10 Mar The Spirit of Old Taos

IF JERRY JORDAN WAS A BETTING MAN — which he’s not, having grown up in a West Texas Pentecostal churchgoing family — he would never have put down money on the chances of ending up with the life he has. What are the odds of a 16-year-old farm boy wandering through the open door of a painter’s studio — which happened to be next to the park where the boy’s family was picnicking — and then having the artist finally agree to give the teenager painting lessons after a full year of persistent letters of request?

What are the odds of the boy’s father spending $4,000 in 1962 to build a studio for his son in a pasture on the family farm? Or of the family loading up the car and driving from Brownfield, Texas, to Taos, New Mexico, just so Jordan could see real art? This, after his father, who was having coffee in a Brownfield diner one day, announced that his 19-year-old son “wants to paint pictures for a living,” and a schoolteacher at the table replied, “Clarence, you need to take the boy to Taos. That’s where the artists are.”

“How I got here is just a miracle,” Jordan marvels, reflecting on the journey that led to becoming a widely collected artist working and living in what he considers, hands-down, the best place on earth.

To Jordan, that place is Taos, with the visually iconic pueblo and nearby aspen- and fir-covered mountains. It’s also the 2 acres of paradise just south of town where the 73-year-old painter lives with his wife, Marilyn. Cottonwood and fruit trees surround their 200-year-old adobe home, while an irrigation stream flows close by. In his separate studio, part of which is as old as the house, Jordan happily makes daily excursions into a timeless world reminiscent of his first and lifelong heroes in art.

Those are the early 20th-century painters known as the Taos Society of Artists, whose work Jordan first experienced during that pivotal visit to Taos as a teen. The family happened to stay at the Kachina Lodge, with walls adorned with paintings of the area and its residents by renowned Taos Society members, including Joseph H. Sharp [1859–1953], E. Irving Couse [1866–1936], Victor Higgins [1884–1949], Oscar Berninghaus [1874–1952], Bert. G. Phillips [1868–1956] and E.L. Blumenschein [1874–1960].

Jordan stood mesmerized in front of these paintings, and when he walked outside and rode through Taos in his father’s car, everything he experienced seemed imbued with the color and captivating quality of the art he’d just seen. “Now, this is the way I want to paint,” he told himself.

A few years later, Jordan and Marilyn moved to Taos for the first time, and he got busy painting. While his style was inspired by the Taos Masters, his choice of imagery at the time was influenced by his first mentor, the Texas painter whose studio he’d wandered into. That is, he painted a little of everything the market might want — Texas bluebonnets, still lifes, seascapes, horses, landscapes, hunting dogs with quail. In 1969, he showed 16 paintings to a curator in Lubbock, Texas, whose critique was devastating but honest: “You just paint all over the place! Find one thing and settle on it.”

Rather than finding one subject, Jordan gave up painting altogether for almost 10 years. He sold his house and studio, including all of his paintings, furniture and even the curtains. He and Marilyn moved to Tennessee, where he planned to work in real estate. But instead, Jerry, his brother, and their wives became The Jordans, a gospel/soft-country musical group with a side act in comedic storytelling, featuring Jerry’s authentic homegrown humor and West Texas drawl. They played the Grand Ole Opry and Madison Square Garden, and their best-selling album, “Phone Call From God,” sold a quarter-million copies in its first four weeks. In 1976, the album earned Jordan Billboard magazine’s Country Music Comic of the Year Award.

But something else was calling him. He remembers signing records in Nashville alongside country stars Marty Robbins and Jeanne Pruett one day, when Pruett asked what he thought about “all these people lined up for your autograph.” Jordan, who’d been painting a little on the side again, replied, “Well, if it was an art show, I’d be happier.”

In 1978, when MCA Records declined to renew The Jordans’ contract, he knew the time had come to do what he was most passionate about. He and Marilyn soon returned to Taos, and Jordon studied with acclaimed Taos painters Rod Goebel [1946–1993] and Ray Vinella [b. 1933], and New England artist William Henry Earle [1928–1992]. As he sank gratefully back into the place he loved so much, he found his “one thing” to paint: Taos — the pueblo, its people and the surrounding landscape.

Today, Jordan’s work is in the Taos Art Museum, which also owns the collection of the Taos Society paintings that once hung in the Kachina Lodge. Like that of the artists he enormously admires, his vision of Taos clearly resonates with collectors.

Last September, Jordan took part in the 2016 Quest for the West Art Show and Sale at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis, Indiana. “Jordan’s use of color, compositional style and subject matter — New Mexican people and places — had an immediate impact on patrons,” says James Nottage, the Eiteljorg’s vice president, chief curatorial officer and Gund curator of Western art. “Selling out in his first appearance at Quest, he is certain to be a favorite at future shows.”

