11 Mar Rendering: Bauhaus: Reflecting on 100 Years of Influence

It was a small German art school that lasted a mere 14 years from 1919 to 1933, suffered squabbles regarding its core philosophy and teaching methods, was forced to move from Weimar to Dessau to Berlin, and had three radically different directors. It certainly didn’t invent Modernism, and many of the ideas it espoused were already in the air, but 100 years after its founding, the Staatliches Bauhaus remains one of the most profound influences on modern architecture and design.

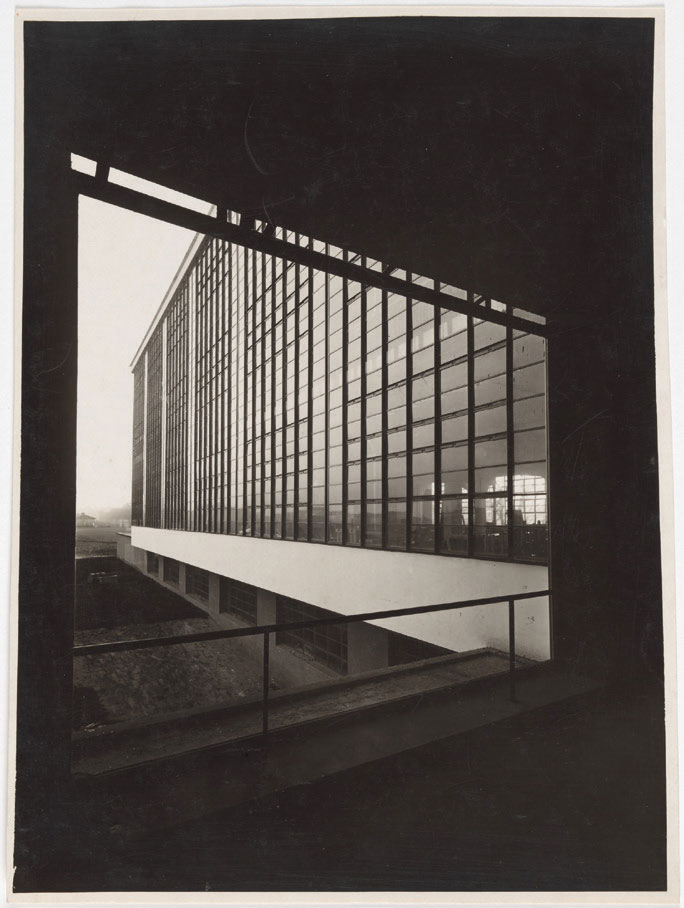

Gelatin Silver Print | Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, BRGA.20.24. ©Lucia Moholy Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo: Harvard Art Museums; ©President and Fellows of Harvard College.

So what was the Bauhaus? Its name translates to “building house” or “construction house,” but it began as an avant-garde school that sought to erase the elitist line between craftsmanship and art via workshops. But even that idea existed. What made the Bauhaus historic was its gathering of gifted faculty striving toward breakthroughs in style, including Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, Wassily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, and former-students-turned-instructors, Josef Albers and Marcel Breuer. Coupled with gifted students, the school’s driving energy was to create free of influences from the past, in an atmosphere in which art and technology were no longer opposing forces.

Haus am Horn in Weimar, Germany, designed by Georg Muche. | Courtesy of Freundeskreis der Bauhaus- Universität Weimar e. V.. Photograph ©Cameron Blaylock

The founding director, Walter Gropius, worked as a young architect for Peter Behrens from 1908 to 1910. Behrens was considered Germany’s most innovative architect, a founder of the Deutscher Werkbund, an organization which advocated for the idea that industrialization and mass production, rather than the enemy of art, could be wed to creativity. In the age of IKEA, this idea might seem ho-hum, but in the early 20th century, it was revolutionary.

A photo by Lucia Moholy of the Masters Housing at Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany. This was Moholy and László Moholy-Nagy’s living room (1927–28). | Gelatin Silver Print with Opaque Watercolor Retouching | Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, BRGA.21.55.A. ©Lucia Moholy Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo: Harvard Art Museums.

During his tenure with Behrens, Gropius worked alongside Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and, for some months, Le Corbusier. It’s tempting to imagine the ideas they might have shared.

