09 Jun Alla Prima

IN THE SUMMER OF 2011, Ewoud de Groot and his friend, the piscatorial painter Jeb Todd, were fly fishing Montana’s Shields River, a sweet meander of cobbled troutwater flowing off the southwestern corner of the Crazy Mountains.

“We were in the countryside, with our waders on, and there, perched before us in the middle of nowhere, was Batman,” the Dutch nature artist and sportsman says in his thick accent, still effusing genuine amazement in his voice.

Casting a line next to them wasn’t literally the caped crusader, of course; it was Michael Keaton who played the comic book action hero twice in Hollywood films. Memorable about the encounter for Todd wasn’t that the pair ran into Keaton, a serious angler who owns property nearby. It is that the actor had no inkling who de Groot was — though perhaps this year it could change.

Praised internationally as a rising star in wildlife art, Ewoud (pronounced AY-VUDE) de Groot is embarking upon the most important barnstorm of his career. His work will be appearing this year in a succession of major gallery events across the American West. The schedule is exhausting just to think about: A one-man show opens in early June at Visions West Gallery in Bozeman, Montana. It will be followed by another marquee event at Gerald Peters/Santa Fe later in June, then a two-man collaboration featuring de Groot and Mark Eberhard at Astoria Fine Art in Jackson, Wyoming, in July. In September, de Groot will have a couple of pieces at the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s Western Visions Exhibition in Jackson Hole. Finally, come November, he’ll be artist in residence at the Rockport Center for the Arts in Rockport, Texas.

On the strength of intensive field research in the U.S. and Europe, de Groot has been forcibly sequestered in his studio at Egmond aan Zee, Holland, creating 100 new works. Nikki Todd, owner of Visions West Galleries, notes that anticipation for the Bozeman show has been building among collectors. Few contemporary European nature painters, absent, say, Belgium’s Carl Brenders and Sweden’s Lars Jonsson, have managed to crack the discriminating American market. Then again, having worked for a time on a fishing boat in Alaska and making at least one pilgrimage a year to the Rockies, de Groot knows and loves the avifauna of this continent.

“I consider myself a wildlife artist, but my identity is not as an artist who paints only a representation of wildlife. I want to convey a mood through color, offer an ambiance that can fill up a room like sunshine coming in through the window,” he says.

“Ewoud is a first-rate painter,” Nikki Todd says. “He’s a master of mechanics, gesture and movement, yet his unconventional execution lends a lyric and pared-down style that sets his work apart from a lot of wildlife painters out there today. He is a genius at capturing light in his abstracted backgrounds. They have a pulsating, magnetic shimmer to them.”

As a painter, de Groot’s force is achieved through visual imbalance, combining mesmerizing color bands à la Mark Rothko and negative space as counterpoints to his subjects. Oftentimes, his most distinctive focal points — birds of prey — are flying headlong toward the viewer. For those who may have calmer sensibilities, de Groot’s affinity for water avians — sandhill cranes, loons, phalaropes and egrets, among them — are nothing short of soothing visual meditations.

In Hawk Owl, 27.5 by 55 inches, as with de Groot’s series of snowy and great grey owls, he flies a raptor, mid air, straight ahead off the canvas. In Sandhill Crane 2, de Groot sets the elegant body language of the wading bird against three tiers of background color. With the work, Loons, massive at 47 by 47 inches, patchwork vertical patterns are intermeshed with wispy horizontal lines.

Seldom, if ever, does de Groot stand accused of overrendering, the curse of artists who mistake profusion of detail with more refined composition and design. Oozing with a spontaneous energy, his scenes, sometimes measuring 4 feet wide, are whirs of color that seem to have emerged through a prism of random abstracted shapes.

Born in 1969, de Groot says he was influenced (“how could I not be?” he asks) by exposure to the usual list of great Dutch and Flemish painters going back more than half a millennium. But as a teenager who was fanatical about birding, filling sketchbooks with literal interpretations of subjects, he says that the late magical realist Rien Poortvliet [1932 – 1995] had a huge effect. As an ad man turned book illustrator, Poortvliet’s finished drawings and paintings of wildlife — as well as his surreal works completed for a series of best-selling books on, of all things, gnomes — were, for a young de Groot, embraced as refreshing alternatives to photo-realism and non-representation.

