01 Feb Collector's Notebook: Frozen in Motion

My father, the sculptor Burl Jones — back when he was still feeling his way as an artist — spent a number of weekends at art auctions, county fairs, trade shows. It was a family business, and we were right there with him. Dropping down the tailgate, my brother and I would wrestle bronzes from truck bed to booth, waddling along quick to where Mom had covered a card table with black cloth. To carry the largest pieces, you jammed your fingers into crevices of cold metal, found the least-cutting spot between fringe and arrowhead, lifted with your legs and let it sit at the waist. Thirty, 40 pounds of mule deer and elk, mountain men and Indians. Plug in the clip lights and sit back with a novel, wait for customers. If it was an arts fair or some such, you might find your booth wedged between crocheted knick-knacks and a fry bread stand. The pedestrian browsers, bless their hearts, always had the same old comments. “Look at that detail.” Sometimes: “Does he carve right into the metal?” And always: “How long’s it take to make one of these things?”

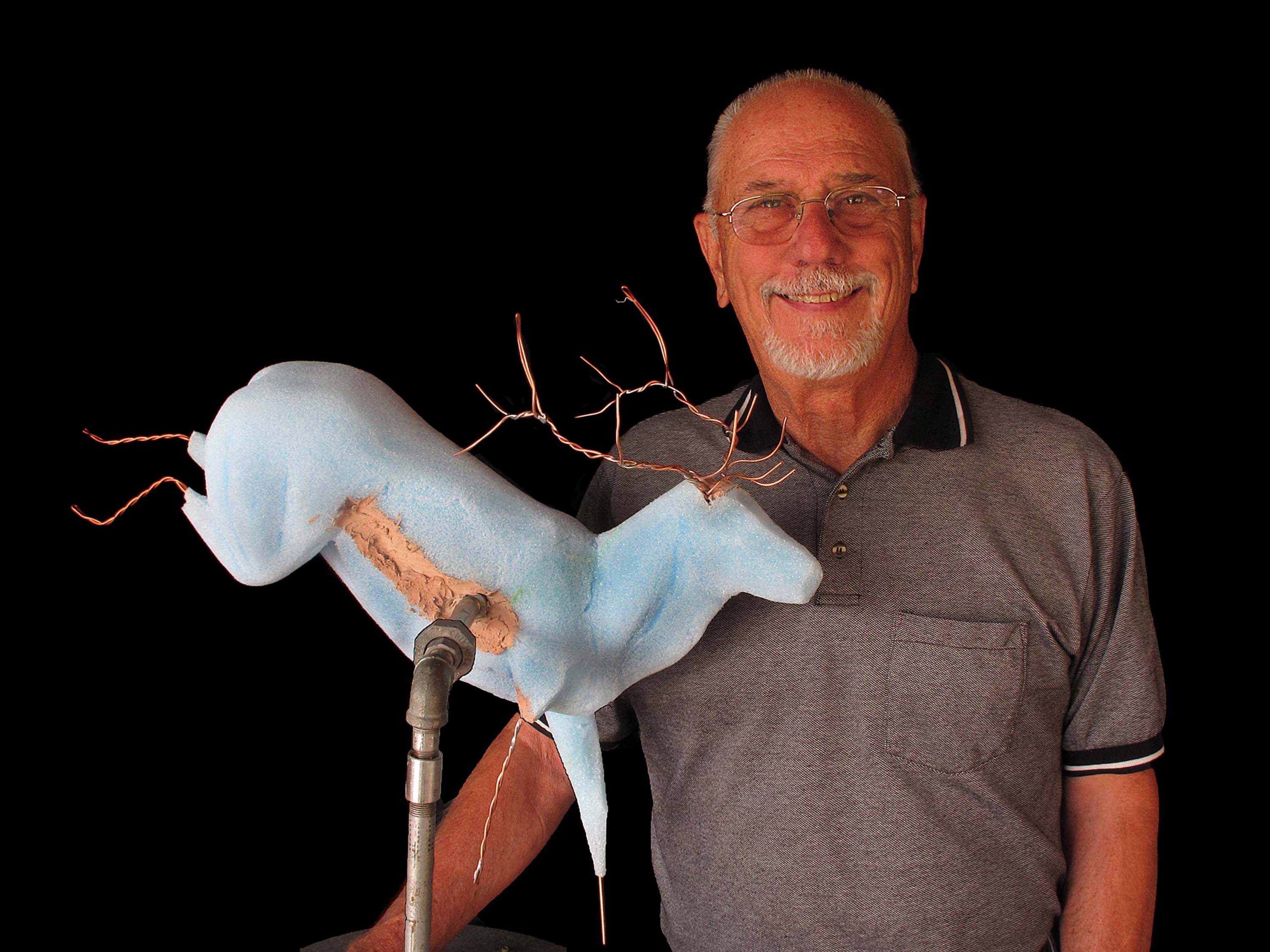

A tough question, it turns out. A medium-size sculpture might involve several weeks of Dad hunched over a foam armature, rotating it on a turntable, pinching up chunks of clay, trimming them away again. Stepping back, squinting, reconsidering. But then there were the years of determined self-education preceding those three weeks. How do you account for those? And what about the foundry? The guys that cast the bronze, who take Dad’s clay sculpture and transform it into metal. What about those guys?

In his early years, Dad struggled to find a foundry he liked. Initially, he’d used outfits on the East Coast, but they were finally too… dilettantish, if that’s a word. Ignorant of the American West such that they would take it upon themselves to replace his prairie dogs with fox squirrels. Once he began using foundries in Montana, though, things fell into place. He’d drive to Kalispell, Bozeman, Billings, drop off his clay, then repeat the trip a few months later, returning with a bronze. For a 12-year-old kid, it seemed on the cusp of magical. How’d they do that?

Unless an artist casts his own work, by the time a bronze sculpture hits the gallery it’s been touched with care by seven or eight different sets of hands. It’s been the object (for a medium-size piece) of roughly 30 hours of collective labor, and gone through at least 12 distinct stages of production, mold to wax model, wax chasing and ceramic investment, pouring and patina.

Located outside of Bozeman, Montana, Northwest Art Casting has been creating bronze sculptures since the late 1980s. Dad’s been with them pretty much since the beginning, as have a number of other sculptors. Scott Billis, one of three owners, said, “I send out over 150 Christmas cards, but we work consistently with about 50 artists.”

