12 Nov Perspective: Robert Lougheed [1910–1982]

One day toward the end of his life, Robert Lougheed stopped by the Santa Fe home of painter Wayne Wolfe to see the younger artist’s entry for that year’s Prix de West show. It was a painting Wolfe had been working on for some time and about which he felt good. Other artist friends, including Tom Lovell and Wilson Hurley, had given it nothing but praise and predicted that it would receive a top award. Lougheed carefully studied the painting and then turned to Wolfe. “You’ve worked very hard on that, and it shows. You didn’t enjoy yourself enough,” he offered in his soft-spoken, gentlemanly manner. “Why not repaint some of it and this time have some fun?” At first Wolfe was disconcerted, unsure what the older artist meant. But he repainted some areas in Antlers In The Aspen, depicting four bull elk beside a stream in snowy aspen woods. The painting turned out even better and earned the 1982 Prix de West’s prestigious Purchase Award.

If anyone knew how to enjoy painting, it was Bob Lougheed (pronounced LOCK-heed). Artist friends who painted near him on location remember him frequently exclaiming, “Isn’t it wonderful!” and, “It’s like being paid to eat ice cream!” His wife, Cordy, was quoted once as saying that when someone asked her husband what he would do if he was given a million dollars, he replied he would “probably take a day off and go painting.”

Lougheed’s delight was matched by an absolute commitment to his craft. Throughout his 72 years, the artist never stopped honing his ability to quickly and deftly draw or paint anything in front of him. His dedication, intensely focused observation and ceaseless practice, along with the joy he clearly experienced in the creative process, earned him the deep respect and admiration of countless fellow artists, both during and after his lifetime. Not surprisingly, the paintings that resulted received notable honors, including the Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, and numerous gold and silver awards from the Cowboy Artists of America and the National Academy of Western Art.

Despite the national awards and recognition from his peers, Lougheed was not a self-promoter, and during his lifetime he remained a step or two behind his better-known contemporaries in attention from collectors. “I think he was overshadowed by some of the ‘stars.’ Sometimes it takes time for the cream to rise to the top, but he will be one of those guys who endures,” predicts B. Byron Price, director of the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma. Price is the author of Lougheed, A Painter’s Painter: The Life and Art of Robert E. Lougheed.

A major exhibition of Lougheed’s work opening in November at Nedra Matteucci Galleries in Santa Fe aims to reposition the artist’s star within the galaxy of American painters. Robert Lougheed: A Brilliant Life in Art is on view November 14 through the end of the year. The show was thoughtfully curated from an important collection assembled by the artist’s close friend and art connoisseur, the late David Smith of Santa Fe. Lougheed and Smith enjoyed a deep, decades-long art conversation that resulted in a large and comprehensive collection featuring early sketches, refined drawings, watercolors and oils.

“With purpose, Lougheed chose Santa Fe for his lasting home. Here he found the natural beauty that was at the heart of his inspiration and an arts tradition where he could share his love for painting. It is an honor for the gallery to introduce him once more, among his peers throughout time, in Santa Fe,” says gallery owner Nedra Matteucci. “We hope to deepen the awareness, understanding and appreciation of Lougheed’s incomparable contributions to art across the spectrum, for students of art, collectors, artists and any art enthusiast who has ever hoped to know the feeling of artistic transcendence,” she says. The exhibition reflects the broad range of places and subjects the prolific, well-traveled artist sketched and painted over the years.

The first of those places, and one that played a central role in shaping the Canadian-born painter’s character and art, was the family farm in southern Ontario where he grew up. Born in 1910, Lougheed was the middle of three sons who spent their days working with their father in an era when fields were plowed and wagons were pulled by teams of Clydesdale or Percheron draft horses. It was the beginning of Lougheed’s lifelong obsession with painting horses.

In Follow the Sun: Robert Lougheed, author Don Hedgpeth quotes the artist recalling those boyhood years: “I always had a pencil and notebook with me. When I helped unload the hay wagon, I was forced to quit periodically while my father or brother, in the barn loft above, stowed the hay. During these waits I would draw the horses … I remember saying to myself when I was 12 … I wonder if I could make my living at being an artist, because I enjoy it so much.”