“The high-brow art establishment in Holland, of course, looked upon Poortvliet’s commercial work, especially his portrayals of gnomes and animals, as being kitsch, but he could draw and was in fact a hell of a painter able to work in a variety of media. More than anything,” de Groot says, “he showed me how originality comes from experimentation. ‘It’s important to be authentic to yourself’, he said, ‘not to worry about appeasing other people.’”

On a palette board, de Groot’s arsenal of oils looks like an oozing volcanic eruption telegraphing a fondness for painting alla prima. He may have 10 to 15 different paintings going at one time, an approach that leads not to distraction, he says, but synergy. Each work pushes de Groot to strive for maximum impact.

“It fires my creative process rather than stunts it. My technique is based on the principle of painting in layers, using, typically, cold bluish grays and warm brownish grays,” he says. “I start a painting by sketching with big brushstrokes and using the palette knife to look for the right composition, not allowing myself to be distracted by specifics. Once the form of the painting has been established, then I begin to work on the birds or a particular detail of the subjects themselves.”

Maria Hajic, senior curator at Gerald Peters/Santa Fe will never forget her inaugural exposure to de Groot’s work after he was juried into the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum’s annual Birds in Art Exhibition in 2002. “My first impression was similar to what I felt when I first viewed Ron Kingswood’s earlier animal paintings. ‘Wow, this is so refreshingly different,’” Hajic explains. “Both these artists take apart the natural world and reassemble it in unique ways. Ewoud uses light, bold color and expressive brushwork to capture our attention. You rarely see a horizon line in his paintings; the viewer is drawn in to the composition creating a more intimate encounter.”

Hajic says de Groot’s work marks a clear departure from traditional Realism, and is as much about stylistic and compositional experimentation as about the animals he portrays. Consequently, she notes, his artwork has broad appeal — from interior designers looking for signature pieces in distinctive homes to collectors of wildlife art captivated by his contemporary flair. Hajic notes that in winter 2012 de Groot won over a new genre of collectors — high-end sporting-art mavens attending the Safari Club International gathering in Las Vegas. Peters is showcasing de Groot in a group exhibition titled Reflective Nature that opens on June 22, 2012, and includes Susan Brearey, Burt Brent and Les Perhacs.

Among de Groot’s devoted collectors are New York attorney Donald O’Brien; Bill and Joffa Kerr, founders of the National Museum of Wildlife Art; and actor Kelsey Grammer. Simon Gudgeon, the renowned British sculptor who is having his iconic work, Isis, installed at the National Museum of Wildlife Art this summer, says de Groot brings a vision that marries European-style naturalistic interpretation with a modern North American flourish.

In 2005, Gudgeon was attending Birds in Art at the Woodson Museum and stood rapt before de Groot’s stunning piece, Oystercatchers. “It captivated me, so much so, that I bought it,” Gudgeon says, noting that it now hangs among several de Groots in his personal collection. “His are true works of art that transcend the boundaries between wildlife and contemporary art. They have a vitality and immediacy. They never tire because there is always some new element to explore.”

While de Groot’s choice of subjects has verged into iconic mammals, his forte remains birds. Indeed, he has so many new ideas churning for bird paintings that he finds it difficult to sleep.

“I can’t wait to get back to the West — to get outside and just wander. But before I arrive in America, I’m going to be painting until the last possible moment. Are my painting surfaces ever dry when I ship them? Never! When they hit the gallery walls in Bozeman, Santa Fe and Jackson Hole, I’ll barely be wiping the oil from my brushes and fingertips. Then I’m reaching for the fly rod.”