Driving by, the place is easy to miss. A couple of nondescript metal buildings, exterior staircases, ceiling vents leaking steam. Inside, however, it’s an oven-warmed, congenial mash-up of high-school metal shop and artist’s studio. Smells of hot solder and melting wax, a reassuring cacophony of grinders and compressors, ratchets and clanging metals. A dozen different employees working under thumb-tacked photos of grandchildren and trophy bulls. Here’s what happens when you give like-minded artisans a paycheck and some autonomy, turn them loose on a common job.

Over the course of several weeks, I followed Dad’s most recent sculpture — a running bull elk, a study in form called Escape — through the gradual process of its transformation, clay to bronze. I made five trips to the foundry, dropping in as his sculpture bounced its way through the work stations. With the indulgence of Northwest Art Casting, I was finally, all these years later, going to see how they do that.

Every bronze sculpture cast via the lost wax technique starts off with a rubber mold. A cup of liquid rubber and fixative, an artist’s brush to paint it on with. If the sculpture is any size at all, it’s already been cut apart into segments: head and shoulders, hindquarters, antlers, base. (Molten bronze will settle at the low spots in a mold, but miss the high areas. Every complicated jig or jag, set of antlers or raised leg, needs its own separate mold.)

I watched Matt Bicknell, one of the other owners of Northwest Art Casting, paint rubber onto the elk, then later, slather on handfuls of plaster of Paris. “These square tabs in the rubber, those are registration marks. They’ll help the plaster stay in place, help us fit it all back together again later.”

After the mold had a chance to dry, was disassembled and pieced back together again to create a wax reproduction, Dad’s original sculpture was tossed aside, a ruin of cracked clay and fragmented foam. The wax model, how- ever, as it emerged from the mold, was a near-duplicate of Dad’s original work. Near, but not quite. It still had certain flaws, including a seam line where the mold had joined. The next stage in the process — wax chasing — would correct these errors.

Elaine Reinhardt sat with a wood-burning tool held like a pen, touching Dad’s elk here and there. “I’m looking for bubbles, pits, seam lines,” she said. “I’ll pay a lot of attention to the detailed stuff. The eyes, ears, teeth. Some of it you have to rebuild.”

From wax chasing, Dad’s elk next went to Jeff Van Soest, the third owner of Northwest. Jeff’s work involves attaching the sprues that would serve as outlets for the wax cooking out of the investment, as well as the wax cups that would work as funnels for molten bronze. “This is where we decide how we’re going to cast it.”

