12 Jan The Eyes Have It

TRUTH BE TOLD, Glenna Goodacre broke the mold the moment the tenacious artist bucked the advice of her sculpture professor at Colorado College, who suggested she forgo pursuing a career in sculpting because of her inability to visualize in 3-D. Instead, Goodacre realized her artistic talent and, in 1996, having already secured her legacy as one of the world’s most revered sculptors, the Lubbock, Texas-born artist returned to her hometown to deliver a commencement address at Texas Tech University that she titled, “Success is the Greatest Revenge.”

How sweet Goodacre’s triumphs have been. She began her career as a portrait painter until 1969 when she molded a chunk of sculptor’s wax given to her from gallery owner Forrest Fenn. Using a nail and hairpin, she created a 7-inch-tall bronze sculpture, called Ballerina, that was modeled after her daughter, Jill. Since then, Goodacre’s hands took to clay like “a duck to water.”

By taking advantage of her pioneer toughness inherited from growing up in West Texas, the 77-year-old Goodacre, who moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1983, has crafted more than 600 different works during the last 50 years. But after years of soaring high, the academician of the National Academy of Design has methodically chosen to clip the wings of her illustrious career by destroying all the molds for existing editions and not creating any new works.

“After Frederic Remington died, Roman Bronze Works in New York just kept casting his bronzes for years,” says Goodacre, who used to keep her awards hanging in the studio bathroom as a reminder to never rest on her laurels. “Now people don’t know what they’ve got when they own one of his pieces. I want to make sure there’s no question with my work, so I’m retiring and so are my molds.”

Auctioning the works of acclaimed artists is ordinarily a posthumous observance, but Goodacre — the face behind Glenna Goodacre Boulevard in her birth town — has steadfastly remained “not typical of most anything.” Instead, she is doing something completely unique in American art, according to longtime friend Jack Morris, a founding partner of the Scottsdale Art Auction. Approximately 120 lots of Goodacre’s remaining private collection, including Ballerina, will be sold on April 6, 2017. Having gained the respect by many as America’s Greatest Living Sculptor, she’s earned the right to “do what I want to.”

As a precursor to that divestiture, Goodacre has already given away her sculpting tools, hundreds of pounds of clay, sculpture stands and her art books to the New Mexico School for the Arts, a state-chartered Santa Fe high school with an arts-focused curriculum.

