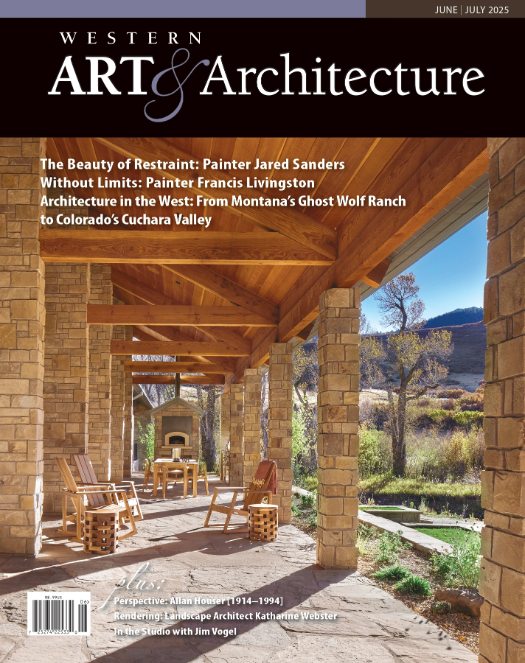

06 Jul Perspective: Visionary and Inventive

Early in his career, R.C. Gorman was staying at the Safari Hotel in downtown Scottsdale, Arizona, before the opening of his solo show at a nearby gallery when he realized there was nothing in the hotel lobby advertising the show. He called his teenage cousin Tazbah McCullah in Phoenix and told her of his dilemma. Tazbah didn’t yet have her driver’s license, but she was game. She skipped school and drove to Scottsdale, picking up the art materials Gorman had requested on the way.

When she got to the hotel, without traditional Navajo clothing for her to model, Gorman pulled off a bedspread and wrapped his young cousin in it. As Tazbah posed, he produced a simple drawing in his distinctive style of gray, black, and a touch of orange. He displayed the finished piece in the lobby, announcing his show. As with all his art over the decades to come, the show sold exceptionally well.

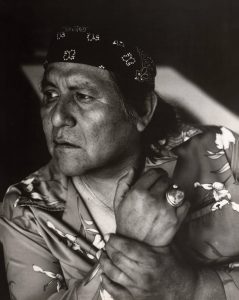

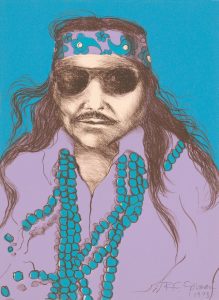

Gorman with Ring | Photograph | Artist and Year Unknown | Courtesy of R.C. Gorman Navajo Gallery

For Tazbah, the story highlights qualities she loved about her relative — his spontaneous, irreverent nature and his warmth and appreciation for family. At the same time, it points to another set of characteristics that contributed to Gorman’s enormous success as an artist. While his playful, people-loving side was well known, it was matched by a seriousness about his work. He had an inherently strong and clever business sense and the spirit and initiative to launch an art career on his own terms.

When he opened the R.C. Gorman Navajo Gallery in Taos, New Mexico, in 1968, it was the first Native-owned and operated fine art gallery in the country. A prolific artist in multiple mediums, including oils, oil pastels, acrylics, lithography, serigraphy, ceramics, and bronze, Gorman rose from an unknown to a sought-out figure whose easily recognizable, internationally collected imagery gained an iconic association with the American Southwest.

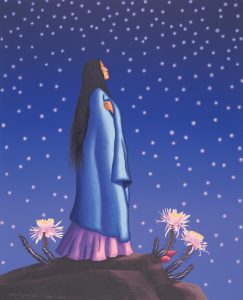

Gracias! | Color Lithograph on Paper | 32.125 x 26.125 inches | 2000 | Courtesy of R.C. Gorman Navajo Gallery

Rudolph Carl Gorman — Rudy, as he was called — grew up on the Navajo Reservation in northeastern Arizona. His great-grandfather, born in 1831, was among the finest early Navajo silversmiths. His father, Carl Nelson Gorman, was a painter, illustrator, and professor at the University of California, Davis, and later joined his son in a number of gallery and museum exhibitions. During World War II, Carl served with a select group of Marines in the Pacific arena. Known as the Navajo Code Talkers, they created and communicated in a coded version of the Navajo language, which the Japanese were never able to break.

As a boy, Rudy drew on whatever surface he could find, including the walls of the family home near Chinle, Arizona. When out herding sheep with his aunt, he would draw in the sand and on rocks and form shapes out of clay. Throughout his life, he credited the strong women around him, especially his grandmother, aunts, and a high school art teacher, with supporting and encouraging his interest in creativity.

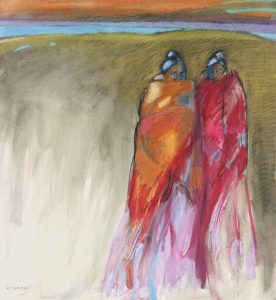

Best Friends | Oil Pastel on Paper | Size Unknown | 1966 | Courtesy of R.C. Gorman Navajo Gallery

Rudy’s cousin Grace McCullah (Tazbah’s mother), recalls Rudy as an artistic mischief-maker in high school. McCullah, now 91 and living in Taos, remembers sitting near Rudy in class; and, when the teacher’s back was turned, they drew pictures and tossed them to each other. Appropriately, the drawings were of women — famously the focus of Gorman’s art years later. After Gorman moved to Taos, Grace was his primary model for 36 years. As he drew, they chatted and often reminisced about their teenage years, McCullah says.

