30 May Clyfford Still: A Western Painter?

BECAUSE HE IS ONE OF THE GREATEST ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST PAINTERS, Clyfford Still most often is considered an artist of the New York School. It was in New York in the 1950s where abstract expressionists such as Still, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Franz Kline thrilled the art world and changed popular culture with their revolutionary work and ideas. Still’s work consisted of large canvases of bold colors and jaggedly kinetic vertical lines, suggesting many forms but specifically depicting only the paint itself.

The movement is seen as quintessentially Big Apple, fueled by the city’s post-World War II rise as the world’s greatest cultural, intellectual and financial capital. Still developed his pioneering style in the 1940s and stayed with it until his death, never really explaining his work’s influences or symbolism.

But a new theory is being offered concerning Still, who died in 1980 at age 75. The West can claim him — the spirit, concerns and even imagery of the West can be seen in his art. He was born in Grandin, North Dakota, and moved early to Spokane with his family, who also had a farm in the southern Canadian province of Alberta. While he visited the East as a young man, he taught art at Western Washington State College in Pullman.

After working in war-related industries in San Francisco and then making his first breakthroughs in New York with his abstract expressionist painting, he returned to San Francisco in 1945 to teach at California School of Fine Arts. He moved back to New York in 1950 and never again lived in the West, going on to a Maryland farmhouse/studio in 1961.

“He spent the first 40-plus years of his life on the West Coast, and particularly his breakthrough works of the late 40s were done in San Francisco,” says Dean Sobel, who is director of the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver, which is scheduled to open in 2010.

This interpretation comes as fundraising for that $33 million museum has surpassed the halfway mark. Still’s will offered to bequeath 2,400 artworks, most never displayed previously, to any city willing to devote a museum solely to him. The cache also includes his archives and even a baseball glove. The search took decades, but Denver’s Mayor John Hickenlooper, elected in 2003, thought it would be a perfect match for a fast-growing Western city establishing itself as a cultural center. Still also had a nephew in Denver. The mayor made an agreement with Still’s wife, Patricia, who died in 2005. The museum is being designed by Portland architect Brad Cloepfil.

It also comes as the Denver Art Museum — which will be adjacent to the new Still Museum — has an open-ended (through most of 2008, at least) “sneak peak” show of 13 paintings from the Still Museum’s still-in-storage collection. Clyfford Still Unveiled chronicles how, in the 1930s, Still was moving from pictorialism toward abstraction with vertically oriented imagery either Western landscapelike in appearance or totemlike in the depiction of the human figure, as if influenced by Pacific Northwest Indians.

“You can certainly see [that] when his work became more abstract, he sort of goes through this totemlike surrealist phase, where there are lots of recognizable forms from Northwest Coast Indian art and, more broadly, primitive art,” Sobel says.