Lougheed took a step toward that goal at age 13 by signing up for a Toronto-based art correspondence course. Following high school and an unsuccessful minor league hockey tryout, he put together a portfolio and set off for Toronto, where he worked as an illustrator for the Toronto Star newspaper. There he spent time with other illustrators and artists and enrolled in oil painting classes at night at the Ontario College of Art. In 1935 he met and began a lifelong friendship with painter John Clymer, who encouraged him to go to New York. It was a turning point in Lougheed’s life.

At the Art Students League of New York, acclaimed painter Frank Vincent DuMond became an extremely influential instructor and mentor, introducing the young artist to plein air painting. DuMond’s students over the years also included Norman Rockwell, Georgia O’Keeffe and John Marin. From then on, Lougheed was firmly committed to working from life, which he described as the “foundation of all worthwhile painting … directly from nature.”

During World War II, Lougheed enlisted in the Royal Canadian Army. Stationed outside Montreal, he spent all his free hours painting outdoors on nearby farms, sometimes in temperatures well below zero. During that period, he was granted time to study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montreal. A long and successful freelance illustration career followed, during which he created such iconic logos as Mobile Oil’s red Pegasus and produced countless illustrations for magazines including The Saturday Evening Post, Reader’s Digest, Sports Afield and National Geographic. But painting remained Lougheed’s first love. For years he limited commercial work to six months a year and reserved the other six months for fine art — although in his case the distinction between the two was never wide.

In 1960 that gap narrowed even more when National Geographic commissioned him to paint various horse breeds around the country, an assignment that took him to the 300,000-acre historic Bell Ranch in northeastern New Mexico. Returning each fall, Lougheed reveled in the Western landscape and the chance to paint the ranch’s dozens of American Quarter Horses from life.

“He just loved horses, and made every animal an individual. It’s something that distinguishes his work,” Price says. Indeed, Lougheed was legendary for painting horses wherever he found them. His friend, Clymer, once told another artist, “There is one thing I must say here and now: Don’t go painting with Bob unless you like to paint horses.”

Lougheed’s mastery of the Western art genre led to his election into the Cowboy Artists of America (CAA) in 1967. He was also a key figure in the establishment of the National Academy of Western Art in 1973. “With Bob there were no gimmicks, no smoke and mirrors, nothing to hide. It was all about putting in your time, all about creative truth,” says Bill Rey, owner of Claggett/Rey Gallery in Vail, Colorado, which represented Lougheed and owns the late artist’s estate. “There’s such a rich authenticity to his work, in color and idea. That’s why so many artists today have Lougheed in their visual vocabulary.”

In 1970, Bob and Cordy settled in Santa Fe, the place that remained home base for the rest of his life and from which he struck out on painting trips around western North America, Hawaii, the Virgin Islands and Europe. Every fall for several years, Lougheed and other accomplished artists gathered to paint wildlife and landscapes at the Okanagan Game Farm in British Columbia, inviting younger artists to join them. Among the most prominent of these were Wayne Wolfe and Santa Fe-based painters John Moyers and Terri Kelly Moyers. John and Terri met there in 1979.

The gatherings reflected Lougheed’s strong interest in working with and encouraging young artists, which he did on an informal basis throughout his life. “Watching him work from life was amazing. I don’t know if I will ever see another artist do what he could do when he set up a paint box,” John Moyers remembers. He also recalls once showing Lougheed a painting that included a piñon tree. “He asked if I had done it from life, and he knew I hadn’t,” Moyers says. “He said he’d been painting 50 years and couldn’t do a tree out of his head, so what made me think I could? That was a good lesson that I’ll never forget.”

Lougheed’s lessons were always delivered with fairness and kindness, however, and often with what Wolfe describes as an “ego sandwich” — two positive remarks on the outside and a negative on the inside. “He didn’t tell you what to do, but he helped you to see for yourself how to do it,” Wolfe says. Then he adds, “I still go to school every day on the advice he gave me. He still paints through all of us.”

