29 Oct Perspective: Susie Barstow [1836-1923]

“I will overcome every barrier to success,” Susie Barstow wrote in her journal in 1856, “and soon, with the sun rising above every Earthly conflict, make myself a name and position that will influence the whole world.” An aspiring artist, Barstow was 20 years old at the time, and the grandiose scale of her dreams might be attributable to youthfulness. But her self-confidence and determination were solid and remained with her for a lifetime. These qualities, along with extraordinary artistic talent and a strong spirit of adventure, did indeed allow her to overcome barriers and make a name for herself — one that was forgotten by art historians for many years but is now being revived.

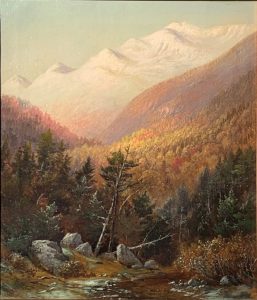

Fall, White Mountains | Oil on Canvas | 13.25 x 11.25 inches | c. 1870s | Albany Institute of History & Art

A painter in the Hudson River School style, whose second wave of popularity was peaking after the Civil War, Barstow was fully aligned with the movement’s aim of sharing a powerful sense of awe inspired by nature’s pristine beauty. And, like her artistic peers — among them Frederic Church and Albert Bierstadt — she was committed to direct experience as the foundation for her art. For Barstow, this meant hiking and climbing as much as 25 miles at a time, in all seasons, in mountains from New England to Yosemite to the European Alps, and sketching and painting what she saw.

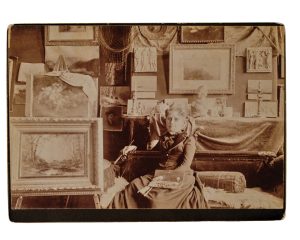

Photograph of Susie M. Barstow in her Brooklyn Studio | 5 x 7 inches | 1891 | Private Collection. Image courtesy of Dennis DeHart

“She really was just dazzled by everything she saw in nature,” says Nancy Siegel, Professor of Art History at Towson University and a scholar and curator with a focus on the Hudson River School. Siegel co-curated two major exhibitions featuring Barstow and other female Hudson River School painters and is the author of the first biography on Barstow, published in 2023 on the 100th anniversary of the artist’s death.

Susanna (Susie) Moore Barstow was fortunate to be born into an upper-middle-class Brooklyn, New York, family that supported her artistic leanings and sense of independence. Her father, a tea merchant, encouraged his daughter’s education and became the first known collector of her art. Barstow attended Rutgers Female Institute and the Cooper Union in New York and joined prominent art organizations, including the Cosmopolitan Art Association. In her early 20s, she began exhibiting her paintings alongside male artists, earning prices comparable to theirs.

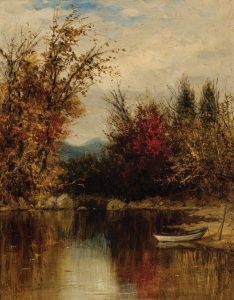

Barstow’s youth coincided with a time when urban Americans were enjoying excursions into nature, appreciating its serenity in a quickly changing world. Tourist hotels and an expanding railroad system made this easier, and in a journal entry in early fall 1856, Barstow described a morning on one such outing: “In the deep valley below me is a clear rippling stream which, widening as it advances, soon opens upon a glassy pond. In the distance, a narrow river winds through the meadow forming by its fortuitous course, numerous little islands — and still beyond is the great, the boundless ocean … Ocean, river, and pond are one vast sheet of silver.” She could have been describing one of her own paintings. “She’s very poetic in the way she writes about nature, and it translates on the canvas for her,” Siegel says.

But Barstow did much more than admire the landscape as an urban tourist. She joined the Appalachian Mountain Club, founded in 1876, and helped blaze and maintain trails and build semi-permanent huts and shelters in the White Mountains and other Northeastern ranges. At a time when women’s long, heavy skirts and narrow-heeled shoes made hiking cumbersome, she and many other women shortened their hiking skirts, wore bloomers underneath, and strode for miles in sturdy boots. Hiking with friends and sometimes female painting students, Barstow carried a satchel filled with sketchbooks, pencils, and watercolors. Nor was she afraid to hike alone. In interviews for local newspapers at the time, she recounted being in the forest by herself when a bear approached. Unfazed, she quietly waited, and the bear wandered off. “When she was by herself in nature, I think she was at her happiest,” Siegel says.