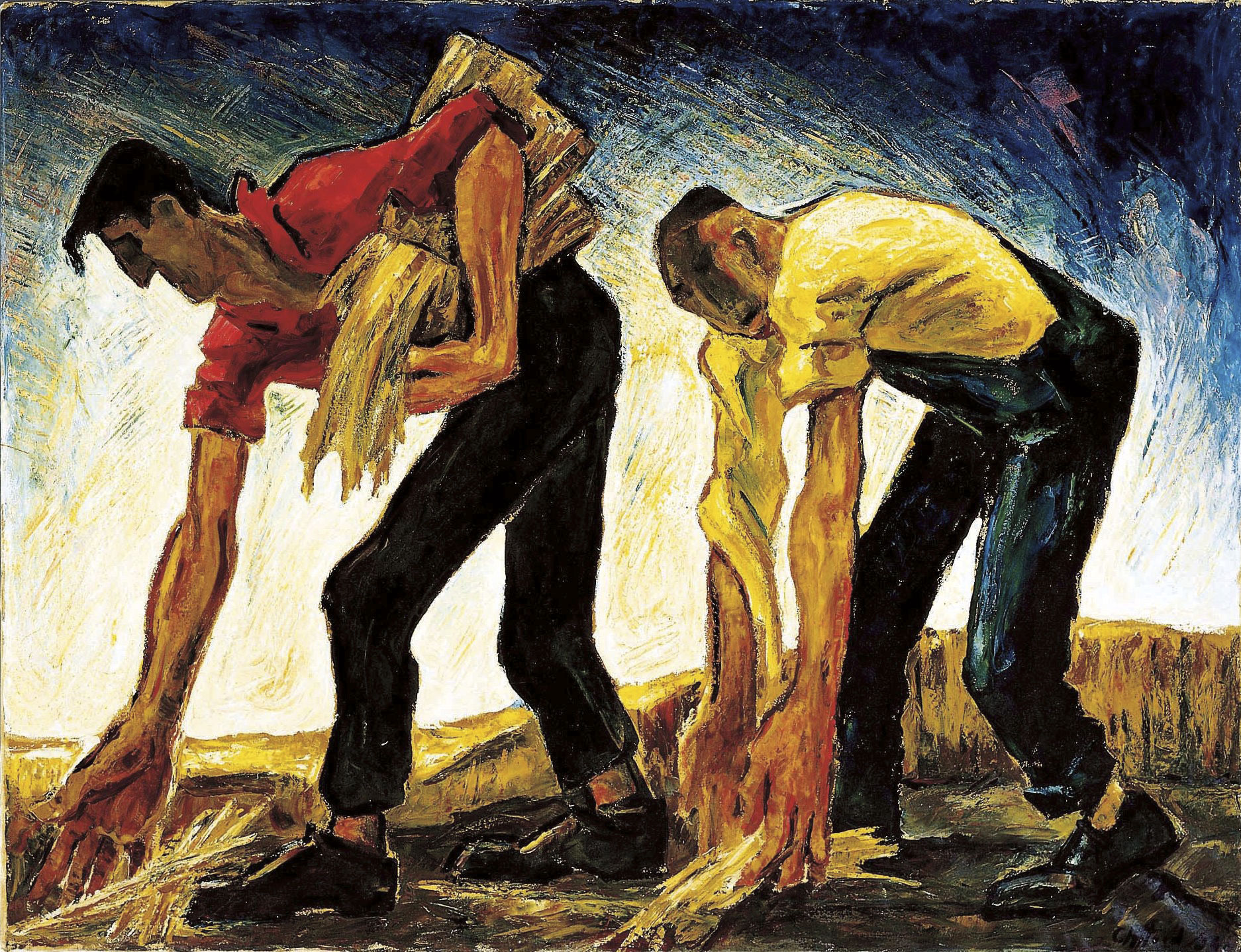

Lewis Sharp, director of the Denver Art Museum and an American art enthusiast, sees specific parallels between Still’s abstract expressionist work and some of the earlier paintings in the current show. In particular, he’s impressed by a 1936 Western painting, PH 77, in which two men in a field stoop over, long sharply outlined arms extended downward, to harvest wheat. One wears a bright red shirt; another yellow. “It almost catches your breath,” Sharp says. “You go, ‘My God, the same colors, same verticality of elements, the same application of paint to canvas.’ ”

This view of Still finds a skeptic in Doug Dreishpoon, senior curator of Buffalo’s Albright-Knox Art Gallery. That museum holds a spot of critical importance in Still’s career, hosting a retrospective of his work way back in 1959 after buying a key abstract expressionist work, 1954. Still later gave the museum 31 paintings, making it a key public repository for his work. At different times, Dreishpoon says, Buffalo considered seeking the Clyfford Still Museum. (So, says Sobel, did Fargo, North Dakota; San Francisco; and Orange County.)

“I think it would be somewhat unfair to draw a direct connection between Still and the West,” Dreishpoon says. “It’s fair to say wherever someone comes from or spends time in may bleed through to their creative process. But there are so many factors to consider that in some way it denatures the metaphorical potential of the work to draw a direct connection.”

That painting, 1954, with its dramatically eruptive bursts of crimson, black and white, was loaned to a 2006-2007 exhibition organized by Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, called The Modern West: American Landscapes, 1890-1950. Other works in the show were by such painters as Marsden Hartley, Thomas Hart Benton and Georgia O’Keeffe. (It traveled to Los Angeles County Museum of Art.) Amid their landscapes, the abstractions of 1954 could indeed seem evocative of canyons, mountains, lightning bolts or the earth ripping apart from a quake.

Still’s work, as well as Wyoming-born Jackson Pollock’s, was part of what the exhibition’s curator, Houston’s Emily Ballew Neff, calls the show’s “epilogue,” after its stated time span had been covered. “We were not calling it a landscape painting, but said we can talk about how the artists distilled the memory of the American Western landscape, and how it played a role in the development of their specific visual language,” she says. “But if you try to be literal, it doesn’t really work. The artists are using landscape as a kind of metaphor.”

Still was an iconoclast with a reputation for argumentativeness and an intense dislike for the business of art — which is why he left New York for Maryland. He even disdained descriptive titles for his paintings. Fiercely American, he once wrote that New York’s famous 1913 Armory Show, which introduced 20th-century modernism to the American art world, represented “sterile conclusions of Western decadence.” Influential curator Katharine Kuh, in her book My Love Affair With Modern Art, titled her chapter on Still, “Art’s Angry Man.”

Careful not to label Still as any specific kind of painter, Kuh, who died in 1994, nevertheless saw something of the West in his work. In her introduction to a 1979-1980 retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, she wrote: “His paintings evoke the West, not, to be sure, in appearance, but in feeling. Larger than life, liberated, hard, even harsh, they embrace new frontiers.”

