11 Jan Imagined Wests

Paul Pletka is drawn to the mysterious. Filled with masked figures and enigmatic rituals, his work is characterized by an obsessive attention to textures and details, from splintered wood and delicate beadwork to human flesh and bones. This tension between sensual surfaces, visible bodies (or parts of bodies), and the secretive aspect of religious rites and cultural encounters forms the substance of Pletka’s art, which exudes a sense of transformation from one world to another, one life to the next.

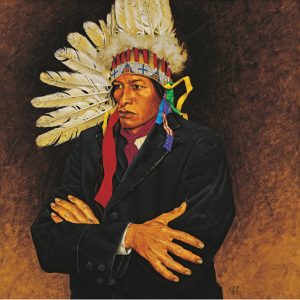

The Delegate, Acrylic on Linen, 40 x 40 inches, 1991, Private Collection

Pletka launched his artistic career, like so many before him, following his first visit to Taos, New Mexico, in 1969. There, amidst the austere landscape and the Sangre de Christo mountain range, Pletka discovered a rich art history, one that dated back centuries and embraced a unique synthesis of Pueblo, Hispanic, and Modernist art traditions. These multiple and overlapping artistic settings, where visible elements of ancient Native cultures and a romanticized Hispanic past sat alongside a vibrant, contemporary art scene, made for an “encouraging and vibrant and intellectual community miles away from the parochial attitudes of my [western Colorado] childhood home.” In Taos, Pletka felt that he “really belonged, and that New Mexico could one day be my home.”

Within a few years, he made another move that would transform his art career. In 1976, he met Nancy Benkof at a Scottsdale gallery, and within a year, the two married and moved to Tesuque, New Mexico (about an hour south of Taos), another austere landscape with a deep sense of history and a centuries-old Hispanic community. Here, Pletka’s dual interests in regional culture and ritualistic drama focused on the Penitentes, a secretive, exclusively male, lay Catholic brotherhood that conducted their rituals largely in private. Shortly after he and Nancy settled into their adobe home in Tesuque, Pletka became aware of the Penitente group … which in turn furthered the artist’s interest in the Spanish incursions into the New World.

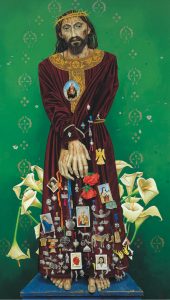

Nuestro Padre Jesus, Acrylic on Linen, 70 x 40 inches, 1998, Collection of Dr. and Mrs. A. K. Hedley

By the early 20th century, the rise of a land-hungry Anglo class in Northern New Mexico had all but eroded the patriarchal system of land holdings within Hispanic communities, creating new generations of landless young men. The brotherhood, with its emphasis on social and personal discipline, thereby also filled a cultural and social void left by the evaporation of traditional male authority.

As he did with Native American culture upon his arrival in New Mexico, following his move to Tesuque, Pletka immersed himself in the ritualistic side of Hispano culture, observing Penitente rituals whenever possible. He and Nancy began collecting Hispanic art, including painted retablos, bultos (similar to retablos), and priest’s vestments. They sought out scholars, collectors, curators, and santeros (makers of santos), and explored local museums, including the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe.

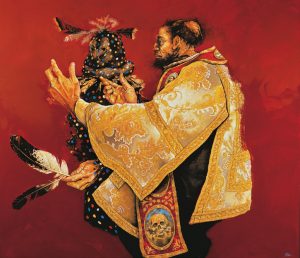

Talks to Gods, Acrylic on Linen, 52 x 60 inches, 1979, Collection of Dr. Larry and Jane Hootkin

In 1981, the couple traveled through Mexico, including Guadalajara, Cuernavaca, and Mexico City, visiting cathedrals, museums, local arts markets, and the murals of Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siquieros. It was a trip that, according to Nancy, had a profound effect on her husband: “This was a language of art that he could understand in his bones,” she says.

The rich blend of Indigenous and Hispanic cultures with Mexican Modernism that Pletka encountered in Mexico, reconstructed in memories and fused with elements of Northern New Mexican ritual, would nourish his work for decades to come. Not long after his Mexican sojourn, Pletka injured his back, resulting in chronic pain that made travel for him (to this day) impossible by plane and difficult by car. With weighted memories and convinced of the importance of Spanish Colonial art, he and Nancy became avid collectors and worked to place key pieces in museum collections.

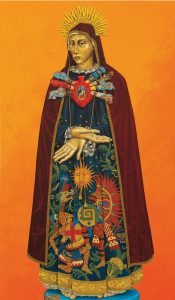

Nuestra Señora de los Indios, Acrylic on Linen, 70 x 40 inches, 1999, Collection of Janis and Dennis Lyon

Pletka also began a process of integrating ritualistic and liturgical elements from both Native and Hispanic societies into his work, a fusion that occupies him to this day. Indeed, this syncretism, in which religious elements of diverse origins are merged to create new spiritual traditions and belief systems, points to the tensions and ambiguities between cultures as well as the legacies of colonialism that helped birth the post-Columbian world.

