12 Jul A Quiet Resonance

THE JAPANESE TERM SHINRIN-YOKU, which translates to “forest bathing,” refers to the practice of connecting with and taking in nature to improve one’s mental and physical well-being. This idea is not new, of course, and has been studied by scientists across the globe who discovered that even small amounts of time spent outdoors can have quantifiable healing effects on one’s body and mind.

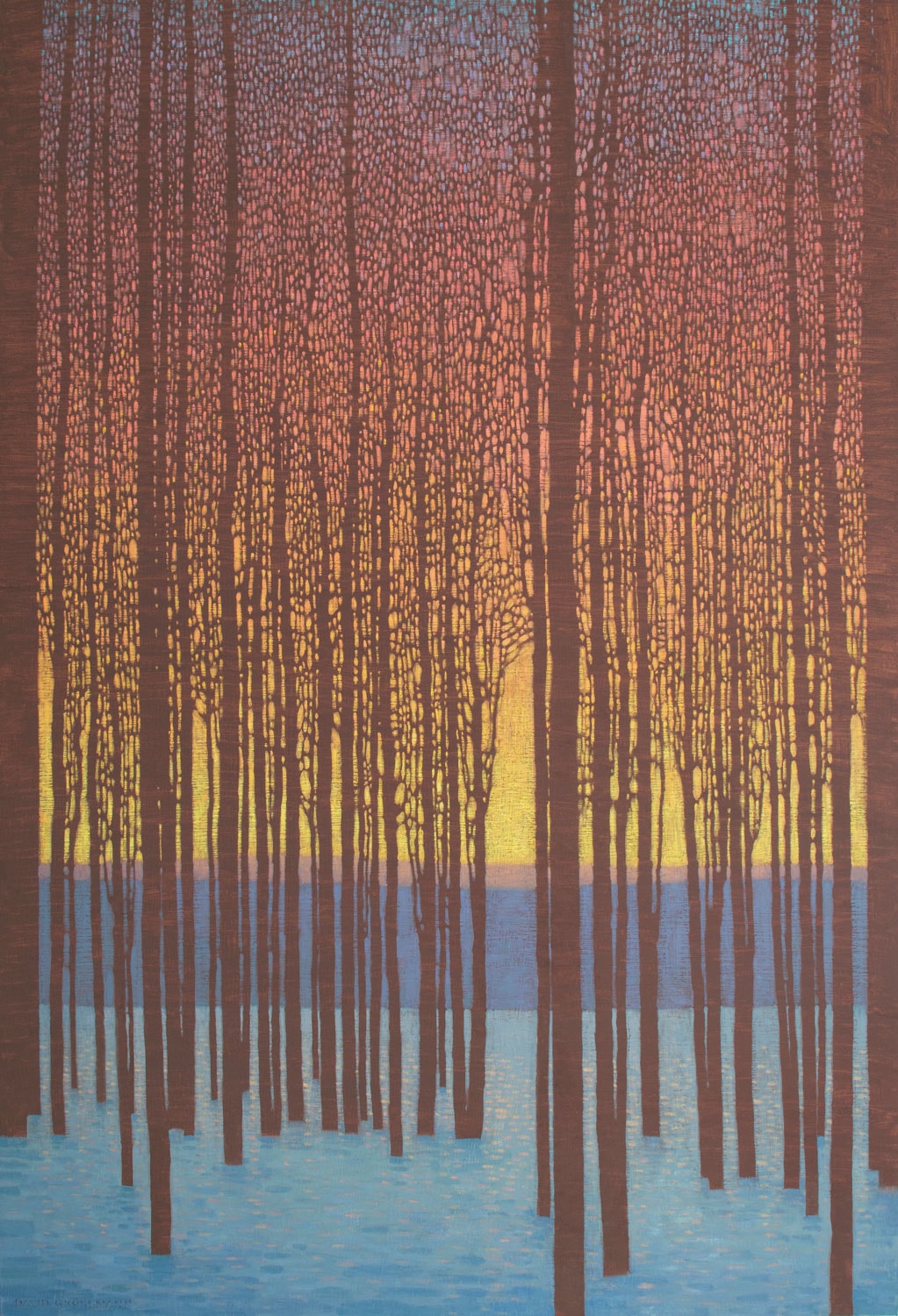

Stained Glass Sky | Oil on Linen Panel | 60 x 40 inches

Landscape painter David Grossmann might not say his work involves forest bathing, but, in so many ways, this is precisely what he’s doing. One could posit that time spent soaking in Grossmann’s delicate brushwork and snips of close-toned colors, hues that vibrate off each other to create paintings that drift between real and imaginary, more poem than prose, could indeed drop one’s blood pressure in the spirit of shinrin-yoku.