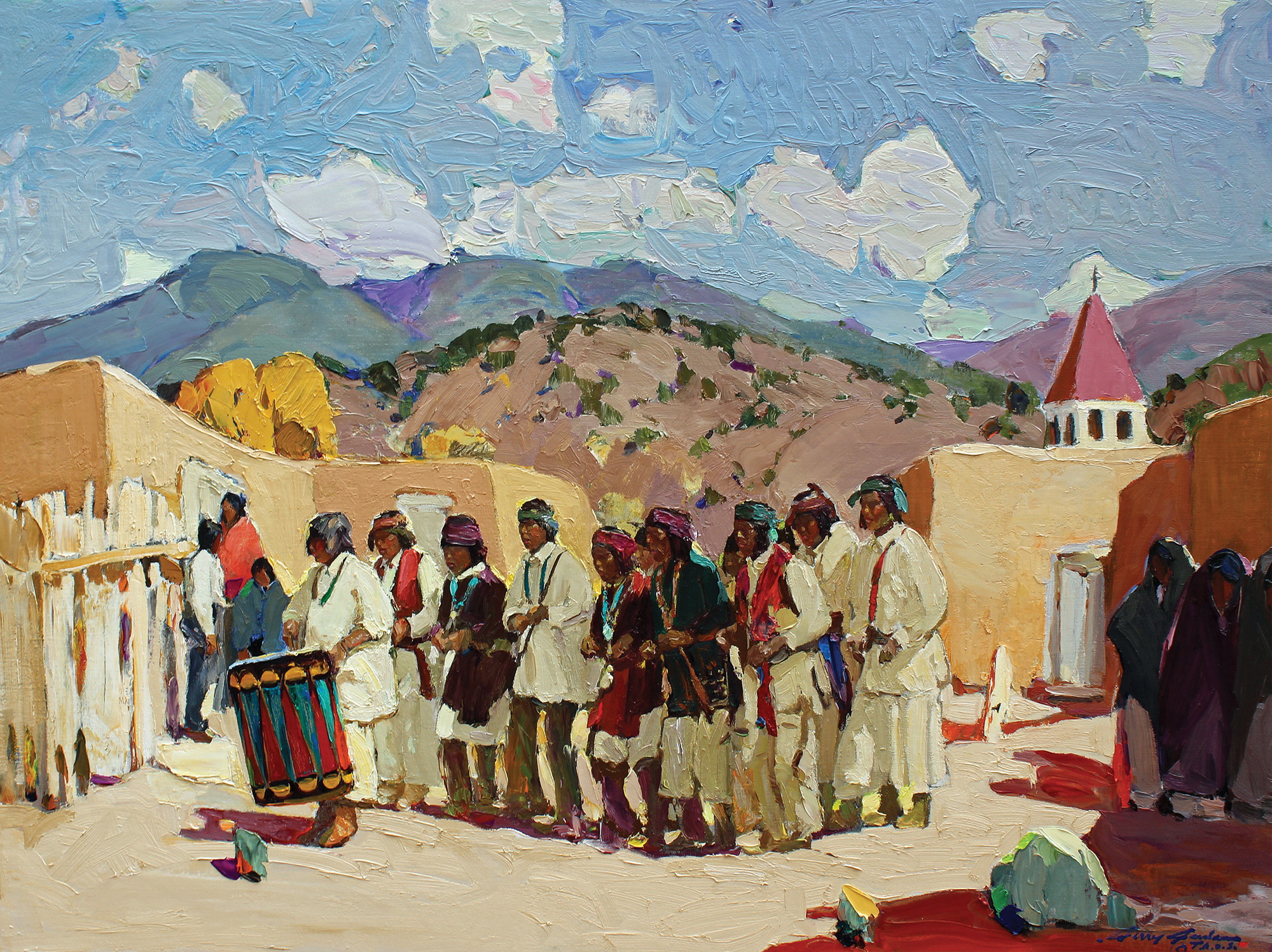

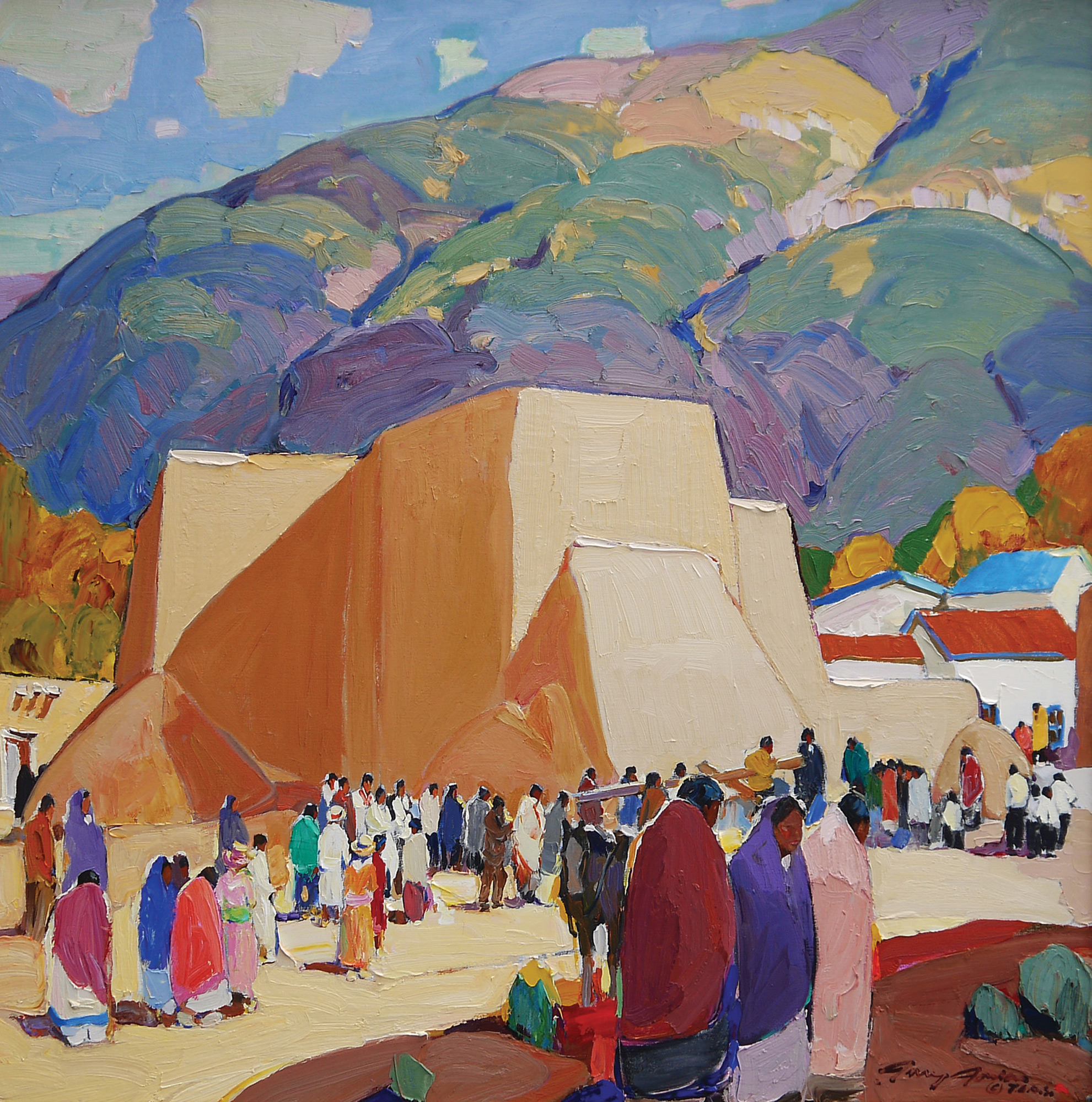

Although he long ago settled on the subject that most interests and stimulates him, Jordan has never settled for being good enough. “I strive with each painting to make it better,” he says. He continues to study original works by Blumenschein, Higgins and the other Taos masters, and spends days photographing longtime Native American friends. “They’re not that different from a hundred years ago,” he says of his models in their ancient pueblo setting. “Colorful blankets against the neutral colors of the pueblo — I can’t think of anything better.”

Recently, he’s been exploring what he sees as a slightly more Modernist approach to his signature, thickly textured, richly hued style. Shapes are more abstracted, with expressive brushstrokes and color rather than detail informing the eye. “The brushstrokes seem quick, but they’re well thought out,” he says of this work.

Jamie McLaren, art consultant at Manitou Galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico, agrees. “Jerry’s attention to composition is thoughtfully comprehensive and undertaken with great intent,” McLaren says, noting that the result steers the viewer’s eye in and around his works in a wonderfully intended manner. “His movement of paint, with brush or palette knife, also contributes to his deliberate directional dynamic. On a personal note, Jerry — I call him the ‘Maestro’ — has a generous heart and is among the most appreciative souls I’ve had the pleasure of representing, and calling my friend, for almost seven years,” McLaren adds.

Regardless of how his work may develop, Jordan remains steadfastly dedicated to the spirit and vision of the early Taos artists and the landscape and cultural richness that excited them. “I’m still more inspired and intrigued by these artists than any others,” he says. “I’m always asking myself: How did these guys think? It’s been a lifelong study of mine, and here I get to live in Taos — it’s pretty cool.”

Gratitude for his life’s improbable turn of events is reflected in the four letters Jordan has added under his signature on every painting since 1985: T.A.O.S. It’s his special code for “Together Always Our Spirit.”

- “Generational Threads” (detail) | Oil on Canvas | 58 x 58 inches

- “When the Last Leaf Falls” (detail) | Oil | 11 x 14 inches Courtesy of Manitou Galleries

- “Times of Refreshing” | Oil | 36 x 36 inches Courtesy of Manitou Galleries

- “Insistent Seasons” | Oil | 16 x 20 inches | Courtesy of Parsons Fine Art

No Comments