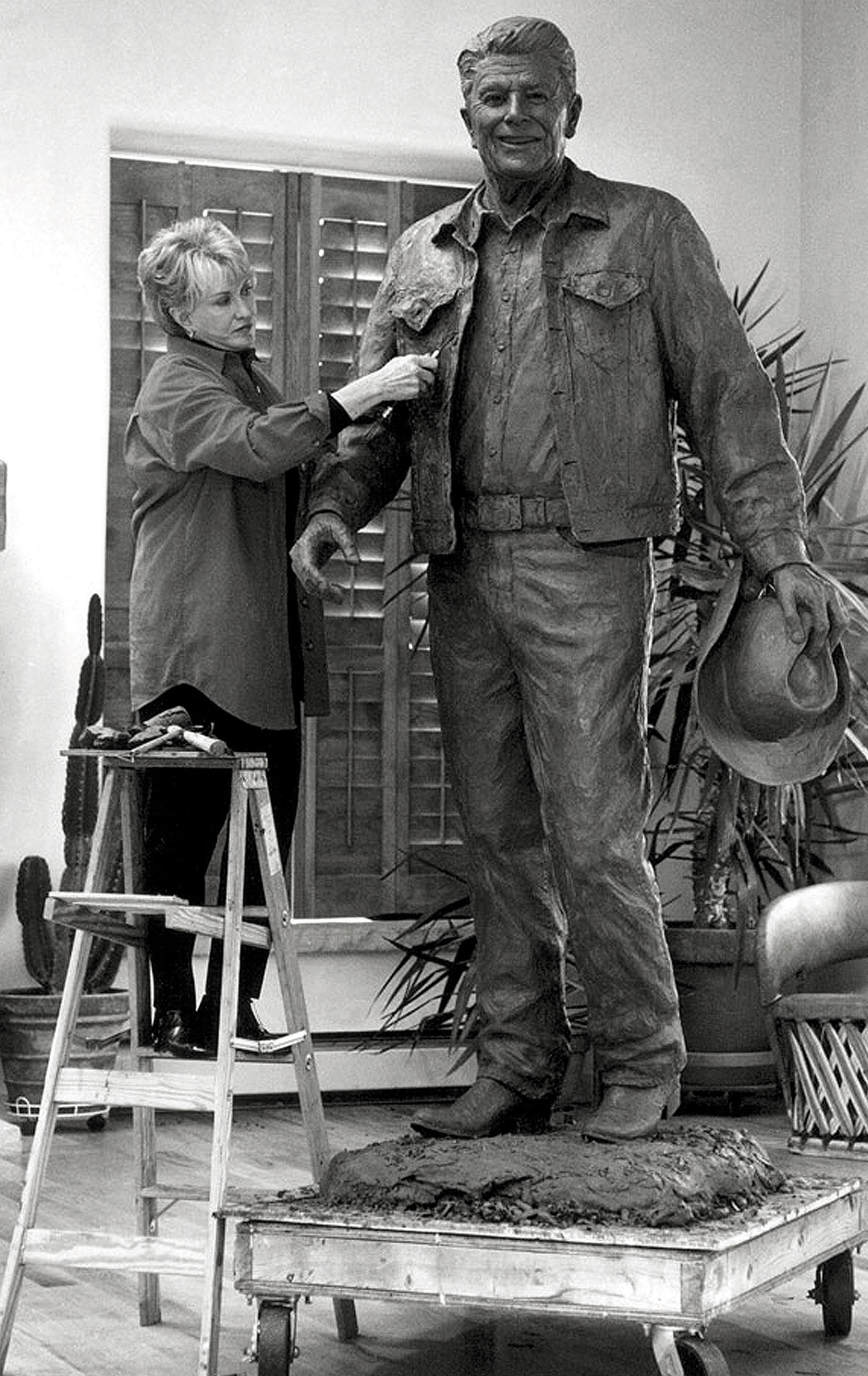

To understand the constancy of Goodacre’s sculptures, inspired by the works of Michelangelo [1475–1564], Jean-Antoine Houdon [1741–1828] and Auguste Rodin [1840–1917], it is imperative to gaze into the eyes of her creations. Over the years, Goodacre has depicted the character and emotions of her subjects, which range from children to Native Americans to actors and U.S. presidents. “I am a people sculptor and my pieces speak to people,” says the down-to-earth Cowgirl Hall of Fame member. “I learned from other artists and from the foundries in Loveland, Colorado, how to make the bronze convey my ideas with surface treatments and patinas.”

She is also able to convey her ideas in any size. There’s the monumental 14,000-pound, 12-by-40-foot Irish Memorial (2003), consisting of 35 life-sized figures located near Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the 7-foot-tall Vietnam Women’s Memorial, erected in 1993 on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., down to a collectible piece of work so tiny it fits in a pocket.