Syncretism is less about geographic specificity than a visual layering of multiple traditions, subverting expectations of objectified, exotic “others” common in Western religious art. For example, in Looking for Heaven (2001), figures wearing masks of Tlingit origin are given the exact same treatment as the orthodox priest (a self-portrait of the artist) in their midst.

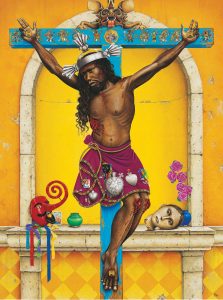

El Señor del Noche | Acrylic on Canvas | 92 x 68 inches | 2009 Private Collection

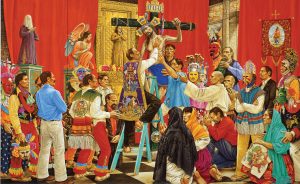

This emphasis on elaborate regalia as both an indicator of cultural difference and a means of crossing cultural boundaries is reflected in what is perhaps one of the most ambitious paintings of his career, Nuestro Señor el Desollado (Our Lord, the One Who is Flayed). In this image, Christ is being taken down from the cross by an eclectic gathering of mixed religious and ethnic persuasion. Subsumed by this colorful crowd, the viewer’s attention is shifted away from the figure of Christ and toward a myriad of details and images within images, such as the scene of Spanish conquest that decorates the priest’s robes or the crest of the Mexican national flag emblazoned on the serape of the man behind him. Throughout, the presence of figures wearing masks of indigenous, folk, and Hispanic origin contribute to the atmosphere of cultural ambiguity and psychological tension that are often the product of conquest and imposed religious authority.

Nuestro Señor el Desollado (Our Lord, the One Who is Flayed) | Acrylic on Linen | 87.75 x 140.5 inches | 2004 Collection of Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Western Art Associates together with numerous individual contributors.

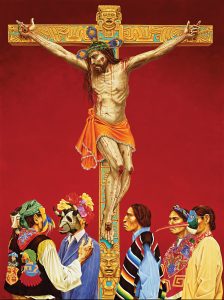

It is perhaps Pletka’s interest in the encounters and exchanges between different cultures and the narratives of appropriation, subversion, and resistance that spring from them that has drawn him to the crucifix, a particularly compelling and oft-repeated image within his oeuvre. Iconic in its instantaneous communicative power, the crucifix as a subject further allowed the artist to explore the ways that Catholic rituals and values were both resonant and resisted within the complex cultural blend of the post-Columbian world. Indeed, throughout the many crucifixion scenes in his paintings, Pletka seems to delight in subverting expectations of both Jesus Christ as a sacred figure and his audience as reverent and faithful.

Consider El Señor del Noche (2010), in which a Black Christ or Christos Negro, a figure common in the villages of Mexico and Central America, wears drapery adorned with Mexican silverwork, and is nailed to a cross embellished with images of conquest and surmounted by Tlacatzinacantli, the Mixtec bat god, identified in ancient codices with death, blood sacrifice, and the night. On the ledge behind sits a folk mask of a Moro (or Moor) and the severed head of a wooden Madonna. What are we to make of this eclectic and seemingly antithetical arrangement of objects and bodies? Africans, imported as Christianized slaves and malarial-resistant replacements for the plummeting Native workforce, formed a substantial demographic within post-conquest Mexico. As a sacred image, Christos Negro was an invention of the Church, designed to help convert a mixed-race population. By 1570, there were already nearly three times as many Africans as Europeans in Mexico, and twice as many of mixed-race status.

Tears of the Lord | Acrylic on Linen | 96 x 72 inches | 2005 Courtesy of the Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles, California | 2012.17.1 ©Paul Pletka

By raising a Black Christ beneath an indigenous god associated with blood sacrifice before broken relics of varied origin, Pletka weaves together three themes, none common to Catholic imagery. These include the complex racial demographics of post-Columbian Mexico; a subversion of Euro-American expectations of the crucifixion and its meaning; and the unexpected parallels between Christian and indigenous belief systems.

A similar, destabilizing effect takes place in Tears of the Lord (2006), in which a group of figures wearing pagan dance masks and a combination of traditional and Western dress appear unaffected by the vision of a crucified Christ within their midst, shifting the traditional balance of power between the deity and the faithful. Rendered as if in a traditional wooden bulto, the figure in Tears of the Lord appears simultaneously dead and alive, scarred by the ravages of time while gushing dark red blood from stigmata wounds. Beneath Christ, figures wearing Moor, bull, and bird masks are overseen by the Aztec rain god Chacmool, who, according to legend, cried as his people were sacrificed to his altar-ego, Tlaloc. Bound together by the loss of a Native son, the Christian and Indian deity face a masked throng whose indifference to the suffering within their midst only serves to amplify the tensions between the various religious and cultural systems at work throughout the painting.

The Lolo Trail | Ink and Watercolor on Illustration Board | 30 x 80 inches | 1974 Private Collection

As an unfolding experiment in ethnic and religious blending, the West today is in many ways the product of the social and cultural encounters that Pletka describes in his work. This ability to see beyond the purely mythic, one-dimensional levels on which the conquest of both land and people is so often portrayed secures for Pletka a relatively unique place in art of the American West, one that celebrates the mystical while breaking down the myth.

No Comments