After Gropius left Behrens’ office in 1910, he partnered with architect Adolf Meyer to design two landmark Modernist factory buildings. One of these, the Fagus Factory, was marked by an absence of ornamentation and a steel frame that replaced support walls and allowed for large expanses of glass. This first commission allowed Gropius to apply his revolutionary ideas in three dimensions.

It’s been said that in later years Gropius hijacked the mythology of the Bauhaus and made it his own, despite the many disparate voices and approaches that were a strong part of the school’s evolution. But he was the longest director, and its most dedicated cheerleader.

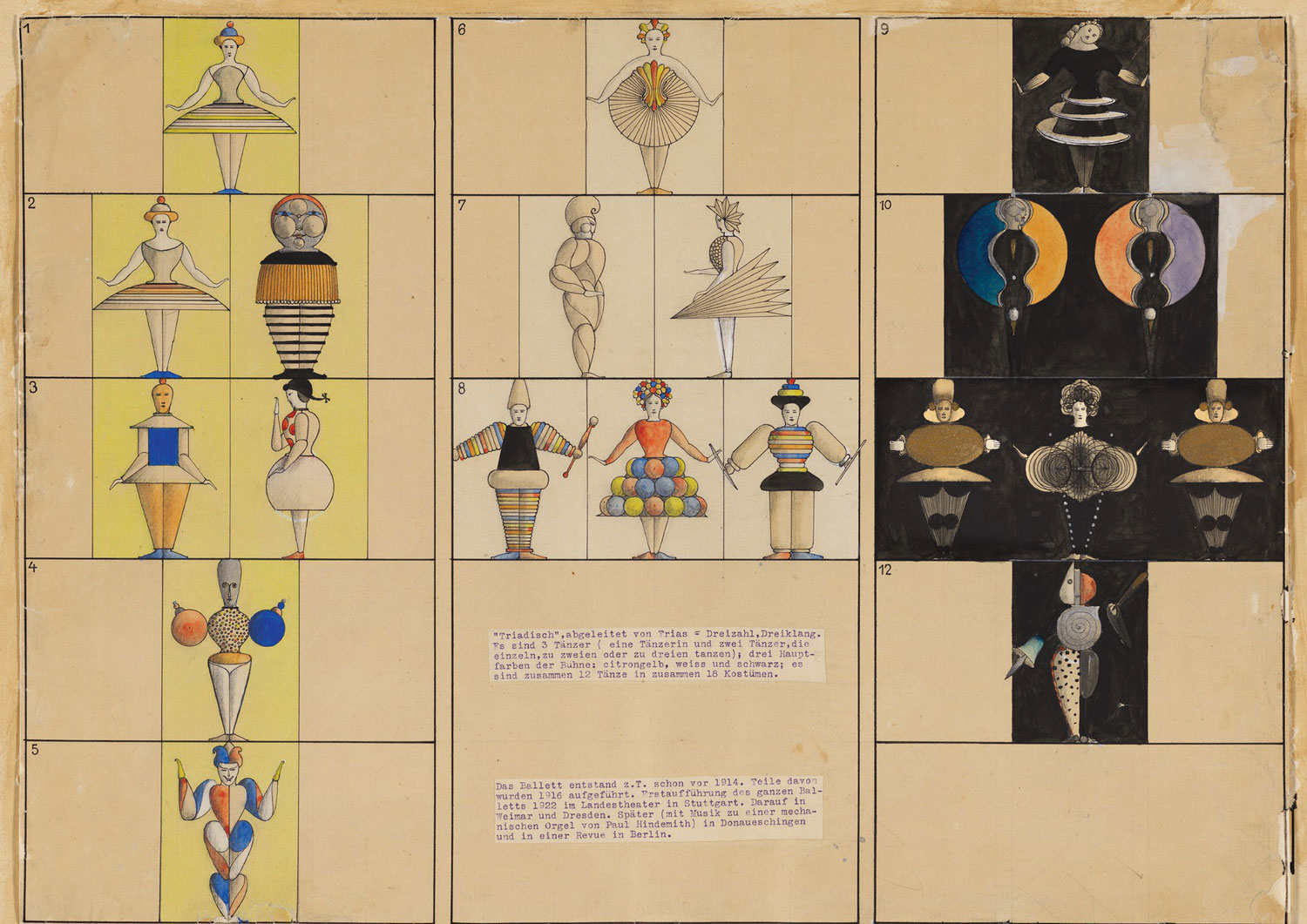

Costume designs for “Triadic Ballet” by Oskar Schlemmer (1926). | Black Ink, Opaque Watercolor, Metallic Powder, Graphite, and Typewritten Collage Elements on Cream Wove Paper Mounted to Cream Card | Harvard Art Museums/ Busch-Reisinger Museum, BR50.428. Photo: Harvard Art Museums.

