04 Aug Perspective: Ahead of their time

In 1905, the National Arts Club in New York City hosted a prophetic exhibition about the changing fate of American Indians. The exhibition showcased Native Americans in sculpted, painted and photographic art in an attempt to capture the incredible variety of the cultures while it was still possible. Among the exhibitors were two prominent artists united with a common purpose.

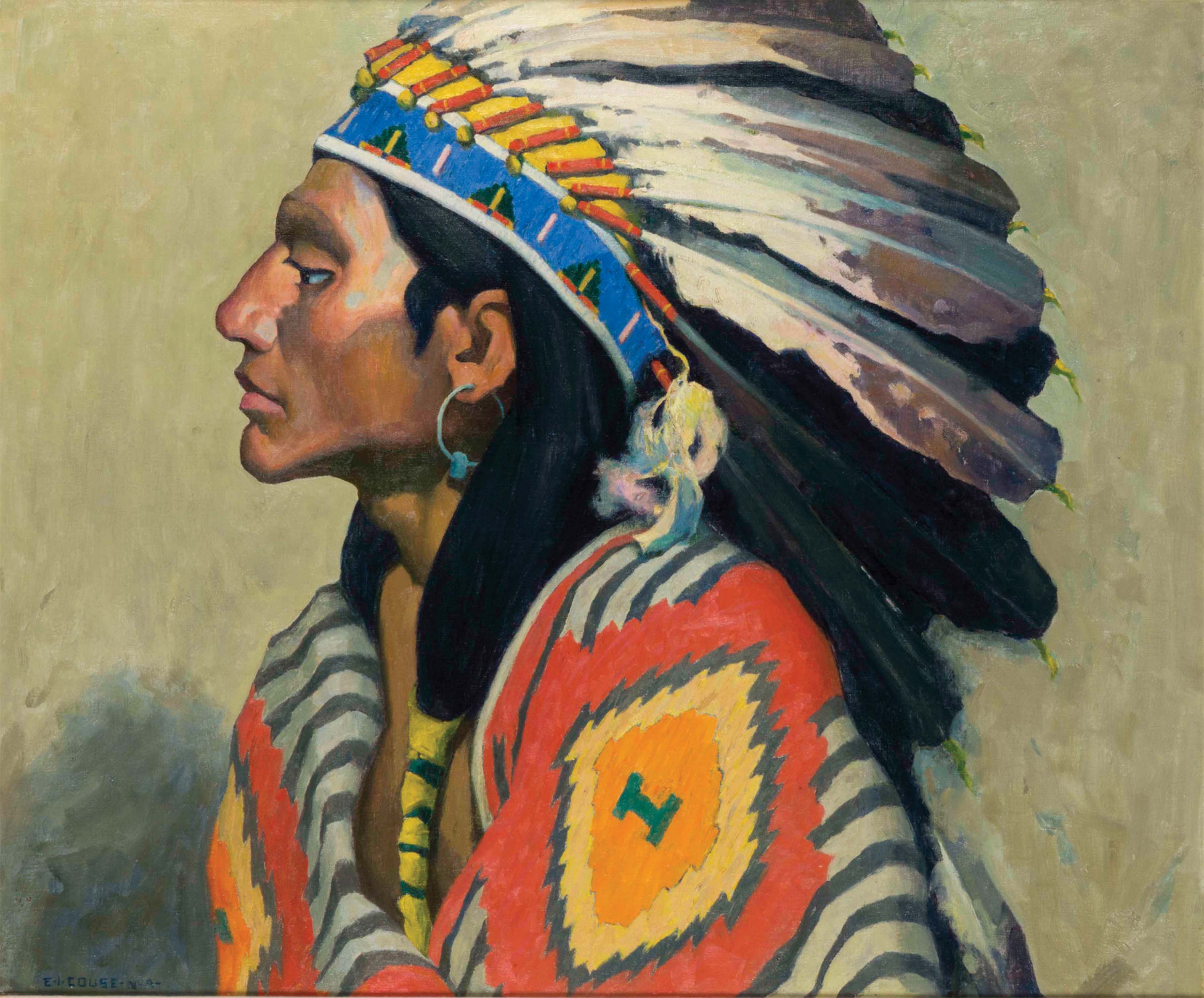

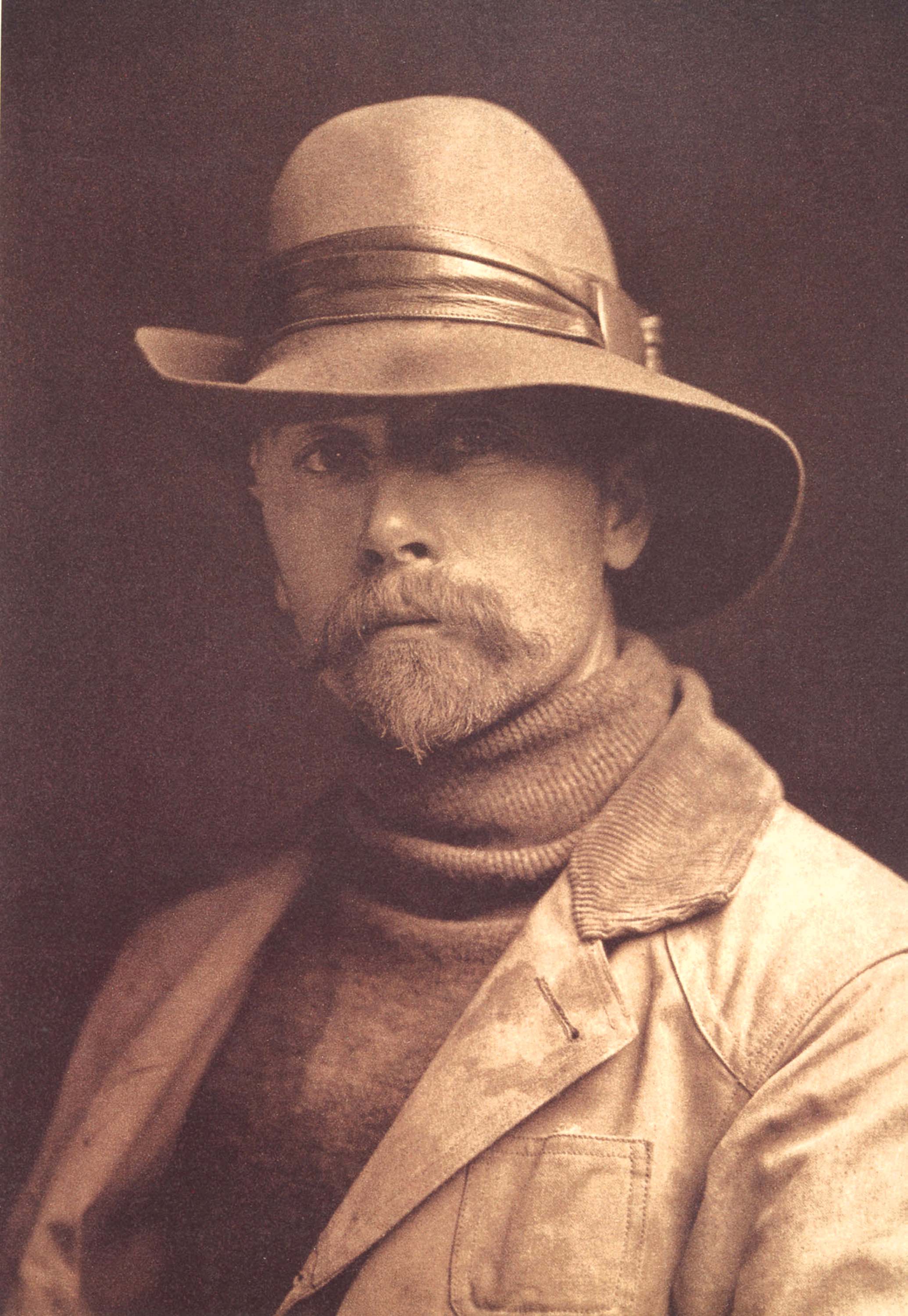

Eanger Irving Couse [1866–1936] was already recognized as a highly skilled oil painter specializing in American Indian subjects. Edward Sherriff Curtis [1868–1952] had come to prominence as a photographer of the same subject matter.

The National Arts Club was founded in 1898 to promote America’s knowledge of art. By then, America — which had always looked to Europe for inspiration in paintings — had begun to look inward for inspiration, and these two American artists had already recognized that Native Americans were a uniquely American subject. Both men empathized with the plight of Native Americans who were popularly, but wrongly, portrayed by the artistic community and media of that era as bloodthirsty savages who needed to be anglicized, placed in government schools and moved to reservation land.

