08 Jul The Legacy of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

This January, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith turned 80. As a painter, printmaker, collage and installation artist, curator, lecturer, and political activist, her contributions and critical influence on modern art in America have been astounding. And not because she’s a woman. Or because she’s Native American, of the Salish Kootenai Tribe. Or that, despite facing poverty and discrimination, she came to recognize, at an early age, her calling in the arts. When talking about Smith, it would be a crime to put her in a box and affix a label. No, Smith is one of this country’s most important artists living and working today. Period.

Through art, Smith seeks to communicate the Native American perspective on contemporary life as well as add much-needed context to this country’s historical past. Gorgeous and bold on the surface, Smith’s work is frank and often wry. It has been said that she speaks two languages: that of the Modernist and that of the Native American. As a Modernist, she captivates with color, design, fluidity of mark-making, and concept — the common language of the artist — but it’s her vast knowledge of art history that allows her to use this language as the basis upon which she inscribes her personal history and culture.

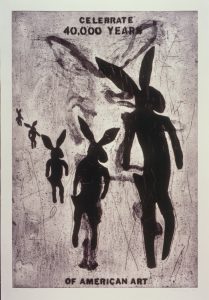

Celebrate 40,000 Years of American Art | Collagraph | 79 x 54 inches | 1995 | Collection of the Whitney Museum, NY

“I always try to walk that line between creating attractive or interesting work, yet with strong social commentary and always with humor — or maybe, the better words would be satire or irony,” Smith says. “Nearly every painting, print, or drawing makes a comment on something, such as war, social justice, the environment, women’s rights, animal rights, racism, Native history. I know that doesn’t sound like funny stuff, but comedians usually deal with these ideas too, so did painters like Bosch. I certainly didn’t invent this way of working — Picasso’s Guernica, Goya’s Los Caprichos, James Ensor’s work, Frida Kahlo, and Louise Bourgeois, plus so many more are role models for me. They demonstrate that, yes, an artist can make an engaging painting that has depth of meaning, but oh, some funny schtick too.”

From the start, Smith has focused on issues endemic to Native people, a message that has been recognized by curators around the world. To date, her work has been collected by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and many others. She has been awarded the Academy of Arts and Letters Purchase Award, the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters Grant, the Women’s Caucus for the Arts Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Living Artist of Distinction Award from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, to name a few recognitions. And she’s earned honorary doctorates from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Massachusetts College of Art, and the University of New Mexico.

The Center of the World | Acrylic, Oil, and Collage on Canvas | 72 x 48 inches | 2005 | Collection of the Artist

Even though she has already accomplished much, Smith is not ready to take it easy; she is, as ever, concerned with issues facing indigenous people and knows there is work yet to be done. Part of her concern is to bring indigenous artists’ work to the forefront, a task that has necessitated Smith to push back against the establishment. “In her 40-year career as an artist, political activist, and curator, Smith champions her Native American colleagues,” says Mindy Beesaw, curator of american art at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. “Smith addresses the white, masculine mainstream with such wit and humor that they often don’t know what happened.”

In her tireless effort to take on the perpetuated Anglicized mythology of the West, Smith has shed light on its gaping flaws, not through a pedantic lens but in the way of the trickster: with levity. While many artists appropriate Native American imagery in their work, Smith turns the tables by appropriating Pop Art symbolic of mainstream American culture as her way of establishing a starting point for the conversation she wants to have.

Herding | Oil on Canvas | 66 x 84 inches | 1985 | Collection of the Albuquerque Museum

“Tricksterism,” she explained, “can be part of making art, writing, or doing theater. The creator, inventor, satirist must show the flip side of things. They turn things upside down in order to lampoon the immorality or insincerity of politicians, priests, or heads of governments, or show the human condition. Shakespeare, Krazy Kat, the Muppets, Stephen Colbert, Wile E. Coyote, Will Rogers, Bugs Bunny all show us human beings at their worst and maybe their best too. Wile E. Coyote and Bugs Bunny are surely taken from our traditional Native American creation and teaching stories. They mock greediness, failures, shortcomings, and narcissism — the foibles of human life. They hold up a mirror for we humans to see ourselves, in the flesh, warts and all.”

