04 Sep Between Truth and Tale

Thom Ross may be best known for his bold, stylistic artwork. At his core, however, he is a historian — a storyteller driven not by myth but by a deep desire to understand and reinterpret it. For Ross, creativity is a tool for unearthing truths buried beneath centuries of legend. Nowhere does this vision come to life more vividly than in his ongoing exploration of the American West.

Modoc Playing Croquet | Acrylic on Canvas | 36 x 36 inches

To Ross, the West is the stage upon which the first great American myth unfolded. It’s a region steeped in cultural memory, often depicted in broad strokes of heroism, villainy, and Manifest Destiny. However, Ross argues that these portrayals have flattened complex individuals into caricatures, repeating the same narratives so often that we forget to question their accuracy.

“When people ask me about Custer’s famous last fight, I have to ask them if they want to talk about Custer’s Last Stand or the Battle of the Little Bighorn, two names for the same fight: one mythical and one historical.”

Billy the Kid Playing Croquet with the Sun and the Moon Still in the Sky | Acrylic on Canvas | 36 x 36 inches

He wants his artwork to be thought-provoking and to challenge our preconceptions about a region that’s so easily susceptible to romanticization. Ross is drawn to what he calls the “historical folk hero” — real people like Davy Crockett, Billy the Kid, and George Custer, whose lives became symbolic tales retold across generations. He aims to complicate the legend — to open a space for nuance, ambiguity, and overlooked realities. He paints such legends layered with historic context that he’s extensively researched. In place of glorified cowboys and noble frontiersmen, Ross gives us Native Americans playing ping-pong or croquet, and General Custer leaving Appomattox Court House after the surrender of the Confederate Army with a table balanced on his head. These surreal, often humorous juxtapositions are not random; they are rooted in real, if lesser-known, historical accounts. They jolt the viewer into a new awareness, compelling us to ask: What else have we missed?

A Crow woman visits Thom Ross’ 2005 installation at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in Montana. She stands next to the artist’s depiction of Buffalo Wallow Woman, one of four women who rode into battle to fight General George Custer and the 7th Cavalry.

“Don’t tell me that there’s something romantic about cowboy life,” Ross says, recalling his cousins’ realities of managing livestock and resources to maintain a profitable ranch. “This Western notion is all based on this myth.”

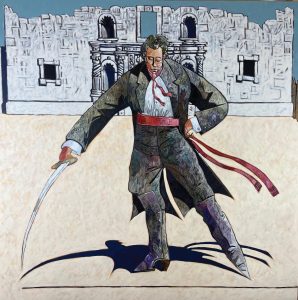

Born in 1952 in San Francisco and raised in Sausalito, California, Ross grew up entranced by Western pop culture from Hollywood, like the TV shows “Bonanza” and “Maverick” or the movie “Once Upon a Time in the West.” Such early interests took on personal resonance: “I am basically the same little boy I was 70 years ago,” he says, recalling that he drew the Battle of the Alamo every day at school.

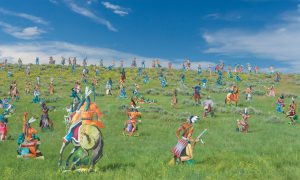

Each of the 200 slightly larger-than-life plywood figures was based on a person on the battlefield on June 25, 1876. The work was installed at Medicine Tail Coulee for five days before traveling to two other locations. Photos: Patrick Bennett

But a significant turning point came in 1976, when he attended a centennial observation for the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Ross found himself in the midst of a tense battlefield, torn between American Indian Movement protestors and pro‑Custer sentiment, including Custer’s own great-nephew.

After the ceremony, he lingered with his brother and a few friends beside the memorial. They were alone when a frigid wind blew across the landscape — a haunting gust that tipped over a wreath resting on a mass grave, making it undulate as if calling the dead to rise. “The buffalo grass was blowing insanely, as if hundreds of horsemen were riding through it,” Ross recalls. This “metaphysical epiphany” reframed Ross’ vision: History was not a static scene, but a story we tell ourselves — with ghosts shaking in the grass long after the facts fade. The moment planted a seed that would grow into his lifelong mission: to dismantle the oversimplified myths of the past and replace them with something more truthful, more complex, and more human.