In 1906, the year following the exhibition, an article in the New York Herald described Couse’s interpretation of Indian subjects as unequaled among painters, being “a delicate balance between poetry and realism … depicting the home life and legends of the North American Indian.” That same year Curtis would receive the initial financial backing of J.P. Morgan to finance his great opus, the 20-volume The North American Indian, which contained a foreword by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Midwesterners by birth (Curtis was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin; Couse in Saginaw, Michigan) both men in their youth would encounter Native Americans and eventually make their way to the American West. When the Curtis family moved to the Seattle area, the young photographer was fascinated by the last of the Seattle chief’s daughters, Princess Angeline. His photographs of the elderly Salish Indian became a turning point in his photographic career.

Couse’s childhood included a familiarity and sketching opportunities with the local Chippewa tribe in the Saginaw area. After completing five years of classical training at the Academie Julian in Paris, Couse lived for a brief period on a ranch his wife’s parents owned in Klickitat County, Washington, where he began painting and photographing his first Indian subjects.

Curtis’ path to prominence was a fascinating one. By age 20, he had become the family’s breadwinner on the outskirts of Seattle. It was subsistence living. Six years later, he borrowed money against the family homestead for a move into the city and began work as a Seattle portrait photographer. Though he found success almost immediately, his career took a turn in 1898 when a chance meeting on Mt. Rainier with a lost climbing party turned out to be fortuitous. The party Curtis rescued included George Bird Grinnell, founder of the Audubon Society, and Clint Merriam, co-founder of the National Geographic Society.

