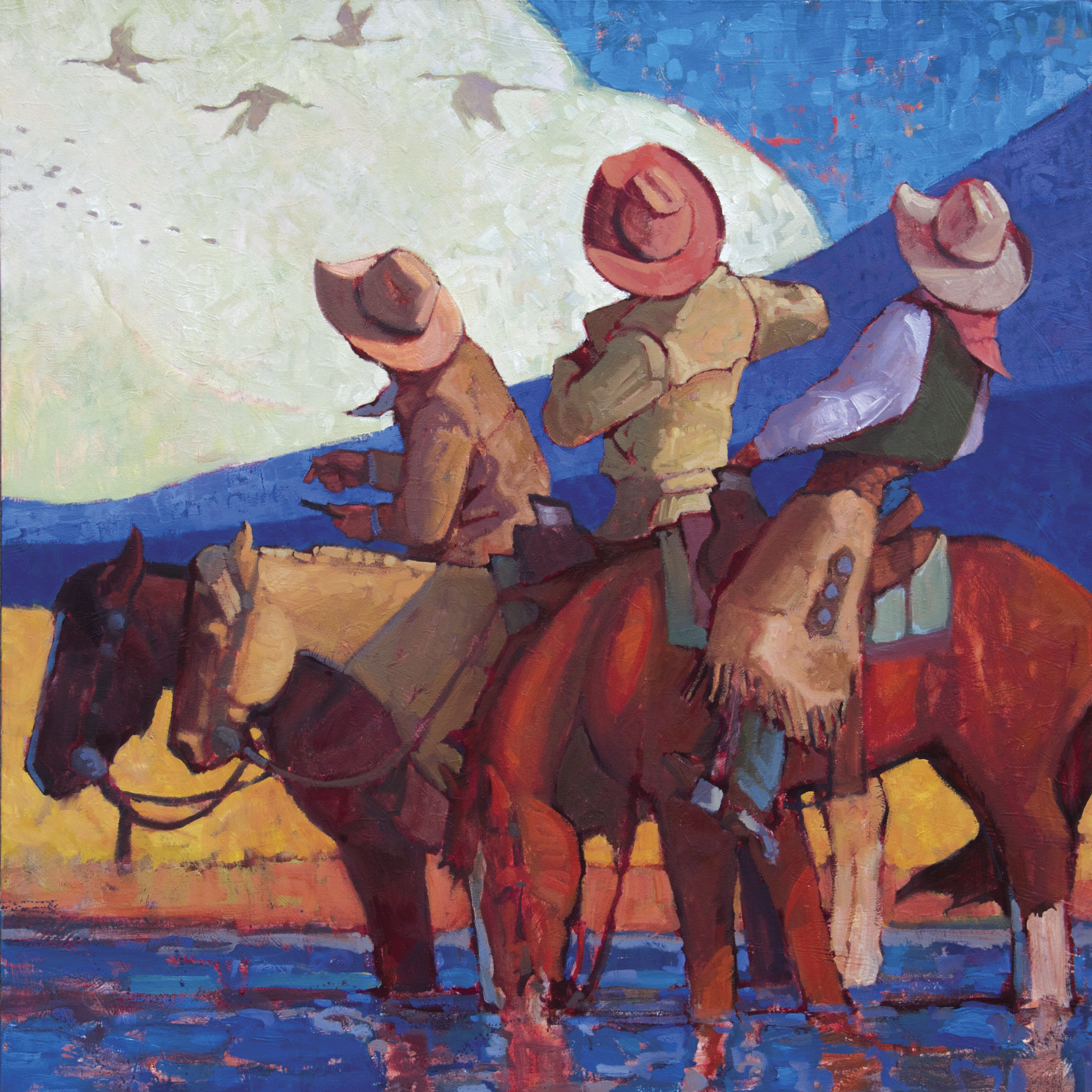

In a region where the intensity of light pushes toward revelation, Beardsley’s cowboys are rugged in form and extroverted in action even as their identity is obscured. A hat angles downward, an arm stretches upward, shadows amass and facial features are subordinated by a limitless landscape that is perceived rather than depicted.

An observer may not notice the expression of the red-toned wrangler stayed for an eternity from throwing a rope in Just a Flick (of the Wrist), but the suspended athleticism of the back-lit figure conveys his mastery of mount and motion.

It is the genius of Beardsley to say so much by painting so little and much is implied where scant brushstrokes are employed.