Sharp, who worked at the Met as a curator of American paintings and sculpture at the time, considers himself lucky to have met Still. “I got to walk through the gallery any number of times while he was installing it and met him on one occasion,” he says. “It was the first time I had encountered a major contemporary artist and I fell in love with the works. So for them to end up in Denver is extraordinary.”

- “1936, PH 77” | Oil on Canvas | 43 x 56 inches | © The Clyfford Still Estate, Photo: Peter Harholdt

- “1957 J No. 2, PH 401” | Oil on Canvas | 113 x 155 inches | © The Clyfford Still Estate, Photo: Peter Harholdt

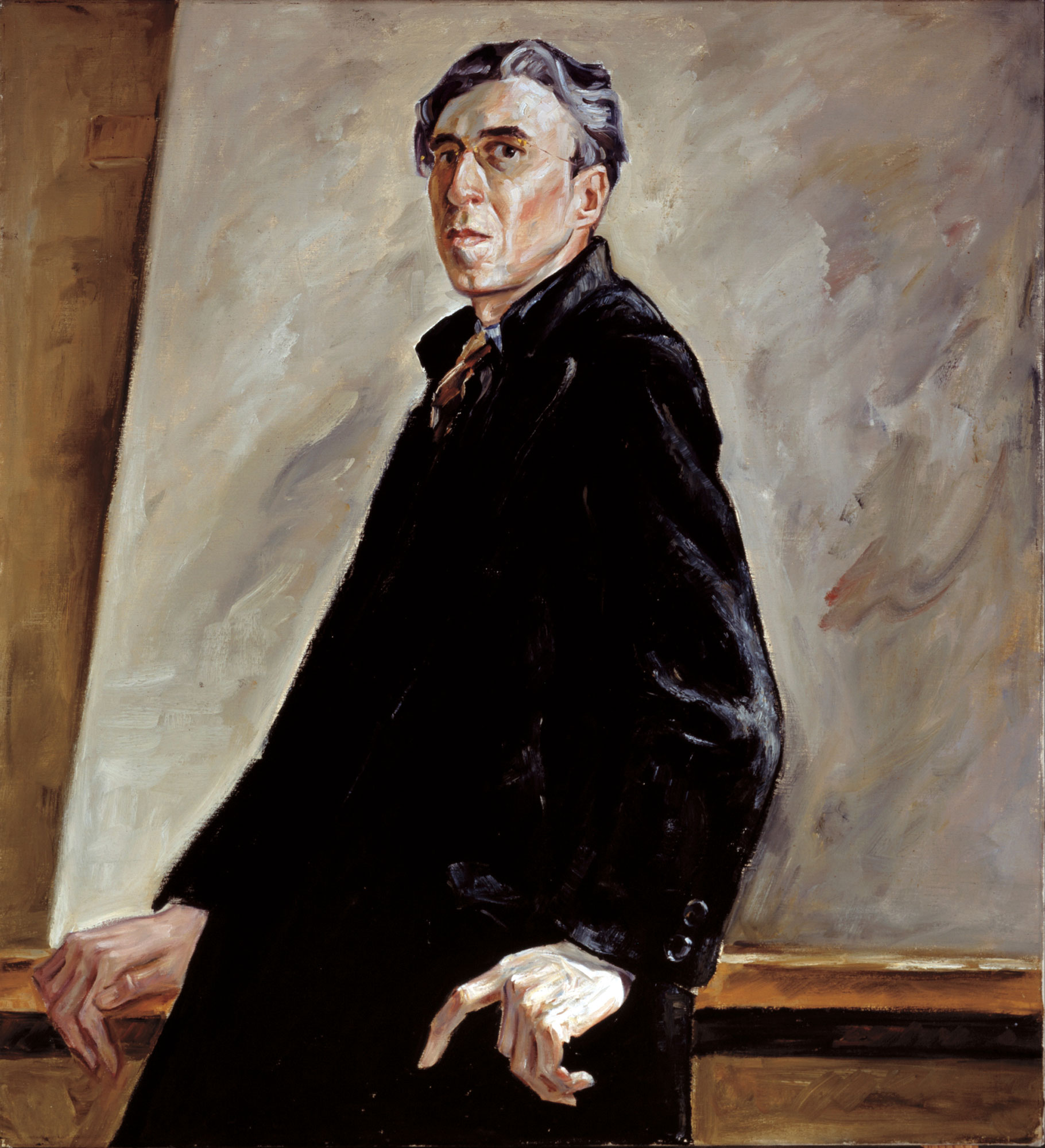

- “1937, PH 343” (Detail) | Oil on Canvas 45 x 35 1/2 inches | © The Clyfford Still Estate, Photo: Peter Harholdt

- “1940, PH 382” | Oil on Canvas | 41 x 38 inches | © The Clyfford Still Estate, Photo: Peter Harholdt

- “1938 No. 2, PH 297” | Oil on Canvas | 33 x 25 inches | © The Clyfford Still Estate, Photo: Peter Harholdt

No Comments