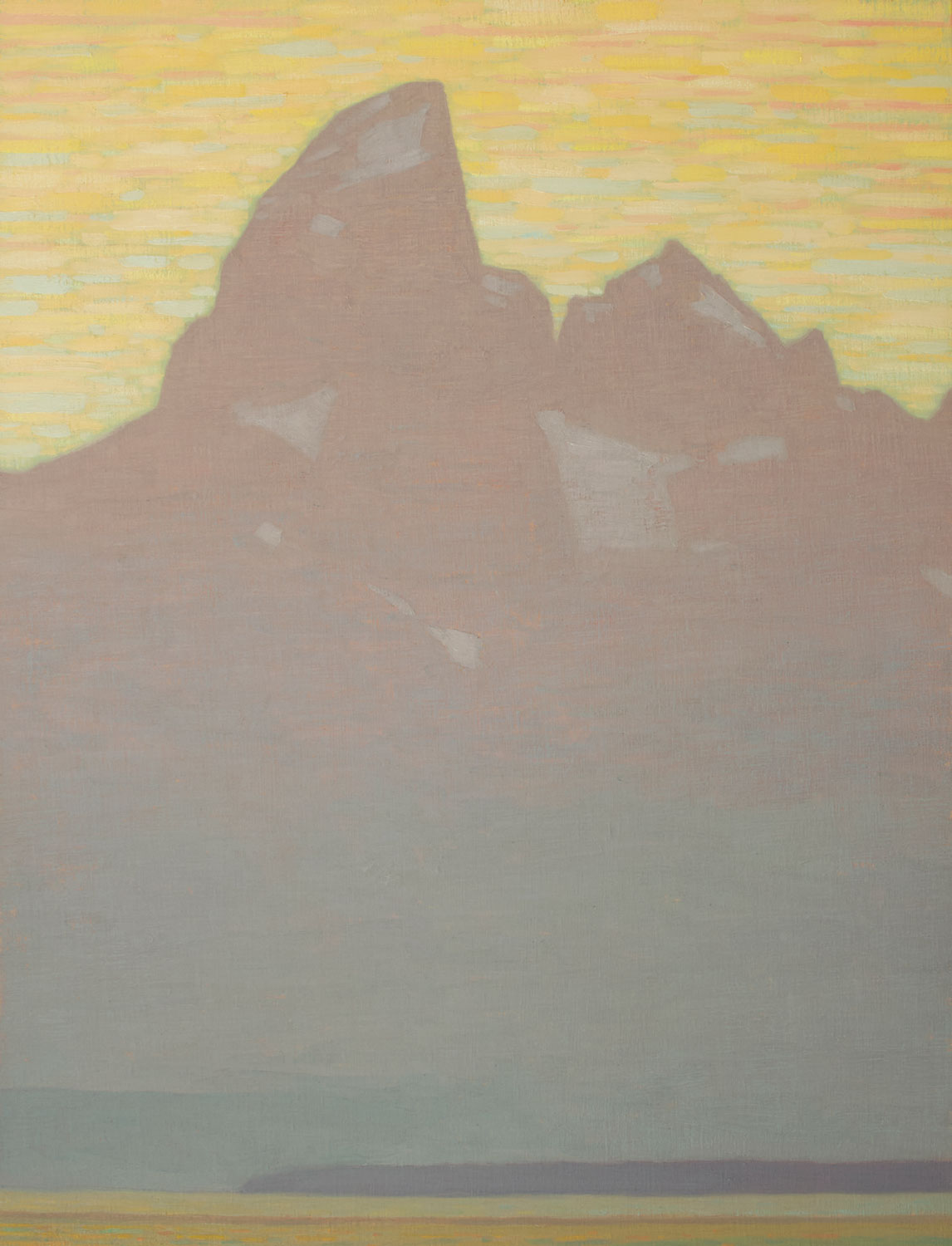

Because there is something about Grossmann’s paintings. They’re not detailed scenes or dramatic depictions of majestic mountains, roaring waves, or cloud formations. They’re quiet, and yet they won’t easily fade from your mind, like a Polaroid left in the sun. Grossmann’s work lingers, it calls to you. But why? That story started long before he ever picked up a brush.

