30 Dec The Story of a Storyteller in Clay

Celebrated Native American potter Diego Romero wants to set things straight, for the sake of historical and popular records. Asked to provide reasons the multitalented artist chose clay, Romero said it was the other way around.

“Clay chose me,” said Romero, whose ceramics have been accorded some of the highest honors in the land and overseas. Interestingly, one of his pots is in the collection of the British Museum, arguably best known for holding the Rosetta Stone.

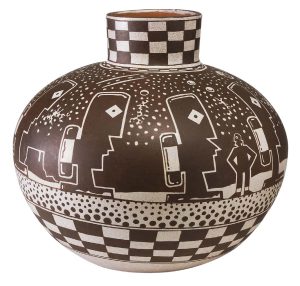

Olmecs | Ceramic | 9.5 x 9.5 inches

Romero is a mix of contrasts. He is half Native American, half Caucasian American. He is an artist capable of replicating the traditional forms and designs of his Pueblo ancestors in clay, in an area now known as the U.S. Southwest. He is a clay whisperer who has pushed the medium to its maximum limit. He is a man of easy humor, and he is a man of plaintive sorrow.

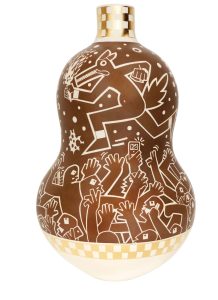

Coyote Stealing Fire | Ceramic | 6.5 x 13 x 13 inches

Curiously, the past, present, and future, as well as many of the facets of Romero’s personality and talent, find their natural expression in his pots, which emerge from a method of coiling and heavy manual labor, including burnishing with stone and by hand. Geometric patterns give way to centerpieces that are strangely and magnificently peopled by comics-style characters, the central one of which is Romero’s alter ego, Chongo, so named after a tribal hairstyle.

The Thinker | Ceramic | 7.5 x 15.5 x 15.5 inches

It nears an offense against art to call Romero’s works “pots.” But they are earthy and exude his down-to-earth approach to all facets of his life from art to parenting his five children.

Romero’s Odyssey, which ultimately led his pottery to be celebrated in renowned institutions such as the Renwick Gallery, an arm of the Smithsonian American Art Museum also known as the “American Louvre,” and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, did not involve mythic creatures like sirens, Cyclops, or the spellbinding enchantress Circe. Yet his beginnings in Berkeley, California, and journey to the halcyon halls of major museums, were informed by challenge, adventure, soaring defeats, and plunging triumphs — much like the protagonist in Homer’s epic.

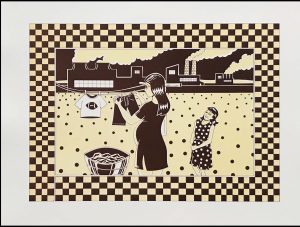

Pueb Fiction | Print | 19.5 x 16.5 inches

Like his father before him, Romero is a member of the Cochiti Pueblo tribe and today infuses his visual arts with truth, beauty, and goodness. From his Santa Fe, New Mexico studio, he creates work that provides cultural, political, social, and historical commentary that tends to wake sleepwalkers, make waves in still waters, and animate observers. No one examining a Romero piece leaves the same way they came in. His vessels possess the power to revive wonder and foment ideas; they are a catalyst for new angles of view.

Girl in the Anthropocene | Print | 14.875 x 21 inches

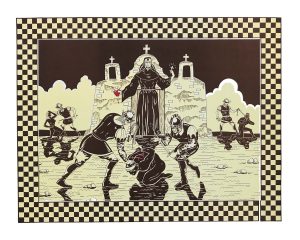

Romero easily mixes myth with figures in a manner associated with the Mimbres, a centuries-old and ostensibly vanished people and culture tied to what is today a region of New Mexico. Yet Greek artisans of antiquity — those fashioners of amphorae and other objects over the ages that saw black figures on red vessels and red figures on black ones — are no longer alone in bringing to life the heroes of the Ionian poet Homer. Odyssey, commissioned by enthusiasts of Romero’s mythic depictions, chronicles in clay all that is at play between Odysseus and Circe, detailing how she bewitches him and further delays his return to his wife, son, and kingdom after the Greeks’ atrocious victory in the Trojan War.

Theater of War | Ceramic | 5.5 x 14.5 inches

Romero is bold; he has no fear of lifting from ancient mythology a contemporary image of a protagonist succumbing to the allure of delusion in the face of truth. From his earliest recollections, Romero was drawing. His youthful passion for comics led him to illustrations, and his fascination with those images sparked a strong desire to decipher the words that told the rest of the story. “Comics were the reason I wanted to learn to read,” he said.

Saints and Sinners | Print | 20.06 x 26.44 inches

Romero, like the central figure in a multi-layered drama, is on the path, it seems, that was laid out for him long before he took his first step. Timing is certainly an element, but as with all epic tales, there is more, to paraphrase The Bard, in heaven and earth than philosophies dreamt of.

It is arguably a truism for certain artists that their hearts and hands cannot rest until what exists in their mind’s eye is brought forth as material objects in such media as paint, clay, or bronze.

Knot Bearers | Ceramic

His mother, a Berkeley intellectual, and his father, a Korean War veteran who lost a hand in the conflict, seeded in their children a love of ideals, stories, and art. Mateo Romero, an award-winning native painter and sibling of the ceramicist, underscored his brother’s artistic acuity. “His drawing ability has always been superb, even as a little kid,” he says. “And he has a great sense of hard-edged line, positive and negative space, and composition.”

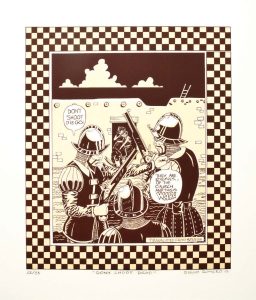

Don’t Shoot Diego | Print | 19 x 16.375 inches

Romero is heavy in academic training, including a Bachelor of Fine Art from Otis College of Art and Design and Masters of Fine Art from University of California, Los Angeles, all of which has fostered that mysterious je ne sais quoi quality of his oeuvre. At every crossroads, Romero has encountered a figure of encouragement. Some teachers nurtured him, others challenged him. The result? Diego Romero. And Chongo.

Romero initially resisted attempts to bring a contemporary edge to traditional style work. Yet once he moved toward that synthesis, the proverbial oyster opened. Contrary to the adage, timing is not everything. Talent is so much more. Yet timing did play an important role in bringing Romero’s vessels to critical and popular acclaim. He exhibited his bowls at the storied Santa Fe Indian Market at a time when Native pottery had gained prestige in august art circles, including those led by international ceramic art critic and author Garth Clark. Commercial success followed.

The Renwick asked Romero to create a pot that would provide commentary on certain political realities. While the artist is willing to leap wholeheartedly into issues of heated debate, he is just as devoted to respecting the vision of a given patron. In this manner, together, he says, ideas become one reality. The work that landed at the Renwick Museum is titled New Genesis. The scene depicts a climate-changed world in which the monuments of humans are swept aside, and the life of the sea washes into symbolic and physical view through the form of marvelous marine creatures.

Cara | Lithograph | 24 x 24 inches

There is no real ending to Romero’s story because, like the artist, animation keeps overtaking what is static. And that phenomenon describes his pots. Romero once asked his mother, a blond with blue eyes, why she sought out and and married his father, a dark-eyed, serious-souled man. Her answer was as simple as it was profound: “We were making the world a better place.”

The same impetus drives Romero, his famed artist wife, Cara, and his painter brother. “My mother and the Berkeley of the 1960s are long gone,” he says. “But the ripples are still going out.”

No Comments