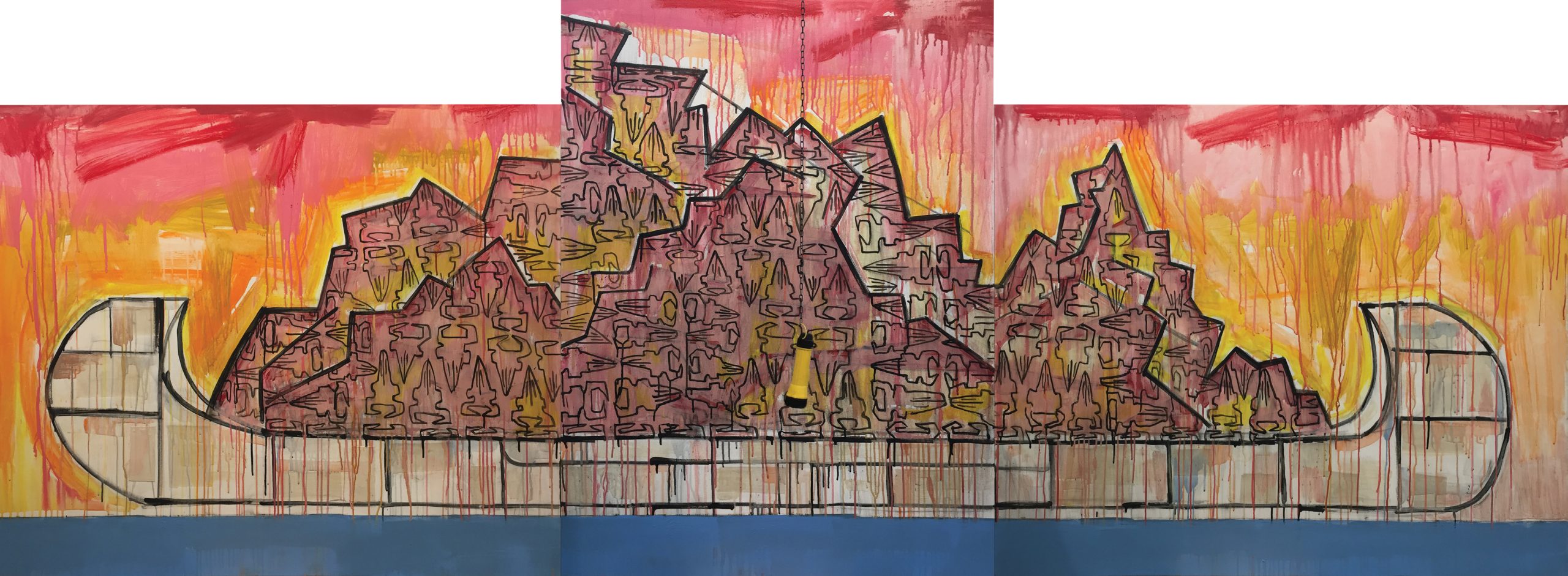

Trade Canoe: The Dark Side | Acrylic, Collage, and Charcoal | 160 x 40 | 2018 | Collection of the Artist

But, after a cursory scan of museum collections, one must ask: is anyone listening? “Oh yes,” she says, “there are definitely new rules; museums are actually seeking Native artists and especially the young ones, beautiful, brainy, articulate, well-educated, well-traveled. It’s a new era. Partly, social media should receive credit. Partly, it’s because these young talented artists — including my son Neal Ambrose-Smith, who is chair of the art department at the Institute of American Indian Art, our prestigious Indian college in Santa Fe — these artists are easier to find due to their websites. They are savvier than my generation, and their work is more sophisticated when they arrive on the art scene.”

Where Native artists have not made strides, however, is in the private market. Smith sees this as an economic issue. “We don’t yet have Native CEOs in the corporate world, although our CEOs might be tribal chairmen or arena directors of a powwow, but those jobs don’t pay that well,” she says. “We also don’t have Indian peoples on the boards of museums which could help direct the museum collections with more Native inclusivity. Our tribal peoples serve on boards at our Tribal Colleges, which have no contact with the museum world.

Skypeople | Lithograph | 36 x 22 inches | 2011 | Collection of the University of New Mexico Museum of Art

“It’s a fact of life that we live in two different worlds with differing agendas; ours is about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and we stand at a survival level, there’s no room in that budget for purchasing art,” Smith adds. “We use our art for trade goods and trade with each other. We also give it away to fundraisers for scholarships, for food pantries, and to raise money amongst ourselves for helping a tribal member whose house may have burned down because, of course, few have any insurance. That’s a luxury for white people. Americans don’t know much about subsistence living, except those of us who’ve lived in that world. When I see homeless people, I cross myself and say: There but for the grace of the Creator go I.”

Trade Canoe: For the North Pole | Acrylic on Canvas | 60 x 160 inches | 2017 | Collection of Crystal Bridges Museum

When asked about the specific challenges for women, Smith says she hopes to call attention to violence and under-representation. “As Native women, our situation is somewhat the same as the #MeToo movement but also somewhat different in that #MeToo is not about missing and murdered women,” she says. “We, in the Native community, have a real genocide going on, especially on our northern border as well as our southern border and across the country on our reservations and in our Indian towns. Indian women go missing from parking lots at grocery stores, gas stations, or walking to and from work. Up until now, police departments have ignored the pleas of the Native communities. We’ve been doing art shows, news interviews, and public shout-outs to garner attention for this horrific situation in our communities. So again, we fall off the charts when it comes to anything like being featured in magazines, museums, or galleries; Native women are still not recognized in these arenas.”

Of the artwork Smith has created thus far, it just might be the pieces she’s held onto that offer the most intimate look at her life. “Often, you’ll see in an artist’s personal collection some work that is quite different from the work in public collections. It might seem unfinished or scruffy — and we ask, ‘Why would they hang on to that thing?’ Well, they feed off it; it speaks to them, is a muse for them. I’m talking about yours truly here. So yeah, I have a painting that is littered with divots of collage, some bread wrappers and wallpaper and signage that tells us to learn Spanish and ‘Get Ready, Get Set, Grow’ — oh yeah, that is a turn-on for me. I have lots of paintings that I like, not because I think they have great beauty or composition, but no, I like them because I have some small secret message or image that only the very discerning will ever notice, and it’s my way of leaving a message for when we’re all floating in the solar system and my painting is headed to Mars to give a message to some space personage out there because Earthlings didn’t take notice and trashed the place, making it unlivable.”

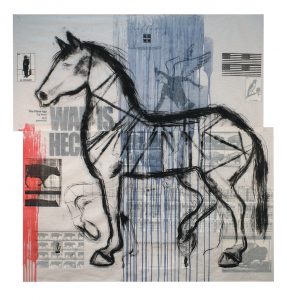

War is Heck | Lithograph with Chine Collé | 58 x 56 inches | 2002 | Collection of the Whitney Museum, NY

After 80 years, thankfully it doesn’t sound like Smith is close to retiring. When asked what she hopes her legacy would be, she says simply, “That I led a purposeful life and moved the needle of Native recognition in the arts, maybe a skosh.”

How true the words of Smith’s long-time friend, Dorothee Peiper, who says, “Native American art has so much to teach the world.” Perhaps we’ll start listening before it’s too late.

No Comments