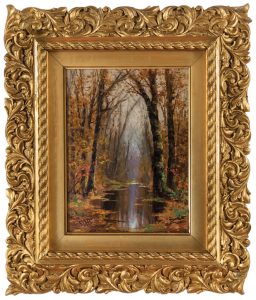

Pool in the Woods | Oil on Panel | 9.5 x 7 inches | 1885 | Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, CT

Barstow’s adventures also took her across the United States and beyond. She hiked and sketched in Yosemite and exhibited her art at the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, among other places. She sojourned multiple times in Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, studying art and climbing mountains. “She never married or had children, so she had the opportunity to live a very independent life,” Siegel says.

Back in her home and studio in Brooklyn, Barstow used sketches and watercolors produced on location to create exquisite oil paintings of the landscapes that enthralled her. Her early work reflected the style of first-generation Hudson River School painters, including Thomas Cole, the movement’s founder, and Asher Brown Durand. Like these artists, Barstow strove to remain true to nature while imbuing her paintings with sublime light and balanced compositions suggesting the glorification of God. Her largest canvas, the 30-by-22-inch Landscape (in the Woods) (1865), depicts a calm, beautiful stream in the foreground and then draws the eye deep into a forest framed by inward-leaning trees and opening to patches of blue sky.

Landscape (In the Woods) | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 22 inches | 1865 | Scott Family Collection

In the mid-1800s, French painters led by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Charles-François Daubigny introduced a more romantic, moody style known as the Barbizon School, and Barstow incorporated aspects of this approach. Yet even when her imagery was softer and more diffuse, Siegel says, “She was always true to the colors in nature and to the types of trees, the horticulture. She was very specific to what she was seeing.”

Barstow’s evolving style responded as well to a post-Civil War desire for “parlor paintings,” smaller canvases to be shown off in the homes of those whose means reflected an economy recovering after the war. Americans were nostalgic for a simpler, more peaceful past, for serene landscapes seemingly untouched by progress or war. One of Barstow’s paintings, an intimate autumn scene titled Pool in the Woods (1885), was purchased by clergyman and abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher. Art historian Jennifer Krieger notes that Barstow’s works “feel grand and majestic, regardless of the scale.”

Early October Near Lake Squam | Oil on Canvas on Board | 23.5 x 20.5 inches, framed | 1886 | Lebanon Valley College Fine Art Collection, All that is Glorious Around Us: The Vesell Family Collection, Gifted by Hilary Peery Vesell

In 2010, Krieger, who owns Hawthorne Fine Art in New York City, co-curated with Siegel Remember the Ladies: Women of the Hudson River School at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site. It was the first-ever exhibition solely dedicated to the female Hudson River School artists. Although throughout her career Barstow’s art was praised, exhibited, and sold well, the Hudson River School style fell out of fashion between the First and Second World Wars. When male art historians began revisiting the movement in the 1970s, they focused only on male artists. For decades, Barstow and her female peers and their accomplishments were ignored.

Wooded Interior | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 22 inches | c. 1885 | Collection of Thomas and Marilyn Tolska in memory of Jenni Tolska | Image provided by Chelsea Restoration Associates, New York

“It was an oversight that needs to be corrected,” Siegel says, pointing out that Barstow was well-read, well-educated, undaunted by nature’s challenges, successful as an independent woman artist, and active in charitable organizations of her day. During her lifetime she influenced countless young women to become professional artists. “She demonstrated the importance of living a full, multidimensional life,” Siegel says. Underscoring this quality, she describes a visit Barstow made to the ruins of Pompei in Italy, at a time when Mount Vesuvius was erupting. In a letter, the artist recounted how she and her companions hiked up the volcano’s slope, walking rapidly because the soles of their shoes were beginning to melt. Yet at the edge of the steaming caldera, she took the time to cook an egg on the surface of hot rock. “Everything to her was magical and fascinating and an adventure,” Siegel says. “I still find her to be very inspirational.”

After 30 years of writing about artists and other creatives, Gussie Fauntleroy remains fascinated by the life experiences and soul that intertwine in an individual and emerge as art. She has written for national and regional magazines, newspapers, museums, and galleries, has served as a book and magazine editor, and is the author of four books on visual artists.

No Comments