29 Oct Timeless Beauty

One evening a few years back, friends of Linda Lillegraven stopped by for dinner. Earlier in the day, she’d been working on a landscape of rolling grasslands spooling out across many miles to the horizon and a somber, cloudless sky. The only indication of human contact with the land was a dirt road that flowed in from the lower right of her canvas and quickly disappeared into the valley. Lillegraven had painted this scene often over the 40 years she and her husband had lived in Laramie, Wyoming, but for some reason, this painting wasn’t working. It needed something; she didn’t quite know what.

Artemisia | Oil on Linen | 24 x 36 inches | 2024

After dinner, as her guests stood in front of that troublesome painting, Lillegraven turned to her friend Judy Knight, an author and historian for Laramie County, and said, “I love this road, but why is it so well maintained? It doesn’t go anywhere.” Knight explained that the road had been a bus route that took children to a rural school, but that the school had closed years ago due to declining attendance. Eureka! Lillegraven suddenly knew exactly how to finish the painting. “The next day, I stood up on that hill and waited until a big pickup with a stock trailer went by in a cloud of dust. I transformed the truck into a small school bus, which is what the painting needed: that basis of civilization, some indication of the people who live in these places.”

From the Hart Lane Bridge | Oil on Linen | 18 x 24 inches | 2025

Soft-spoken and unassuming, Lillegraven is part of a rare, authentic breed of artists who paint the great American West as it is, without fanfare or the need to embellish scenes with romantic versions of what might have happened here hundreds of years ago. And though her paintings are highly realistic, she never gives the viewer so much detail that they know what the painting’s about entirely. The School Bus is the perfect example. That little plume of dirt is not the first or even second thing you see, but once you do, your own mind is freed to wander into the scene and make it your own.

“That’s just how I’ve developed as an artist,” Lillegraven says. “I paint those subtle things and make you search for them. Then you get a feel for the history of the place.” Here she pauses for a moment, then says, “I never quite get over the feeling that I’m a stranger here. Just because my great-grandparents came to this country on a boat, that doesn’t entitle me to think that I’ve been here forever.”

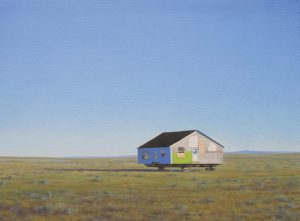

Migrant | Oil on Linen | 18 x 24 inches | 2017

How Lillegraven ended up in Wyoming and became one of the foremost painters of the West can be traced back to her dual love of art and science. “When I went to college as an undergraduate art major, the idea was that artists had moved beyond representational art,” she says. “We were going to do Abstract Expressionism because that was progress, and that was the only meaningful thing that artists could do. But I think, no. People have been creating representational paintings for at least 40,000 years, and I don’t think we’ve exhausted its potential. We need to address that duality of painting and life in the world, and there’s no reason to give it up.”

After graduating with a degree in art and a minor in zoology, she went on to earn a master’s in biology. But while hiking through the lonely landscape of northeastern Utah doing field research for a PhD, she realized that the life of a scientist was not for her. It was the summer of 1974, and she found herself staring out at a vast sea of barren land and thinking, “I don’t love science the way I love art.” And then, immediately on the heels of that thought came this one: “I need to learn how to paint great spaces like this, and somehow I’m going to do it.”

Science and art are essential partners in Lillegraven’s work. “Science has given me the tools to look at things and to know what’s going on,” she says. “I’ve used my scientific experiences all my life, especially the perspective of how the natural world fits together.”

Beyond the Mountains | Oil on Linen | 18 x 24 inches | 2023

When asked if she could paint anywhere, say street scenes in New York City, she says without hesitation, “No, not for very long. And I found that out when we went to Berlin in 1988.” Berlin is where Lillegraven’s husband, also a scientist, was sent for research. Fully expecting she would use this time to paint, she brought a projector and stacks of slides. “I was going to paint Wyoming, and I did a couple of paintings,” she says. “But then I realized that I couldn’t smell the sagebrush anymore.” Instead of forcing herself to recreate what wasn’t there, she shifted gears and spent the year visiting museums. That time spent studying past masters and interrogating their work provided invaluable lessons.

She also visited the Font-de-Gaume cave in France. “Those cave paintings are a great interest of mine and a huge inspiration,” she says. “They convinced me that there is no such thing as progress in art. Picasso, when he went through Lascaux, said, ‘We have learned nothing.’ And I agree.” She also recalls visiting a museum of antiquities and seeing a small, almost indecipherable carving on mammoth ivory. “I looked at it and thought, ‘Oh, I’ve seen that scene. It’s a bison swimming in a river.’ That carving depicted the world they lived in, and what surrounded them — they had all the skill in the world.”