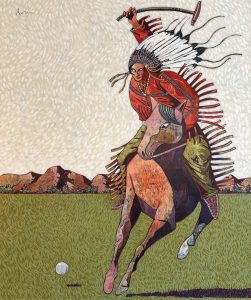

Polo Player | Oil | 72 x 60 inches

In 2005, Ross brought his experience full circle, installing 200 slightly larger-than-life plywood figures at Medicine Tail Coulee, at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in Montana. Each figure represented a real person. Notably, neither Native American warriors nor military soldiers were depicted as dead; Ross reconstructed the battle not as a scene of brutality, but of enduring presence. “This is because they never die,” Ross explains. “I don’t care what side you’re born with: good, bad, doesn’t matter. These guys are all immortal.”

The artwork struck a chord. At dawn one morning, about 70 Lakota and Cheyenne horse riders charged into the tableau, their quirts flicking at the wooden soldiers, their horses slipping in the dew. Ross recalls, “As soon as it’s installed, it’s out of my hands … people are going to react, and they want to react.” The installation was placed on the battlefield for five days, then exhibited in Sun Valley, Idaho, and Jackson, Wyoming, for six-day periods.

Custer and the Table | Acrylic on Canvas | 72 x 48 inches

“There are two aspects of the same thing: Custer’s Last Stand is the mythic tale that we tell in art and movies. The Battle of the Little Bighorn is what actually happened. This is the duality of everything,” Ross says, adding, “What you realize is that Custer’s Last Stand — that’s absolutely not the last stand that’s ever happened in world history. It’s one of hundreds. I have found the Battle of the Alamo in 1600 outside of Kyoto, the battle of Fushimi Castle. … Both battles lasted a similar length of time. Same outcome. The stories differ according to age and culture, weaponry, all this stuff, but the story stays the same.

“But what does it mean? What does the Alamo mean? What does the O.K. Corral mean? What does Billy the Kid mean? These are all minor things, but they’re known around the world. They made a ballet in 1938 for Billy the Kid. They still dance it today,” Ross adds. “They symbolize greater human experiences; a higher truth exists within the myth.”

Ross’ work spans painting, illustration, and immersive installations. He says the medium he uses depends on the story he wants to tell. He has illustrated more than 20 books, including Gunfight at the O.K. Corral: In Words and Pictures, and has contributed writing on baseball alongside authors like Stephen King and Doris Kearns Goodwin. Paintings like The Alamo (2000), Burial at Sea (1999), and Hickok and Cody (1998) reside in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Whitney Western Art Museum. His large-scale installations also include 154 Nevermore, a flock of plywood ravens posted on a highway outside of Jackson, Wyoming, and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a life-sized remake of a 1902 photo on Ocean Beach, San Francisco, which included 108 figures.

Burial at Sea | Mixed Media | 62 x 50 inches

One of his early major works, The Catch (1984), was a diorama for the Baseball Hall of Fame that immortalizes Willie Mays’ iconic 1954 World Series catch. Ross’ love of baseball rivals his love for the West, as both are landscapes of legend, populated by larger-than-life figures often reduced to highlight reels. “If you don’t like baseball and you throw it out, that’s your loss, not mine,” he says. “If you understand it, it has the same hidden power. It has the same heroism, the same ghosts.”

Ross’ paintings flatten space and employ broad planes of color. Figures are stylized, set against monochromatic backdrops, and painted with an expressive hand that lends movement and emotion. His scenes are drawn from overlooked facts, infused with a humanism too often missing in traditional portrayals of historical Western icons. His work disrupts our expectations to remind us that people, not caricatures, lived history.

Travis Draws the Line | Acrylic on Canvas | 60 x 60 inches

Ross is a meticulous researcher, often diving deep into the biographies and obscure stories of historical figures who captivate him. One of his latest series explores themes surrounding Billy the Kid, the famed New Mexican outlaw, for Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West. In The Resurrection of Billy the Kid, opening October 4, Ross’ work joins Bob Boze Bell’s and Buckeye Blake’s to demonstrate that the outlaw died young, but wouldn’t stay buried.

Now based in Lamy, New Mexico, the artist sees no division between his life and his work. From his boyhood drawings of the Alamo to his large-scale installations, he’s never stopped following the stories that first captured his imagination. “I didn’t become an artist to be an artist,” he says. “I became an artist because I wanted to tell stories. And those stories still animate me.”

Thom Ross’ 2008 installation at Ocean Beach, San Francisco, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, recreates a famous photograph taken there in September 1902. A surfer walks through the line of 108 painted plywood figures. Photos: Patrick Bennett

Through his art, Thom Ross is not only reframing the legends of the American West — he’s also reminding us that history is a story we are still choosing to tell. Through his unconventional depictions, he restores depth to figures who have long been flattened by legend. In doing so, he invites us to see the American West not as a finished story, but as a narrative still unfolding — one that is richer, stranger, and far more human than we’ve been led to believe.

No Comments