Following high school, Gorman served in the Navy, earning a little cash by drawing pin-up pictures of sailors’ girlfriends. After leaving the Navy, he studied literature and art at Arizona State College (now Northern Arizona University), where he was given an opportunity that impacted his art for the rest of his life. The Navajo Tribal Council awarded him the first scholarship for a tribal member to study for a year at a foreign university. He chose Mexico City College.

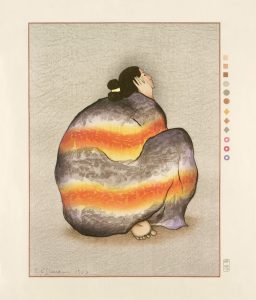

Monica | Woodcut in Colors on Paper | 23 x 18.75 inches | 1982 | Courtesy of R.C. Gorman Navajo Gallery

There, he was introduced to the work of Mexican masters, including Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. Along with vivid colors and powerful forms, Gorman took note of the painters’ subjects. “Here were these great Mexican artists painting women grinding corn and working in the fields. I thought: This is just like my people,” Gorman said in a 1994 interview. The experience encouraged stylistic freedom and opened the door to depicting the strong, beautiful women of his culture.

Upon returning from Mexico, Gorman studied art at San Francisco State University and began his professional career exhibiting at a gallery in the city. Then in 1968, after having first visited Taos four years earlier, he borrowed money from his father and purchased a former gallery in a historic Taos adobe. He moved there and opened the Navajo Gallery. The gallery’s inaugural show featured Native artists that went on to international acclaim, including Pablita Velarde, Helen Hardin, and Charles Lovato. (Today, the Michael Gorman Gallery in Taos is owned by Gorman’s nephew. It carries work by R.C. and other artists in the family.)

Self Portrait St. I | Color Lithograph on Paper | 13 x 9.65 inches | 1973 | Courtesy of R.C. Gorman Navajo Gallery

Initially, the Navajo Gallery also served as Gorman’s home, and hours fluctuated according to the artist’s schedule. In a 1998 essay, longtime Navajo Gallery director Virginia Dooley recounted that “Anyone drifting in could easily be invited to dinner, sold a painting, or be asked to step gingerly around his pet pig, iguana, or skunk.”

When that space became too crowded, Gorman bought another old adobe and remodeled it as his home, expanding it to include an enormous studio, indoor swimming pool, Japanese-style sculpture garden, and room for his personal art collection, including works by Picasso and Chagall.

As Dooley’s description suggests, the boundary between Gorman’s professional and social life was virtually nonexistent. Gregarious and epicurean, he loved food and was ready to host a lively party or dinner for patrons and friends. His sister, Zonnie Gorman, put it this way: “You know how when you walk into a crowded room, and there’s that one person who draws your attention and stands out, in a good way — that was R.C. He was very flamboyant, larger than life.”

Numerous celebrities and public figures visited Gorman and collected his art. Among them: Elizabeth Taylor, Jackie Onassis, Alan Ginsberg, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, Gregory Peck, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Andy Warhol. Warhol also hosted Gorman in New York City, and the two exhibited work together in a 1978 show where they were jokingly referred to as “the odd couple.” As different as they were, the pair had a keen sense of self-promotion in common, which in Gorman’s case manifested in such phenomena as a series of cryptic billboards along the interstate between Santa Fe and Albuquerque, each one in bold letters simply asking: Who is R.C. Gorman?

De La Noche | Serigraph | 29 x 38 inches | 1991 | Courtesy of R.C. Gorman Navajo Gallery

For many, the answer was artwork as appealing as Gorman’s public persona. Focusing his realist skills on his models’ faces, hands, and feet, he abstracted the rest of their forms and backgrounds in simple, graceful lines and warm colors.

Bob Sahd, owner of the R.C. Gorman Navajo Gallery, purchased the artist’s estate and operates galleries in Scottsdale and other locations. He cites the timelessness of the imagery and observes that people encountering it often appear emotionally moved by it.

Andrea Hanley, chief curator at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe, has a similar view. In 1975, the Wheelwright honored Gorman by featuring him first in a series of exhibitions on contemporary Native artists. Hanley is distantly related to Gorman and believes the attraction to his art is related to its universal qualities. “Even though the subject matter and artist are Navajo, it speaks to things that are human and universal. Everyone can feel and connect with them — the beauty and strength of women, and connotations of mother, sister, and daughter,” she says.

Winter’s Child | Color Lithograph on Paper | 30 x 34 inches | 1991 | Courtesy of R.C. Gorman Navajo Gallery

Gorman had marked another first milestone two years earlier when his work was exhibited in Masterworks from the Museum of the American Indian at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. He was the only living Native American artist included. A New York Times reviewer called him “the Picasso of American Indian art.”

Although some critics over the years have dismissed Gorman’s work as decorative and commercial, others believe this attitude ignores the importance of his role in art history. Along with Fritz Scholder, T.C. Cannon, and other Native artists of the late 1960s and ’70s, Gorman was “taking ownership of Indigenous imagery,” notes Christian Waguespack, Head of Curatorial Affairs and Curator of 20th Century Art at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe. Gorman was not only forward-thinking in eliminating the non-Native middleman from the sale of his art, he was also “depicting Native people with love, affection, pride, and dignity, rather than as ‘other,’” Waguespack says.

By all accounts, it was a genuine love that extended beyond his people to those from all cultures and walks of life. It was also an unabashed love of life itself, expressed through his art and the “cheerful extravagance” of his lifestyle, as Dooley put it. Or, as Gorman himself said, likely with his head thrown back in laughter: “I’ve never gone for the string quartet. I prefer the whole orchestra!”

No Comments