04 Sep Michael Scott: Visions of Fire, Ice, and Extinction

In early July, a fire began near the North Rim of the Grand Canyon — a fire that grew so hot, it created its own weather system. Relentless dry winds fueled what would become a “megafire,” casting superheated clouds into the sky that towered over the land with smoke columns visible for hundreds of miles.

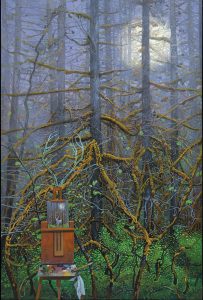

Paradise Lost | Oil | 57 x 76 inches

Nearly a decade earlier, artist Michael Scott was driving the road to the North Rim, while around him a smoldering fire created an eerie, otherworldly scene.

“You’re trapped with this idea of fire,” says Scott, a narrative painter based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, who has spent his career observing climate change and then returning to his easel to unpack the experience. Such natural forces inspire his paintings, which are invented from the world around him and swirl with dream states to reveal these smoldering paths: part imagination, part brutal reality.

“I don’t want to scorch and burn the viewer, but there is certainly a conversation that I want to participate in,” says Scott of his paintings, some of which are upwards of 10 feet tall. “I don’t browbeat the viewer into any submission — I give just enough clues and meanings that they can look at something with their own histories and their own imagination as to the outcomes.”

Origin of Species | Oil on Linen on Panel | 120 x 120 inches

A lifelong resident of the Midwest and Southwest, Scott’s artwork reflects on natural disasters and the erratic responses of a warming planet.

Born in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1952, he studied painting at the Kansas City Art Institute. After graduating in the late 1970s, he went on to earn a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Cincinnati in Ohio. His work gained momentum during graduate school, and he exhibited his landscape paintings in New York City, laying the groundwork for a career that has included exhibiting artwork for more than 40 years. Today, his paintings reside in the permanent collections of the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio; the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi; the Tia Collection in Santa Fe, New Mexico; the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles; the Whitney Western Art Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center for the West in Cody, Wyoming; and many other institutions.

Many of Scott’s paintings are devoid of people. Instead, the landscapes and animals emerge as metaphors: the soaring firebird, polar bears lamenting the destruction of their habitats, the ghostly outlines of a deer, wolf, or owl, always watching.

“Standing in front of these paintings — they are epic, gigantic works,” says Kathrine Erickson, of Santa Fe, New Mexico’s EVOKE Contemporary, which represents the artist. “It’s like you’re with the polar bears.”

Messenger of the Bitterroot | Oil on Canvas | 58 x 87 inches

Scott describes such creatures as omens, appearing within the magnificent and changing worlds he paints. In Firebird Fin, a feathered phoenix soars above volcanic eruptions, lava flowing below, while detached ice sheets float in the foreground. In other works, such as Origin of Species and Rogue Wave, there are vehicles of survival — a broken canoe or lifeboat — that may or may not carry the viewer to the other side.

“We are part of the natural world. You may not want to address it, or you may not want to admit it, but that’s reality. And it’s something that I’m fascinated by in my own lifetime,” says Scott. “I use the natural world as an exercise in looking at my own life and the struggles that I have.”

From Scott’s paintings emerge the elemental building blocks: earth, fire, water, and air. His artwork can take years to manifest, as Scott waits for the essence to emerge. “There’s not an immediate answer,” he says. “It ruminates, and I allow that kind of percolation to bubble up over a block of time.”

The Melting of the Ice Cave | Oil on Linen on Panel | 56 x 78 inches

In the 1980s, while living in the Ohio Valley, the artist’s work reflected the effects of acid rain, which was created when coal was burned; the sulphur and nitrogen byproducts drifted north into Canada, killing delicate black spruce trees. “No one, really, in the ’80s when I was showing this work, wanted to participate in the conversation,” Scott says. “People wanted to have happier moments in the landscape.”

Such romanticization can be traced back to late 19th-century Hudson River School painters, such as Thomas Cole, Thomas Moran, and Albert Bierstadt. These artists gave viewers beauty across large-scale canvases, sharing the ideas of Manifest Destiny and helping spur westward migrations to claim a piece of the American landscape.

These portrayals also instilled a mythology of the West that offered a utopia of fertile land to settle. Yet, it was Cole who gave the natural world a voice in The Course of Empire, a series of five paintings depicting a society rising from the wilderness, its ultimate collapse, and its reclamation by Mother Nature — as Scott describes it, a casebook study for what’s occurring today.

“While many of Thomas Moran’s and Albert Bierstadt’s Western landscapes seem to portray a primeval, unchanging wilderness, Scott’s paintings show the constantly shifting, ambiguous state of nature,” writes Laura F. Fry, vice president for curatorial affairs and collections at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Ghost Owls Mt. Rainier | Oil on Linen | 58 x 84 inches

Fry’s essay, “Michael Scott and Painters of the Nineteenth-Century American Landscape,” appears in the catalogue documenting Scott’s 2022 exhibition at the Cincinnati Museum Center, America’s Epic Treasures featuring Preternatural by Michael Scott. It showcased more than 30 of Scott’s paintings alongside historical landscape paintings and geological specimens. The exhibition encompassed four decades of Scott’s meditations on the natural world, including the aftermath of fire and the life-and-death cycle of scorched earth.

“By portraying constantly shifting environments, Scott invites viewers to consider humanity’s responsibility for our rapidly changing climate,” explains Fry, who was working as the senior curator of art at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, during the exhibition. “On viewing Scott’s paintings, one wonders how America’s lands will continue to change in the face of hotter fires, colder winters, and higher floods. With his contemporary homage to famous landscapes in the United States, Scott explores the surreal power and fragile beauty of the land and encourages respect for the unknowable, elemental forces of nature.”

Olympia Full Moon Summer Solstice | Oil on Canvas | 90 x 58 inches

The artist’s work stands as a beacon of imagination and beauty among the realities of global climate change. New vocabulary words like “megafire” seem just as surreal as his paintings, yet they describe the world in which we live.

“I wrestle with these ideas as I get older,” Scott says. “You don’t want to sugarcoat stuff, and so it’s a dilemma. You wish it weren’t this, but there have always been dilemmas in art. Great narrative artists are all about theater and the dilemma that’s in front of you.”

Scott invites the viewer into these worlds marred by disaster, which he composes and recomposes into a place of discomfort — paintings that “aren’t made for the sofa.”

“In some ways, it is a self-portrait of our own demise, using the animal as a metaphor,” says Scott. “Ninety percent of the animals that walked on the planet are now extinct. That’s a very hard conversation to be in.”

Yet, he finds beauty in these betrayals. “That is my goal as an artist: to make a beautiful painting,” he says. “It’s out of that seduction that you find out this is not necessarily an easy, idyllic, utopian place. This is under stress, and it is difficult to look at.”

No Comments