In the beginning, students were required to finish a six-month introductory program, after which the brightest took part in apprentice-style workshops (rather than academic classes) teaching design, form, and color. Each was co-taught by a craftsman and an artist known as Masters of Craft and Masters of Form. Metalworking, carpentry, stained glass, photography, and typography, among others, were offered in workshops.

Design for a Rug by Anni Albers (1927) | Black Ink and Watercolor over Graphite with Cut and Drawn Paper Additions on Off-White Woven Paper | Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, BR48.49. ©The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Harvard Art Museums.

Tapestry by Gunta Stölzl (1922–23) | Cotton, Wool, and Linen Fibers | Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, BR49.669. ©Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo: Harvard Art Museums.

Pieces created by students and lecturers that continue to inspire awe in their inventiveness and beauty include the Wassily chair by Breuer, the tea set by Marianne Brandt, and the table lamp by Carl Jacob Jucker and Wilhelm Wagenfeld. The idea was to create mass-producible products of simple beauty that could be personalized with small changes.

The German state of Thuringia, which financed the school, had quickly gone from a liberal government to conservative and disapproving; in 1925, the school was closed. It reopened in Dessau, where the city government was more welcoming.

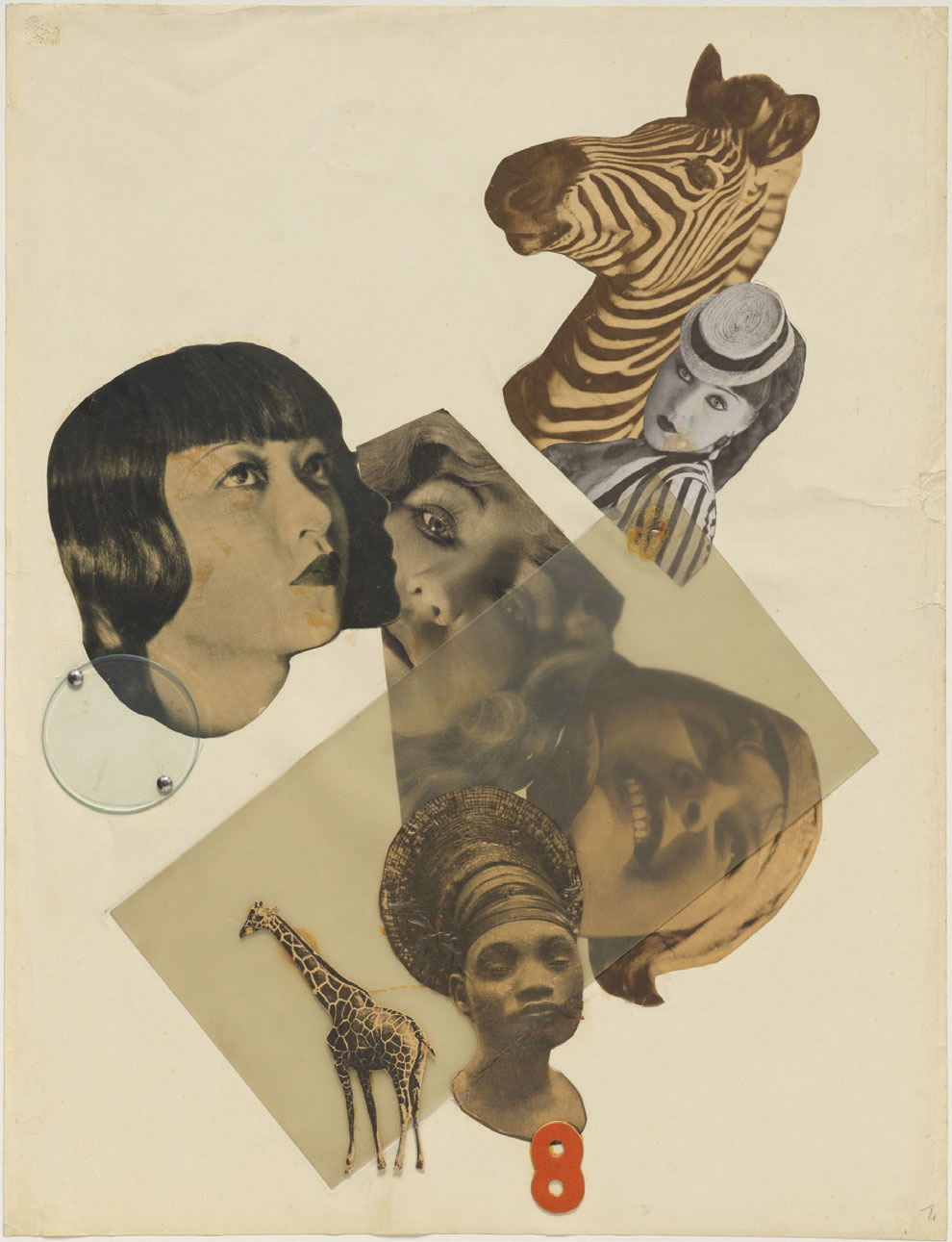

Untitled (with Anna May Wong) by Marianne Brandt (1929) | Collage of Cut and Printed Papers, Cellulose Acetate, Glass, Metal Rivets, and Flocked Paper on Paper Board | Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, 2006.25. ©Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Harvard Art Museums.

Gropius designed the school’s three-pronged new building, which garnered much attention. Designs for the new masters’ houses employed classically Modernist flat roofs over basic cube elements. Ideally, the cubes could be added onto or rearranged to create individuality among the economical, uniform elements.

Verdure by Herbert Bayer (1950) | Oil on Canvas | Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, 1950.169. ©Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo: Harvard Art Museums.

