30 Apr “Just an artist”

There have been moments in artist Francis Livingston’s life where something suddenly shifted inside him, with consequences lasting throughout his career. One such moment occurred while he was a young illustration student at San Francisco’s Academy of Art College in the late 1970s. During his final year of school, Livingston was among several students who worked for publishers that paid entry-level wages to unseasoned illustrators. Although he pushed himself to the extreme at the academy, he was putting out what he calls “okay stuff” for the publisher.

Leaf Dream | Oil | 12 x 12 inches

One day, a friend and fellow student, producing beautiful illustrations for the same company, approached him. “‘Francis, you haven’t suffered enough,’” Livingston recalls, in his quiet, low-key manner, his friend’s words. The comment struck home. “I got it. I realized I had to get back to putting every bit of myself into every single thing I do, no matter how small.”

Another important moment took place at a comic book convention in New York City. Comic books had been one of Livingston’s passions since boyhood. He remembers going to the Rexall Drug Store in the small Oklahoma town where he’d grown up, excited to buy the latest installment of his favorites. He loved to draw and dreamed of becoming a comic book artist.

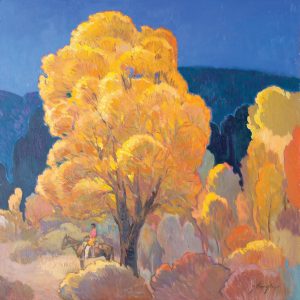

Golden Forest | Oil | 36 x 36 inches

At the convention, Livingston came across a room where one of his idols sat surrounded by magnificent book covers and other testaments to an award-winning illustration career. Although known for his fantasy and comic book work, the man told Livingston he was not a comic book artist or a fantasy artist. “I’m just an artist,” he said. Livingston remembers thinking, “Yeah! Why limit yourself? Why put yourself in a box?”

Another defining moment happened when Livingston was a high school student and visited the newly opened National Cowboy Hall of Fame (now the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum) in Oklahoma City for the first time. As he walked through the museum’s art collection, he stopped, stunned, in front of a large-scale painting by N.C. Wyeth. He was amazed to see thin paint in places and thicker paint depicting the effects of sunlight streaming through the Western scene.

Storm Gathering | Oil | 24 x 24 inches

Further along, he came across works by Frederic Remington and Nicolai Fechin. But Livingston was especially mesmerized by an Ernest Blumenschein painting. It was one of the famed Taos Society artist’s later, beautifully designed, almost abstract pieces. Something about the shapes and colors “just really stuck with me,” he says, speaking from his home south of Ketchum, Idaho, where he and his wife, artist Sue Rother, have lived and worked since the mid-1990s.

Livingston has never confined himself to a box throughout his long and highly acclaimed illustration and fine art career. His illustrations appear in magazines like The New Yorker, book covers, posters for musical and theatrical events, ads, annual reports, and numerous other applications — he drew and painted every kind of subject imaginable. He continually refined his skills in mediums from pen and ink to watercolors, acrylics, and oils, and in countless styles. Illustration was the perfect training ground, an endless opportunity to experiment and play in an era when everything was created by hand. And he never forgot his early commitment to putting all his effort and talent into every project.

Aspen Hills | Oil | 36 x 36 inches

As much as Livingston loved drawing as a boy, in high school, he faced a fork in the road: Should he pursue art or law? He was good at art, serving as a teacher’s assistant in the school’s art department and earning the title of “most artistic” in the school yearbook. But he also excelled at debate, drama, and speech. Perhaps due to encouragement and attention from an art teacher he especially respected, “who saw something in me,” Livingston says, he turned in that direction. Following graduation, he headed to Denver to attend the Rocky Mountain School of Art (now the Rocky Mountain College of Art + Design).

The two-year school was helpful for gaining fundamentals in art and illustration, but Denver at the time didn’t offer much in the way of employment in commercial art. So, in 1975, Livingston moved to San Francisco for intensive illustration training at the Academy of Art College. There, the instructors were active professional illustrators, some of whom were “people you just didn’t want to disappoint,” he says. Livingston soon realized he wasn’t cut out for the laborious sequential process required of comic book art. He was also exposed to and inspired by fine artists showing in San Francisco, including California Modernists Richard Diebenkorn and Wayne Thiebaud.

Leaves of Autumn | Oil | 36 x 36 inches

For Livingston, illustration work and fine art overlapped for a number of years. Unlike many former illustrators, he feels no need to downplay that portion of his career. Like his early idol, he considered himself simply an artist all along.

Then, in the late 1980s, he received a different kind of “assignment.” A fine art dealer who was opening a small gallery and had seen some of his paintings offered him a solo show. Eventually other galleries followed, and today Livingston’s work is exhibited around the country and collected internationally. Years after his first exposure to paintings by Taos Society artists, he found himself circling back to that initial spark and the inspiration he still feels from their art. Livingston’s body of work also includes urban scenes — especially featuring older, interesting architecture and vehicles — landscapes, still life, and pure abstraction.

For galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Tucson, Arizona, Livingston focuses primarily on Southwest scenes, often containing blanket-wrapped Native figures, as did the early Taos painters he admires. The artist will exhibit new works during a solo show, August 15 through 28, at Meyer Gallery in Santa Fe. Gallery owner John Manzari notes that what stands out most for him is how Livingston “draws from tradition, especially the inspiration from the Taos Society of Artists, while still making the subjects entirely his own.”

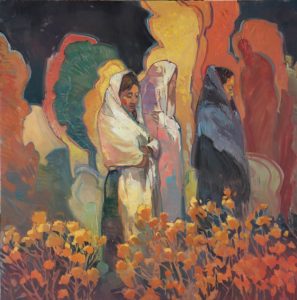

Forest Spirit | Oil on Panel | 36 x 36 inches

Verde Forest falls in this genre while also reminding Livingston of N.C. Wyeth’s use of the spotlight effect of sun hitting just one area, as often happens in nature. The painting features a lone man on horseback in a wooded summer scene, a departure from Livingston’s frequent use of warm, autumn-inspired hues. His art reflects an intuitive process of applying paint primarily as a balance of shapes, colors, and values rather than details, even when the subject remains naturalistic. “I don’t focus on it as a horse and trees. It’s all about spatial relationships and the shapes of things,” he says.

Verde Forest | Oil on Panel | 40 x 40 inches

Forest Spirit, whose three figures are echoed by colorful tree forms behind them, reaches further into a mixture of realism and abstraction. “There’s a sense of beauty with these people, and enough to focus on, but what I really enjoyed was the shapes of the trees,” the artist says. At other times, he fully embraces the compositional elements and creates works of pure abstraction. “But it’s all the same kind of thinking for me.”

Mark Sublette, owner of Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson, Arizona, has represented Livingston for many years. He describes the painter’s approach as “thick, juicy brushstrokes applied with a surgeon’s skill, set in a kaleidoscope of color.” For Livingston, it’s all part of a lifelong artistic exploration. As he puts it, “I like experimenting to see what happens, and I try to be fearless about it.”

No Comments