Glory in Excelsior Geyser Crater | Oil on Linen | 20 x 20 inches | 2016

The concept of geologic time plays a prominent role in Lillegraven’s work. “I’m looking for timelessness in those empty landscapes,” she says. Shaking her head, she recalls being told that the early landscape painters came out West to paint the land as uninhabited and available for exploitation. “That’s not my motive at all,” she says. “I’m looking at it from the timeless perspective of the land itself. You know that inscription on the old engineering building at the University of Wyoming: Strive on—the control of Nature is won, not given?” she asks. “It’s just so awful in a way, the notion that man can subvert nature. My work is about this: We don’t control nature, and nature doesn’t care about us in the least. But it is sublime. That’s what I’m trying to express, that we should value it. And we need not pretend that we have conquered it.”

On 2000, Lillegraven won the Arts for the Parks Grand Prize. Her winning painting depicted a bend in the Yellowstone River within Yellowstone National Park. “There’s nothing much there except this grassy landscape with a river going through it,” she says, recalling something that happened the day after the exhibit opened. “I was walking through and noticed a man standing in front of my painting. And I heard him say, “I don’t get it.” Meaning, he didn’t understand why my painting won. And I thought, ‘Ha-ha! You don’t have to.’”

By now, Lillegraven is accustomed to this reaction to her paintings. “People look out across this land and think, ‘Well, there’s nothing to see here,’” she says. But this comment, she has come to understand, belies a sense of unease because there is entirely too much to see here. “There’s something profound that happens when you’re standing alone out in the middle of wide open space with not a tree in sight: Your brain says, ‘Oh dear, what will I do if the lions come?’ That feeling is often there in my paintings.”

The Past | Oil on Linen | 18 x 36 inches | 2024

In the long tradition of painting Western landscapes, Lillegraven sees various esoteric approaches. One, in particular, is like that of Albert Bierstadt, who employed his grandiose European training and aesthetic to wow the viewer, as if to say, ‘Look what I can do. Look at the skill I possess.’ “That’s what his paintings are about: his monumental skill,” Lillegraven says. “But I want you to feel that you could walk across the sagebrush. You can’t feel that if I show you every leaf, or if I reduce it to a single brushstroke. So, I’m somewhere in the middle of realism and abstraction and never quite sure whether I’ve got the balance.”

Although she has spent years painting throughout Wyoming and the West, Lillegraven primarily explores the land within a 30-mile radius of her home. “I do best when I’m painting things that are familiar to me,” she says. “If I try to work as a tourist, my heart isn’t in it. Besides, there’s so much variety right here: The light and land change dramatically from season to season.”

Mud Volcano Dawn | Oil on Linen | 24 x 36 inches | 2023

She is also decidedly a studio painter. “The things I like to do with the expression of subtlety in great spaces are things that you can’t do in plein air painting in an hour. So, I take a lot of photos, but mostly the images remind me of my time there. They bring back memories,” she says. “The more I work on the painting from my many photos of a place, the more I remember what was there. It’s never a question of copying photos, but of the interaction with memory and the landscape. I’m painting the memory of a limited moment.”

Lillegraven usually has five or six paintings in progress in her studio, explaining that if she gets a little stale on one, she’ll put it aside and pick up another. “But when they’re up on the walls, they’re talking to me,” she says with a laugh. “Every time I go through the studio, I’ll hear a painting muttering at me, and then one day, it’s worked enough on my subconscious that it’ll say, ‘You know, if you move this tree over two inches to the left, everything will balance.’”

Cows and Calves Near Antelope Creek | Oil on Linen | 24 x 36 inches | 2024

What makes the difference between ‘Ahh’ and ‘That’s boring’ in a painting, Lillegraven says, is something she navigates through with each painting. “It’s really an emotional reaction in my brain that works at some unconscious, albeit deliberate manner. It requires a great deal of thought and time,” she says. “Painting is always instinctive, in a way. I’m having this conversation with the painting, channeling the emotion and the memory until I’m back there, standing in that place and feeling the wind and hearing the crunch of gravel. All those memories work their way down into some subconscious level of my brain. So, if I haven’t been there, the painting would be dead.”

In that sense, this ancient, quiet land is like an old friend whose company Lillegraven never tires of. And like talking about an old friend, she says of her paintings, “I hope I’m showing people elements in the landscape that they’ve always seen but never noticed.”

No Comments