The son of missionaries, Grossmann was born in Colorado but grew up in Chile surrounded by the beauty and isolation of an unfamiliar culture and language. “I always struggled to find where I fit in,” he says. “And I always struggled with words. I spent hours drawing and painting; art became a place of refuge, a way to express myself without words.”

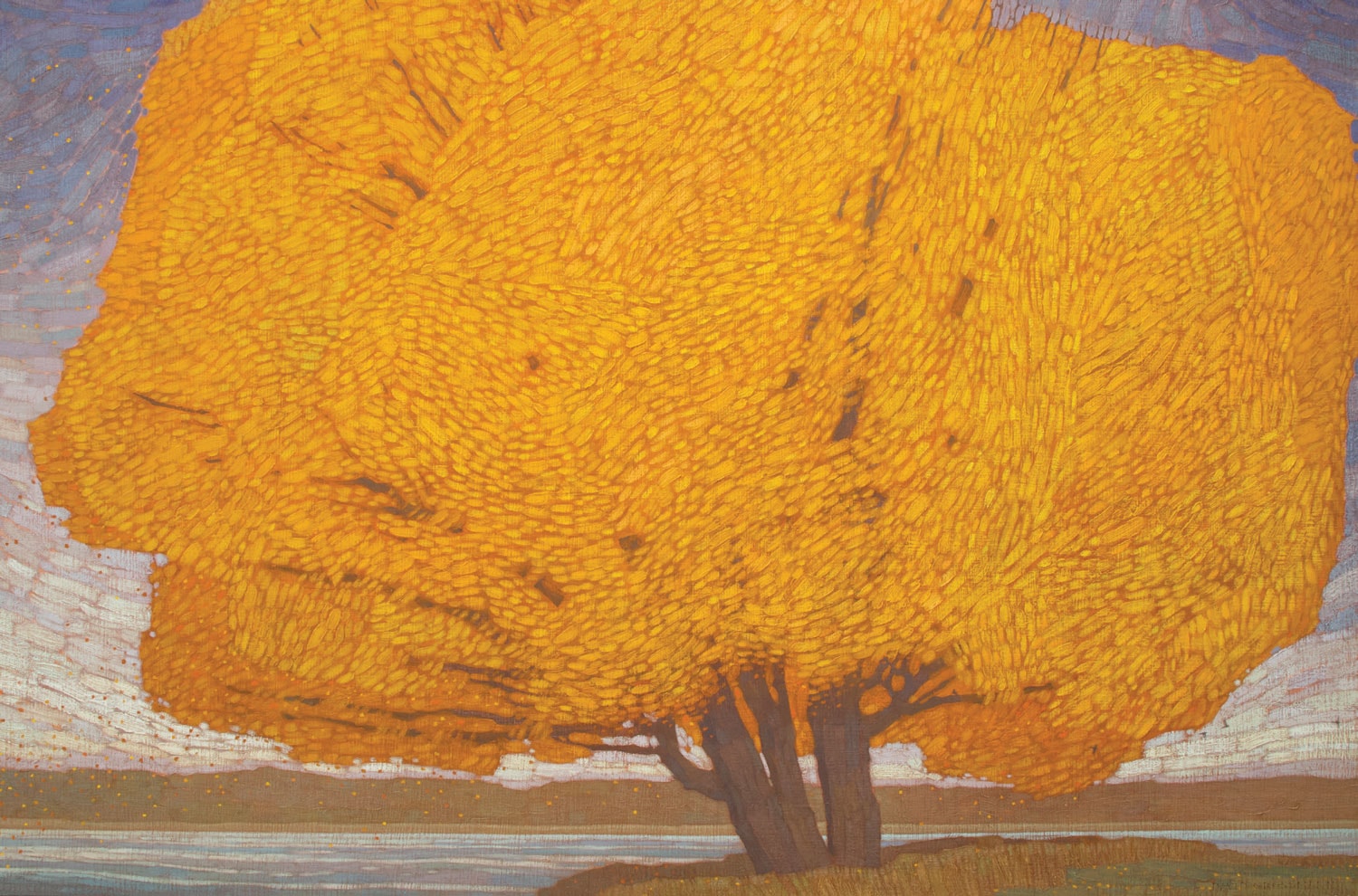

In Motion | Oil on Linen Panel | 40 x 60 inches

During the years that his family lived abroad, something else took hold: an understanding that the way we live can have a profound impact on others, whether we know it or not. “My parents tried to bring hope and beauty into other people’s lives,” he says, by way of describing his artistic intentions.

