29 Oct Revelations

Like many sculptures Pati Stajcar creates, her recent work titled Seascapes did not start with a specific concept but rather with the material itself: a chunk of red cedar burl, a knobby growth on tree trunks that loggers cut away because its dense, swirling grains make it unsuitable for lumber or shingles. Stajcar, however, finds plenty of inspiration in such discards. “When my brother-in-law lived in Washington state, he used to collect them for me,” she says. “And my husband Dave and I would drive up there from our home in Golden, Colorado, load a trailer, and bring them back.”

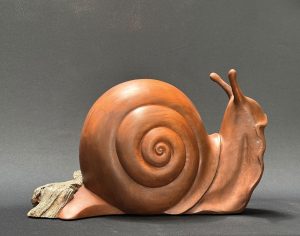

Aesop’s Fable, Bronze, Edition of 9, 21 x 25 x 18 inches

Stajcar, who works in bronze and stone, as well, says that this particular piece of burlwood — long, narrow, and tapered — spoke to her of ocean waves. As she sat with the wood, forms began to reveal themselves in its rippling burl patterns. She sketched them out first in pencil on paper and then directly onto the wood’s surface with chalk pencils. Gradually, she established the lines by which she’d carve. That sculpture debuted at the 20th annual Quest for the West Art Show and Sale at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Duckhorn Pond, Marble, 14.5 x 24 x 14 inches, photo: Mel Schockner

While many sculptures can be appreciated from all sides and angles, a careful walk around Seascapes offers rich rewards. On what appears to be the front of the sculpture, a bronze disc, patinated to a dusky gold like a setting sun, is inset into polished cedar swirls that evoke rolling waves, with their forms adding new meaning to the burl’s grain. “And then, on the other side,” says Stajcar, “I just followed along with the wood’s ‘waves’ and I put a little turtle at the narrow end.” That turtle is a delightful surprise and a poignant reminder of the need to maintain a fearless spirit amid nature’s immense powers.

Aristocrat, Red Cedar Burl, 63 x 22 x 15 inches

Equally satisfying is the fact that Stajcar left the larger end of the sculpture polished but otherwise unfinished. “When I’m working in wood or stone, I do try to leave a little bit of the material in its original form, just to show you where it came from,” she says.

But for all of Stajcar’s philosophical reflections, she’s quick with a one-liner reality check like this one: “At shows, we sculptors like to joke that our works are what people back into when they’re looking at a painting.” With that same humble and generous spirit, she welcomes viewers to touch her sculptures. “Unless it’s so fragile it might break, I love when people want to touch my sculptures. Each piece has a rhythm, especially when you’re running your hands over it. I tell people who ask to go ahead and touch it, and tell me how it makes you feel.”

Growing up in Norristown, Pennsylvania, a northwestern suburb of Philadelphia, Stajcar says art always made her feel at one with the world. “I think I drew before I wrote,” she says. “And I wrote very early. Even in kindergarten, I remember the other kids asking me to help them draw something — a horse’s head, a woman’s face — because they liked the way I drew.” She smiles at the memory. “I gotta tell you, I wasn’t that good. Okay? But I loved it. People may say you’ve got a God-given talent. But it wasn’t just given to me. If you ever saw some of my earliest drawings, you’d know that. But I really worked hard at it.”

Seascapes | Red Cedar Burl | 8.5 x 31 x 6.5 inches

By the time she entered high school, her dedication had grown even stronger. “I got all my credits done early for math and English and gym, so by 11th and 12th grade, art classes were pretty much all I took,” she recalls. “Our art teacher would encourage us to go outdoors and draw whatever we wanted, and I always gravitated towards the animals.

Nevertheless, after graduation, art took a back seat — or, more fittingly, a jump seat — to her desire to start earning money. She enrolled in a specialized trade school focused on careers in the airline industry and, after completing the course, was hired by a small regional airline in Florida. “We flew to Kissimmee, Miami, Tampa, and the Keys. I don’t think our old prop planes ever went over 3,000 feet; you could have skydived from them.” Two years later, she moved to Denver for a reservations job with Frontier Airlines. “That’s where I met the love of my life, Dave Stajcar, a mechanic with the airline,” she says. “And I spent the next eight years working for Frontier.”

Throughout her time at Frontier, Stajcar kept creating art, mainly small portraits in pastels or watercolors, to earn a little extra money. In the late 1970s, Dave introduced her to his coworker Mike Balas, who happened to be a wood carver, specializing in work so detailed that she says, “If you blew on his carving of a feather, you would think it was going to move like a real one.”