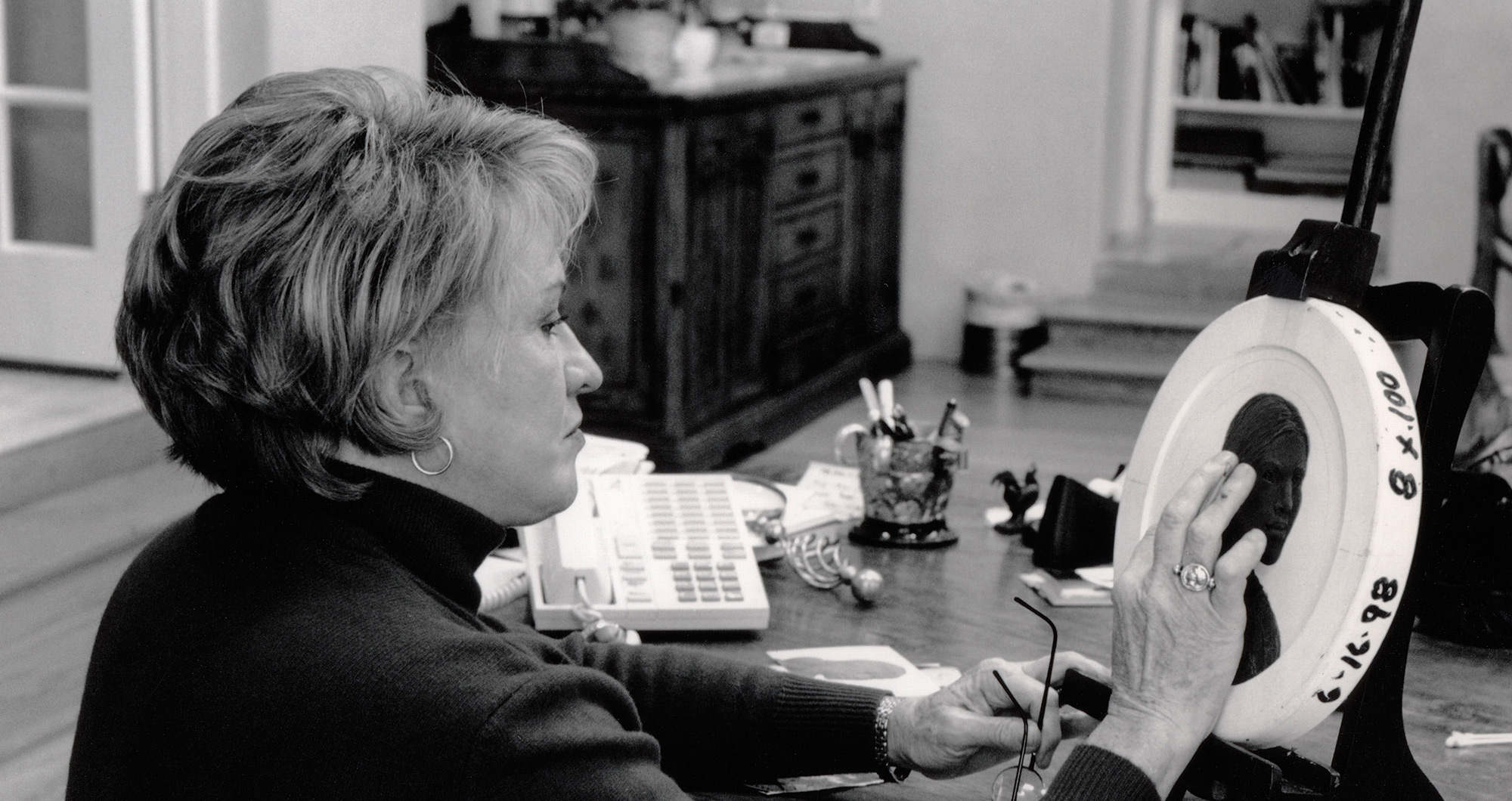

In 1998, Goodacre was one of 23 artists who submitted 121 renditions to the U.S. Mint to design the obverse of the Sacagawea dollar coin. Of the six finalists, five of the designs were hers; the one chosen, depicting a Shoshone Indian woman carrying her baby, became Goodacre’s smallest work and largest edition to enter circulation in 2000. At Goodacre’s request, the $5,000 commission payment was made in the form of her own dollars.

“Two Mint guards brought the 5,000 coins to my studio in Santa Fe and, at the time, I didn’t know how special they were, but some have sold for as much as $1,500 each. I gave some to my grandchildren, kept one for myself and sold the rest. I believe they go for around $500 now,” Goodacre says.

Daniel Anthony, her manager since 1987, revealed the bronze that practically became a trademark for the artist, Puddle Jumpers. Completed in 1989, it depicts six children, three of which are airborne, and is Goodacre’s most expensive piece, selling for $350,000. Regardless of price, art collectors around the world have wisely invested in Goodacre’s sculptures, including one of her Santa Fe neighbors, Kevin Rowe. “We love Glenna’s depiction of Sacagawea, who was crucial to the success of the Lewis and Clark expedition,” says the owner of the 26-inch Shoshone Mother (1999) and the nearly 7-foot Sacagawea and Jean Baptiste (2001).

Goodacre’s life is one that could not have been scripted. And while it’s sometimes difficult for an artist to recognize when a piece of work is complete, this creator is dropping the curtain on her celebrated professional career to craft a new personal chapter through her grandchildren’s eyes.

- Glenna Goodacre working on the final design for the Sacagawea dollar in 1998. Photo: Daniel Anthony

- “River Woman” (detail) | Bronze | 48 x 30 inches | 1989 | Edition of 25 | Photo: James Hart

- “Shoshone Mother” | Bronze | 26.5 x 12.5 x 14.5 inches | 1999 | Edition of 40 | Photo: James Hart

- “Torso in Motion” | Persian Travertine | 32 inches tall (excluding base) | 1998 | Photo: Dan Barsotti

- “Famine” | Bronze | 13.25 inches tall | 1998 | Edition of 25

- “Spotted Tail” | Bronze | 10 feet x 10 inches | 2012 | Edition of 5

- Glenna Goodacre in her Santa Fe, New Mexico, studio working on “After the Ride,” a tribute to former President Ronald Reagan. Photo by Daniel Anthony.

- “Peter” | Bronze | 20.25 inches tall | 2002 | Edition of 25

No Comments