Until 1927, there was no official architecture department at the school. But all along, students, and in fact, most of the workshops, had worked on private commissions taken on by Gropius and Meyer. So technically there are few actual Bauhaus buildings — they’re more accurately described as Bauhaus style. The ideal was for all of the crafts to come together and create a complete work.

A Bauhaus-inspired building designed by Yehuda Megidovitz. Courtesy of Bauhaus Center Tel Aviv.

Life at the Bauhaus wasn’t all seriousness. There were frequent costume balls where the students outdid one another with elaborately constructed, playful clothing designs. Look at photographs of the students and the energy and enthusiasm is evident. But at the same time, the Nazis were rising to power and judged the Bauhaus as “degenerate art.” Hannes Meyer, the director from 1928 to 1930 (chosen by Gropius) was fired by the Dessau mayor for his Communist leanings, but in fact, Meyer repudiated much of the Bauhaus philosophy and had already forced out many masters. The final director, Mies, oversaw the school until Nazis took over the Dessau city government and cut off funding in 1932. Mies briefly secured private funding and reopened the Bauhaus in Berlin, but it was closed by the Nazis in 1933.

A view of the backside of the Fagus factory. Courtesy of UNESCO-welterbe Fagus- werk.

What the Nazis couldn’t have anticipated was that fleeing students and professors would spread the school’s influence across the world. A number went to Palestine, where they created the White City, some 4,000 Bauhaus-influenced buildings in Tel Aviv, Israel, now a UNESCO world heritage site. Many key figures (which reads like a “who’s who” of early Modern art and architecture) moved to the United States. Gropius was the chair of Harvard’s Department of Architecture from 1938 until he retired in 1952. Mies left Germany in 1937 and became head of the architecture department at what would become the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he also designed much of the campus. Breuer followed Gropius to Harvard and left to form his own New York architectural practice in 1941. Moholy-Nagy ran the New Bauhaus in Chicago, Illinois, which lasted only a year. He then founded the Institute of Design, which was absorbed into the Illinois Institute of Technology. Albers became an art professor at the fabled Black Mountain, then joined the design department at Yale. These Bauhaus veterans had a profound effect on American architecture, art, and design. The influence of the Bauhaus reaches far beyond a school of thought, shaping concepts of art and design around the globe today.

No Comments