FlowingSpaces | Oil on Linen Panel | 30 x 50 inches

Grossmann’s introduction to oil painting began at an early age with lessons from his grandmother, and took shape during painting classes in Chile that met six hours a week for three years. When he was 14, his family moved back to Colorado, and after high school, Grossmann continued his art education in college. “Honestly,” he says, “art’s been so ingrained in my life, I knew that’s what I wanted to do, if at all possible. I didn’t know what that looked like, but I knew that’s what I wanted.”

Lowering Sun and Fading Autumn Forest | Oil on Linen Panel | 30 x 50 inches

He initially took business courses, giving himself a back-up career should art prove impossible, then enrolled at the now-defunct Colorado Academy of Art in Boulder, where his studies were based on abstraction and esoteric art, not on theory and observation — things he didn’t understand at the time.

After college, Grossmann steadily worked on his craft, which in part included solitary time studying the work of master artists. “I would spend hours poring over Andrew Wyeth’s works and the landscapes of Gustav Klimt — the way he used line and pattern in his images is intriguing. And Egon Schiele, the emotional rawness to his work is captivating,” he says. As he followed one artist’s work, it led to the next discovery. He found the Minimalists and Abstractionists, such as Agnes Martin, and soon became intrigued; he knew this was something he wanted to bring to his own work. “I admire Agnes Martin’s sense of simplicity,” he says. “And the beautiful quiet she imparts.”

Forest Edge in Early Autumn | Oil on Linen Panel | 24 x 18 inches

Painting outdoors, on location, Grossmann formed vital relationships with fellow artists. Jivan Lee, a contemporary landscape painter in New Mexico, recalled meeting Grossmann for the first time nearly a decade ago: “I felt impressed, intimidated, and a bit envious,” Lee says. “There was a powerful presence in his paintings, a restraint, and a sense of almost ferocious commitment to their quality, technically speaking. And they were so sensitive, so respectful to the subjects and the mood of the day.”

Shy by nature, Grossmann’s voice comes alive in his work. “Even though I paint landscapes,” he says, “every painting really is a self-portrait of myself as an artist. They’re portraits of my own emotional responses to the world around me.”

Being reserved, however, might be useful for long hours painting in silence, but it doesn’t always help an artist survive. Yet, Grossmann persisted, staying true to his vision, and soon his work made its way into the greater artsphere. Gallerists and curators started calling, including Jonathan Cooper in London, whose namesake gallery will host a solo exhibition for Grossmann in June 2020.

Fallen Leaf Patterns with Solitary Deer | Oil on Linen Panel | 30 x 40 inches

“In 2015, I was sitting in my gallery going through a catalog that included one of my artists, Michael Austin,” Cooper says. “I turned the page, and there was a landscape painting by an artist I was formally unaware of; his name — David Grossmann. The painting immediately took my eye, and then, looking on the internet, I knew I had found a modern master. This was an exciting, rare moment.”

Today, Grossmann focuses on capturing the essence of his subjects. “For me, it always starts as an emotional spark,” he says. “Most of my process is trying to hang on to that feeling.”

Grand Teton with Pastel Sunset | Oil on Linen Panel | 40 x 30 inches

Winter Horizon with Flying Birds | Oil on Linen Panel | 24 x 18 inches

As Lee put it, Grossmann’s sense of poetry is evident throughout his work. “He composes paintings like I experience haiku: sparse; laden with intention and deliberation; structured; forceful and delicate; bold and yet light like a breath; freeing for his audience.”

In the studio, without the pressure of weather and the movement of the sun, Grossmann takes more time investigating the effects of layering and glazing. “There’s a lot of experimenting that happens in the studio; paintings emerge over time. I usually have multiple paintings working at the same time,” he says. “It’s a good balance, the meditative, in-the-studio work with the spontaneity of the outside.” And though on occasion he takes photos, he rarely uses them. “Photos aren’t helpful; they have such a mechanical feel. So much of my process is about feeling.”

Stylistically, he admits he doesn’t know where he’s going, but that he’s giving himself space to try new ideas. Since reading a biography on Claude Monet, Grossmann is now eager to paint on a larger scale. “Being able to keep some of my work and surround myself visually,” he says, “this is the shadow of my future thought.”

No Comments