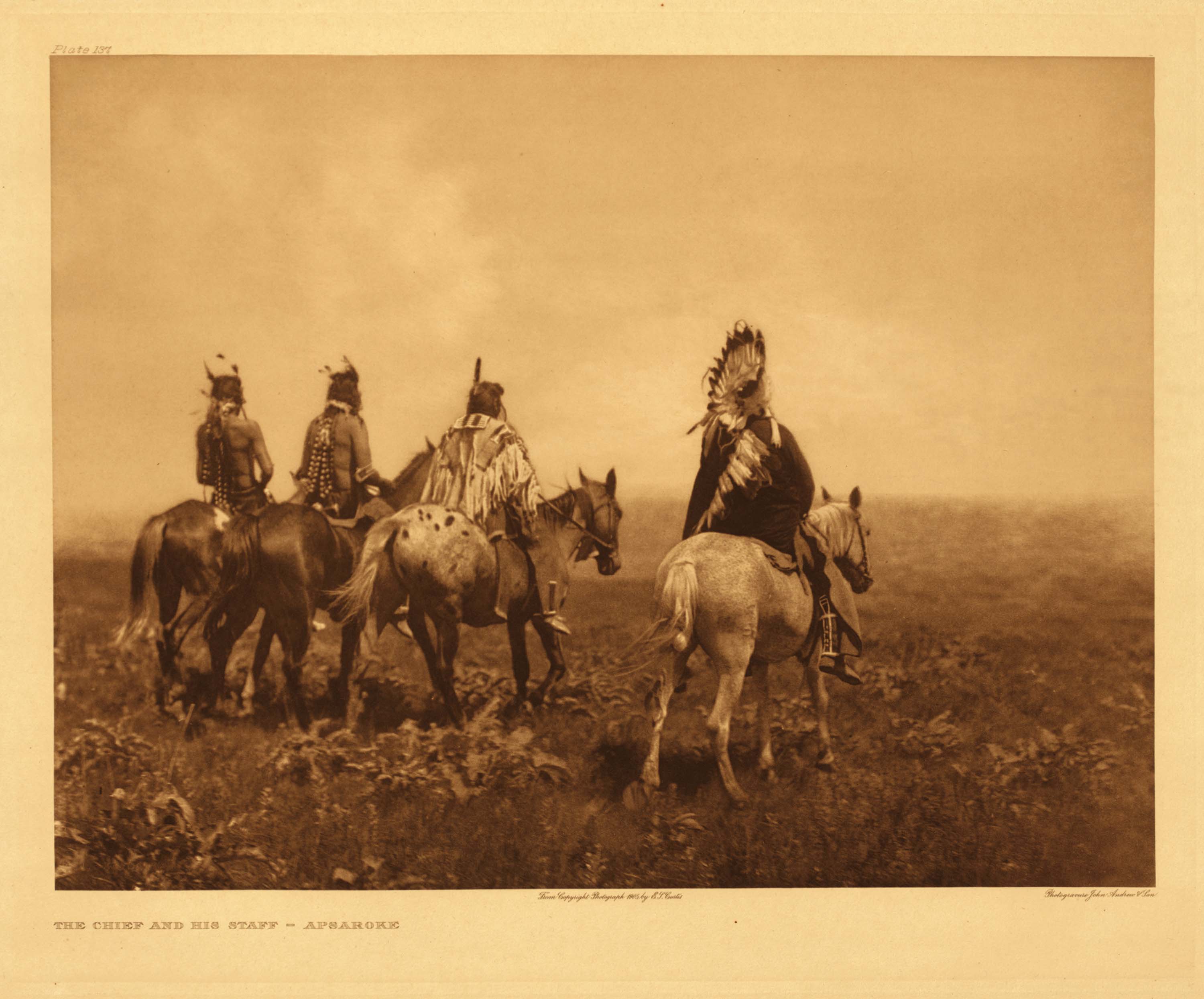

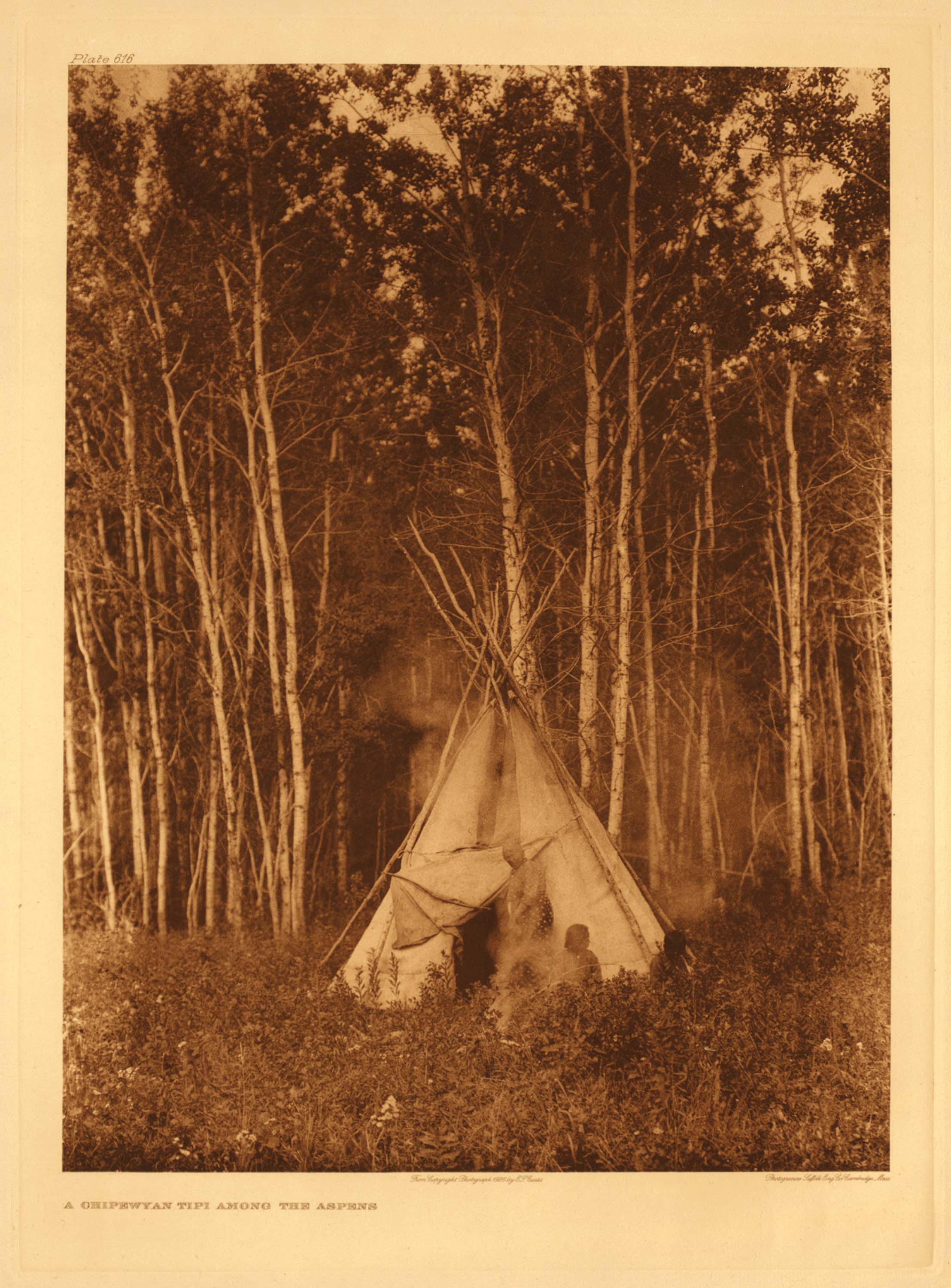

They invited the photographer to explore Alaska with them the very next year and to travel to Montana the following year to photograph the ceremonies of the Blackfeet Nation. Curtis absorbed much of his knowledge of ethnology from these two experiences. From then on, he organized his own Native American photographic explorations, which lasted for three decades and resulted in the publication of The North American Indian.

Couse’s path was more traditional, though guided by a widely appreciated talent. From an early age he showed interest in sketching, but unlike self-taught Curtis, Couse sought academic training. He dropped out of high school to study art, first at the Chicago Art Institute, then at the National Academy of Design in New York and finally at the Academie Julian in Paris in 1886, where he promptly took top academic honors in three separate years. His first solo show of Native

American paintings was staged in 1891 by the Portland Art Association in Oregon. In 1896, he opened his first studio in New York City and maintained studios there until 1928. But as early as 1902, Couse discovered Taos, New Mexico, where he spent summers studying and painting the Indians of the Taos Pueblo. In 1915, Couse was among the six founding members of the Taos Society of Artists and was elected its first president.

As with Curtis’ photographs, Couse’s oil paintings remain widely collected to this day. A major collection is held by the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway, whose forerunner assembled the first corporate art collection in America, and was an enormous patron of Couse. Other paintings are held by dozens of museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, and the Gilcrease, Eiteljorg and Stark museums. A fine collection of 47 of his oil paintings is held by The Couse Foundation, a Taos, New Mexico, nonprofit corporation.