What emerges from depictions of cowboys riding, cowboys roping, cowboys flanked on horseback by repeating images is a figure as elemental in fact as it is in the nation’s historical and cultural consciousness. There is the cowboy that Frederic Remington and Charles Russell painted but channeled through Andy Warhol.

The subjects of 61 Riders are every cowboy and none of them, simultaneously pointing to principles of individuality and collectivity. Beardsley encountered the technique when he and wife, Tami, traveled in 2007 to China as part of a first-of-its kind contemporary Western art exhibition that included two of his paintings.

The works of Chinese artists using graphic writing elements in multiple images and even across multiple canvases was not lost in translation for Beardsley.

“It speaks to being one in the billions, which is profound,” he said.

The line-ups are a signature style for an artist whose works are featured in such select annual events as the Coors Western Art Exhibit and Sale and The Russell, the sale benefiting the C.M. Russell Museum, and whose paintings are part of premier collections at the Denver Art Museum, Forbes and the Whitney Western Art Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

In Beardsley pieces, the artist is the intercessor. There are no pre-sketches in play, no photographs for reference when he coaxes a canvas into life. Beardsley wrestled with color before he came to the realization that it was not a contest won by strength of will but by cooperation and confidence.

“These paintings are supposed to be directly from me as I have the courage to let them be,” he said. “It took a long time to throw out color the way it needs to be thrown out, to use it instinctively and entirely emotionally.”

Nikki Todd, owner of Visions West Gallery in Denver, said Beardsley began to master a style and speak in a language uniquely his own less than a decade ago.

“There was a big shift where he took that image of the cowboy, plucked it out of context and put it into his color fields,” she said.

The lavender-hued horizon and foreground of many greens in Beardsley’s Caballeros al Anochecer, roughly translated as “twilight riders,” exemplifies what the Denver Art Museum’s Smith describes as the inclination by today’s Western artists to use color as a means of expression.

“The palette for Western artists in the 19th century came from what was visible; it is an idea very much of the 20th and 21st centuries to use colors that have no connection to realism but instead evoke a mood, a feeling about a certain image,” Smith said.

It is in the custom of Western art to take liberties with the genre’s tradition, to refine figures and the environment in a fashion that accords with some truth that strikes the eye of the beholder and is translated through the medium of art.

Laura Fry, Haub curator of Western American Art at the Tacoma Art Museum, said contemporary Western artists are expanding the scope of both subject matter and how it is viewed.

“They are taking those national symbols and working them and reworking them, finding the abstract shapes and adding something new to the conversation,” she said.

Fresh insights on established themes add to the complexity of the region that is the American West, variously robed as a reality or a myth, as a landscape prized for its wildness or as an outpost to be tapped for resources, as a standard for self-reliance and independence or a seat of renegade thought and action.

The Trouble with Chivington, a moody oil by Beardsley anchored by a series of dark, almost flattened, riders on horseback, examines the duality in the form of a single, historical figure, John Chivington. The Union Army hero was first lauded and then vilified for what later was known as the Sand Creek massacre, the unprovoked slaughter in 1864 of Cheyenne and Arapaho by Chivington and a cavalry unit of the Territory of Colorado.

Beardsley is a master of shading and light and that refers to his manipulation of negative space in his paintings as well as his understanding of human nature and the social impulse to raise idols and cast them down.

It is the artist’s prerogative and perhaps his calling to use truth as a form of reinvention, said Meg Daly with Altamira Fine Art, a gallery in Jackson, Wyoming, that represents Beardsley.

“Duke clearly admires and can portray that cowboy life but in a very fresh way. It’s not nostalgic, it’s of the moment,” she said.

It is a moment of lasting impact; one that takes into consideration the debt owed to posterity but is not bound by its dictates, one that acknowledges formal artistic training as a foundation in order to depart from it.

“I used to be consumed with things looking right. Now I want it to feel right,” said Beardsley.

- “Chaparreras” | Oil | 30 x 60 inches | 2009

- “The Trouble With Chivington” | Oil |12 x 36 inches | 2006

- Artist Duke Beardsley

- “Manos y Compas” | Oil | 92 x 60 inches | 2013

- “And I Speak To You Now In The Land’s Voice” | Oil | 62 x 40 inches | 2010

- “Socios” | Oil | 60 x 48 inches | 2010

- “Caballeros al Anochecer” | Oil | 30 x 72 inches | Courtesy of Visions West Galleries

- “Autumn Call” | Oil | 50 x 50 inches | 2012

No Comments