- “Hawk Owl” | Oil on Linen | 27.5 x 55 cm | 2010

- “Restin Oystercatchers” | Oil on Linen | 100 x 100 cm | 2005

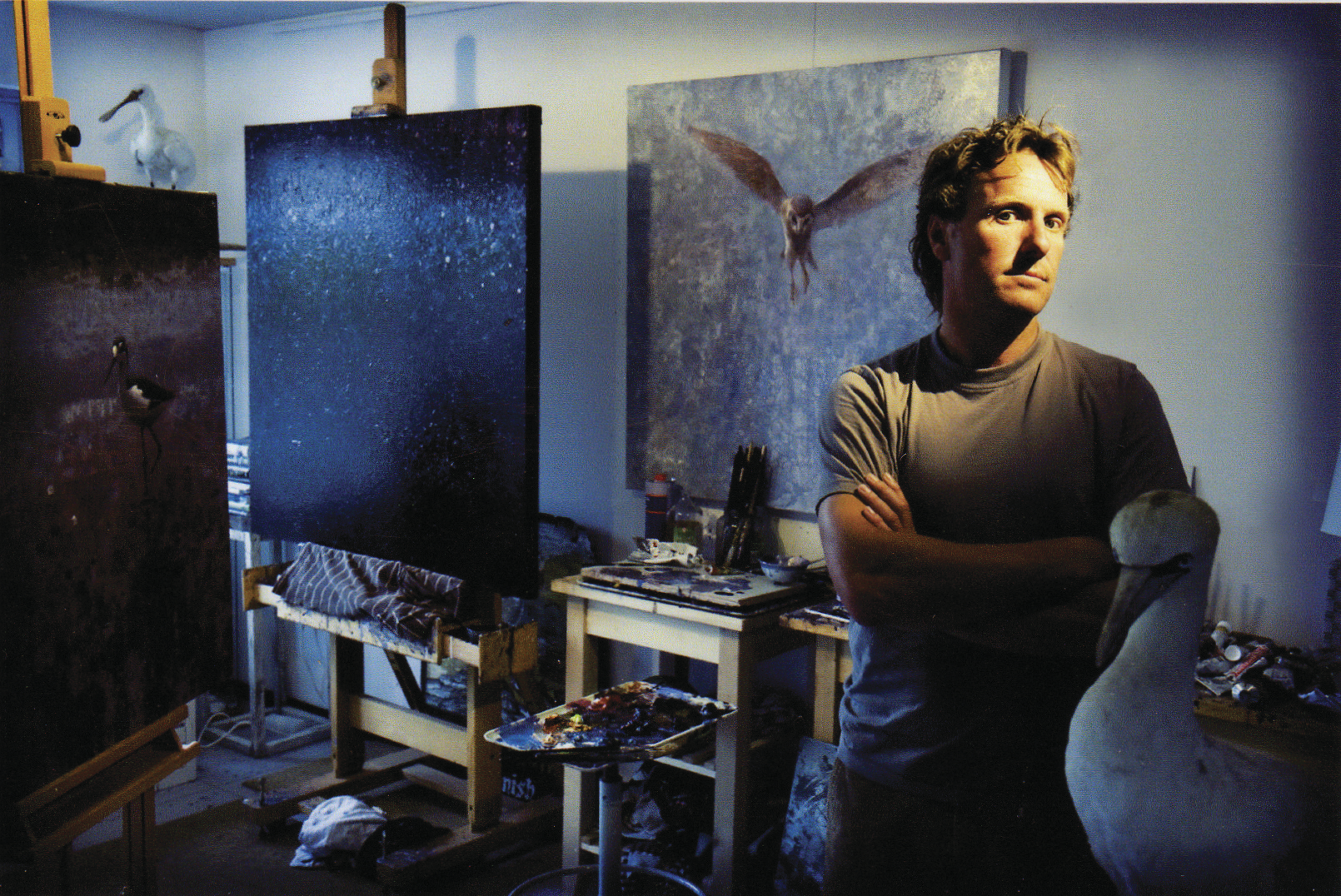

- Painter Ewoud de Groot in his studio

- Ewoud de Groot’s palette

- “Winter Swan” | Oil on Linen | 110 x 110 cm | 2010

No Comments