More than 100 years after the mile-stone exhibition at the National Arts Club, the reputation and fame of these two artists continue to grow. Last year saw the release of Timothy Egan’s gripping biography of Edward Curtis, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, and sale prices of beautifully rendered Curtis photogravures have skyrocketed. In May 2012, a 20-volume intact set of The North American Indian sold for $2,882,000 at Christie’s.

Couse’s legacy also has blossomed. In the summer of 2012, The Couse Foundation purchased Couse’s historic home and studio in Taos, New Mexico, along with two studios of his colleague and fellow painter of Taos Indians, Joseph Henry Sharp. The 2-acre historic site contains all its original furnishings and Couse’s collection of artifacts used in his Indian paintings. Tours are available by appointment, often by Virginia Couse Leavitt, granddaughter of Couse, and her husband, Ernest Leavitt. One is immediately transported to the time period of the Taos Society of Artists.

Additionally, the Maryhill Museum of Goldendale, Washington, opened an exhibition in June titled Eanger Irving Couse on the Columbia River, which showcases original Couse paintings of Northwest Indian tribes as well as artifacts he collected for purposes of those paintings. The show will remain on view through September 15.

Both Curtis, with his unique rapport with a myriad of tribes, and Couse, with his beloved Pueblo models, produced bodies of Indian artwork of staggering beauty. In so doing, Couse with his paintbrush and Curtis with his camera were instrumental in pioneering a new, more sympathetic attitude toward Native Americans. The legacy and lifelong commitments of these two contemporaries lives on.

- Edward S. Curtis, “The Chief and His Staff” — Apsaroke

- E. Irving Couse | “Turquoise Bead Maker” Oil on Canvas | 24 x 29 inches | 1925

- Edward S. Curtis, “Princess Angeline”

- Edward S. Curtis, Painted Tipi — “Assiniboin”

- Eanger Irving Couse

- E. Irving Couse | “Grinding Corn” Oil on Canvas | 24 x 29 inches | acquired 1926

No Comments