Sprues and cups attached, Dad’s elk went to the slurry room to be dipped into a liquid the color of green-apple bubblegum, coated over with a layer of white sand and set aside to dry. The ceramic investment would finally be made up of eight or nine layers of this mix.

After drying, the investments went across the parking lot to the burnout oven, where they were cooked at 1,400 degrees. The wax drained out into a catch basin, and the investments, emptied, were carried with oven mitts to a rack near the foundry’s smelter.

And this… this was what I’d had in mind when I asked Northwest Art Casting for a tour. Smelter, pouring, casting. A flare of flame around the crucible and a glowing, lava-thread of molten bronze over ceramic cups. Ten minutes of heat-shielded aprons and masks, two men carefully tilting the crucible over the ceramic investments. You could feel the heat from 20 yards away.

After the metal cooled enough to remove the investment, the bronze segments were sandblasted clean and sent to a welding station to be pieced together again. Finally, the assembled bronze elk went to patina. Under instructions from Dad, artist Isaac Lowe heated the metal with a propane torch and, gradually, over the course of several hours, coated it first with liver of sulfide then ferric nitrate. He spritzed water on the metal to judge its heat. “The hotter the bronze, the redder the ferric gets. Cooler, it’s more golden.”

A few days later, Dad placed his newest sculpture on the kitchen counter. He rotated it slowly, studying it through bifocals. This would be his final approval before passing it along to one of the Western galleries that handle his work. Perhaps The West Lives On in Jackson, or Creighton Block in Big Sky or the Devin Gallery in Coeur d’Alene. He considered the patina, the hidden welds. “Well?” he asked me.

“Man,” I said. “It’s a good one. Dad, that’s beautiful.”

Ephemeral clay to eternal bronze, despite the collaborative aspects of the casting process, any given sculpture still belongs to the artist. Over the last 40 years or so, my father’s created more than 200 sculptures. A body of work that, in sum, reflects a singular set of preoccupations. A lifetime after the county fairs, after the years in his own gallery, after the collectors and the university commissions, Dad’s carved out a place of his own in the larger landscape of American sculptors. There is a certain style that belongs uniquely to Burl Jones. His latest piece, this leaping elk — with its frozen motion, its potential energy — is his and could be no one else’s. But good art also ultimately belongs, in some measure, to the viewer. To study an art piece, to interpret it, is to briefly possess it. Given the work of the foundry, Escape is now partially ours as well.

A good foundry does not create the art, it’s true, but they do enable the artist. They help with that most-essential of transitions, his to ours.

- The first stage of casting a bronze sculpture is to create a rubber mold. The typical rubber mold is composed of three discrete layers of rubber, with a period of drying between each layer. The first layer is called the “print layer,” and is usually a thinner rubber that can pick up every detail. After the rubber mold dries, plaster is added to lend stability.

- Whatever flaws are inadvertently introduced to the wax model — seam lines where the mold comes together, for instance — are cleaned up or “chased” by hand.

- An Exacto knife is used to Carefully cut apart the rubber mold, allowing extraction of the clay original. The cleaner the foundry can make this cut, the less work they’ll have to do later when it comes time to “chase,” or repair, the wax.

- The ceramic investment is created by dipping the wax into a liquid slurry then coating it with a fine grain sand. As many as eight or nine coats of sand may be used before the investment shell is complete.

- From clay sculpture to finished bronze, there are more than a dozen distinct stages of production. Seven or eight different craftsmen played some part in the production of “Escape.”

- The bronze metal (primarily copper) heated to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, is poured into the funnel cups of the ceramic investment, filling the negative space previously occupied by the wax.

- A chemical patina permanently colors the bronze . An open flame heats the bronze, opening pores in the metal and making it more receptive to the chemicals. From a base layer of potash, or “liver of sulfur,” further chemicals are then applied.

- Enes began his career working in wax, but soon transitioned to sculptor’s clay.

- The mold is used to create a wax positive, a model of the original clay sculpture. The wax incarnation of the piece will be used, in turn, to create a ceramic investment into which the bronze will be poured. The rubber mold retains an astonishing level of detail.

- The final ceramic shell, prior to being cooked in the burnout oven, shows only a rough approximation of the finely detailed sculpture inside. before being placed in the oven, trimming the bottoms off the ceramic investments will allow the wax to drain more readily. The investments will eventually be cooked at roughly 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit.

- The segments of the bronze, poured separately, are welded together to form a complete sculpture. The weld seams, not unlike the wax seams, need to be “chased” in order to accurately reproduce the artist’s original texture.

No Comments