Slow Roll | Red Cedar Burl | 13.5 x 23 x 10 inches

Intrigued, she took carving lessons from Balas for four years, after which he asked her to join him in teaching. By 1985, Frontier Airlines was struggling and offered buyouts to any employees who wanted to leave. So, Stajcar took the money and jumped into sculpting full-time. She started entering her work in the Ward World Championship Wildfowl Carving Competition & Art Festival, and in 1990, her carving of a great horned owl, titled Death Watch, won third place for interpretive sculpture at the prestigious World Level. “Once I turned that corner,” she says, “there was no looking back.”

Stajcar specialized exclusively in wood for the first five years. Then, in July 1989, she attended her first MARBLE/marble sculpture symposium, held in the Colorado mountain town aptly named Marble, for its rich deposits that provided the stone for such national landmarks as the Lincoln Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. That’s where she met renowned stone and bronze wildlife sculptor Gerald Balciar. “I saw his work ethic, and he could see how I worked. And I told Jerry, if he ever wants an apprentice, not a student, but an apprentice, please call me.” On New Year’s Day 1990, she was surprised when Balciar called, offering a position assisting in his studio in Arvada, just half an hour away from her home.

For the next two years, Stajcar worked for and learned from Balciar, putting in at least 40 hours a week. “That’s where I learned everything about sculpting in marble and bronze,” she says. “I was even doing the welding, chasing, and polishing. And he would let me use his big studio space for my own projects.”

Migrants | Red Cedar Burl | 21 x 10 x 5 inches

She started entering national sculpture shows and building her resume with memberships in the National Sculpture Society, the Society of Animal Artists, and Allied Artists of America. Her work ethic went from strong to relentless. “Art is a business,” she states matter-of-factly. “People sometimes say to me, ‘Oh, you’re an artist. You can work whenever you want.’ And I say, ‘Yeah. I can work the first 12 hours of every day, or the second 12 hours, whichever I like.’” Her natural talent and professional training combined with dedication have brought many national awards, of which she says, “My gosh, those just take the wind out of me, really. It is just amazing to me that someone thinks a piece I did should take top honors.”

Red Rover | Bronze | Edition of 9 | 94 x 38 x 25 inches

Recent works by Stajcar speak volumes, whether in wood, stone, or bronze, and firmly establish her among the top artists in her chosen field today. Another piece at the 2025 Quest of the West Show, Slow Roll won the Cyrus Dallin Award for Best Sculpture.

Dawn and Dusk | Marble | 51 x 24 x 7 inches

An additional excellent example is Dawn and Dusk. Starting with a vertical slab of rosy-hued marble more than 3 feet tall, the artist fashioned an elegant representation of the circle of life, with two doves perched on opposite ends of a gently curving central opening in the stone. The stone itself stands on an understated wooden base she designed and carved as an abstracted silhouette of a mountain range, giving the piece a monumental feel. Dawn and Dusk is one of the few sculptures she intentionally designed to be displayed against a wall, as she left its backside as a flat, unfinished rock. “For some reason, this just spoke to me that way.

Bird’s Eye View | Bronze | 24 x 6 x 4 inches

Working in bronze requires Stajcar to employ a different set of skills. Where sculpting in stone and wood involves a subtractive process of grinding, chipping, carving, and sanding to uncover the artist’s vision, bronze, on the other hand, is an additive medium. A sculpture is first built in clay or another modeling compound to form the three-dimensional form, from which casts and molds are made, and the molten metal is poured. The results of such labor can possess powers to astonish, whether in size or shape.

For example, Bird’s Eye View, another piece that debuted at the recent Quest for the West, appears to defy gravity despite its heavy medium — a single life-sized chickadee rests atop a long, graceful reed that gently bows under its weight. “You could just sculpt a bird and plop it on a base,” Stajcar states. “But design, flow, and balance matter to me.”

Triangulation | Bronze | Edition of 5 | 117 x 39 x 70 inches

Indeed, these qualities and the deeper meanings they convey are at the heart of what Stajcar aims to achieve. “Her works have a timeless presence that resonates deeply with our clients,” observes Bekka Saks, owner of Saks Galleries in Denver, which has represented the sculptor for nearly 35 years. “There’s often a moment of quiet awe when someone first encounters her sculptures because she captures the essence of life’s most meaningful experiences — grief, joy, transformation — through elegant form. There’s an organic flow to her pieces that reminds viewers of their own connection to the natural world.”

The artist herself is moved not only by the subjects she portrays but by the people who welcome her works into their personal collections. “It touches me,” she says. “It says that I did something that matters to them. I hope that what I created goes forward in a positive way and makes the person who bought it feel what I felt when I made it.”

No Comments