- “Deer in Sangre de Cristos” | Oil on Masonite | 12 x 24 inches | 1974-75

- “North of the del Nortes” | Charcoal | 11.5 x 23.5 inches

- The artist with his work

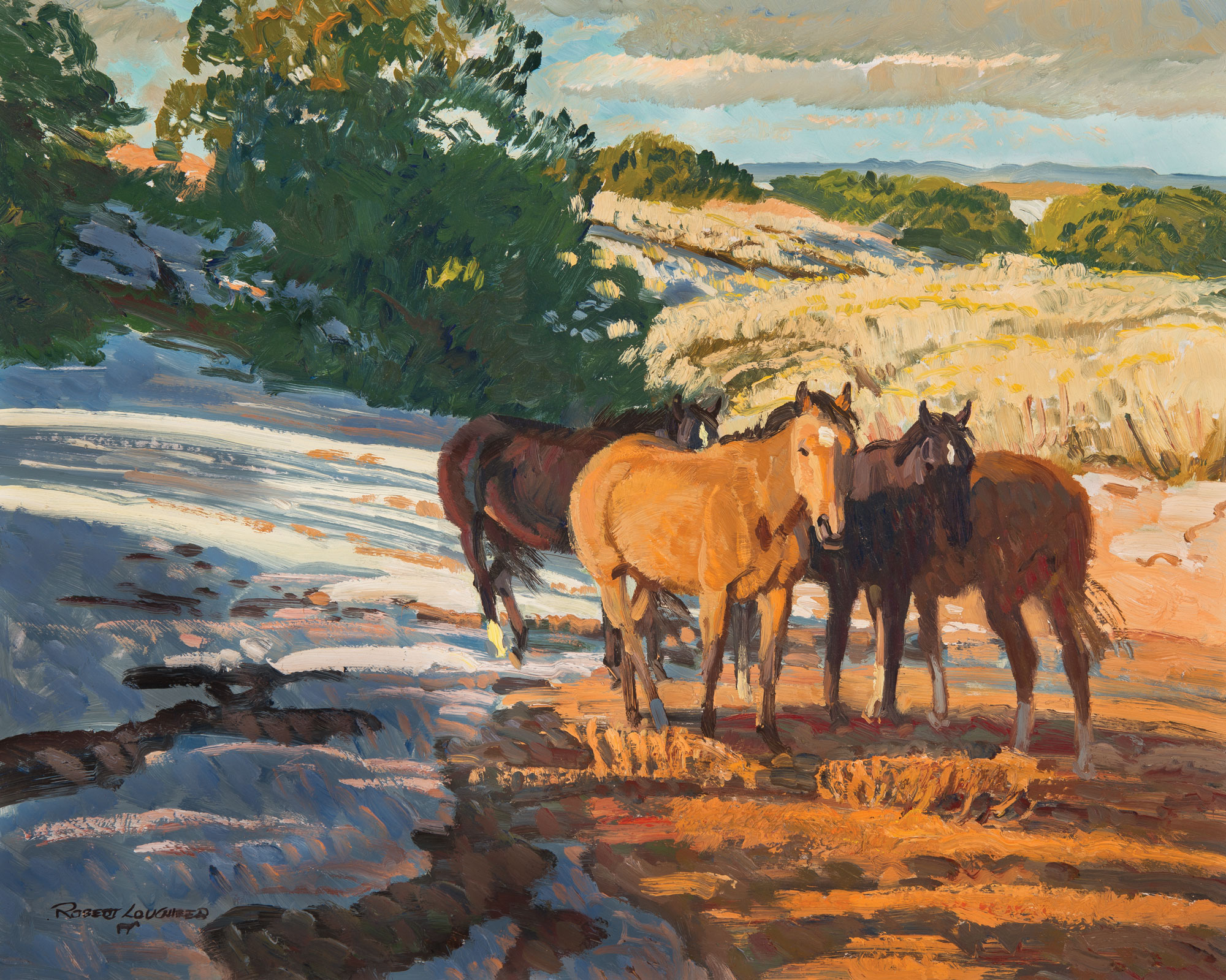

- “Waiting for Spring” | Oil on Masonite | 16 x 20 inches | 1974

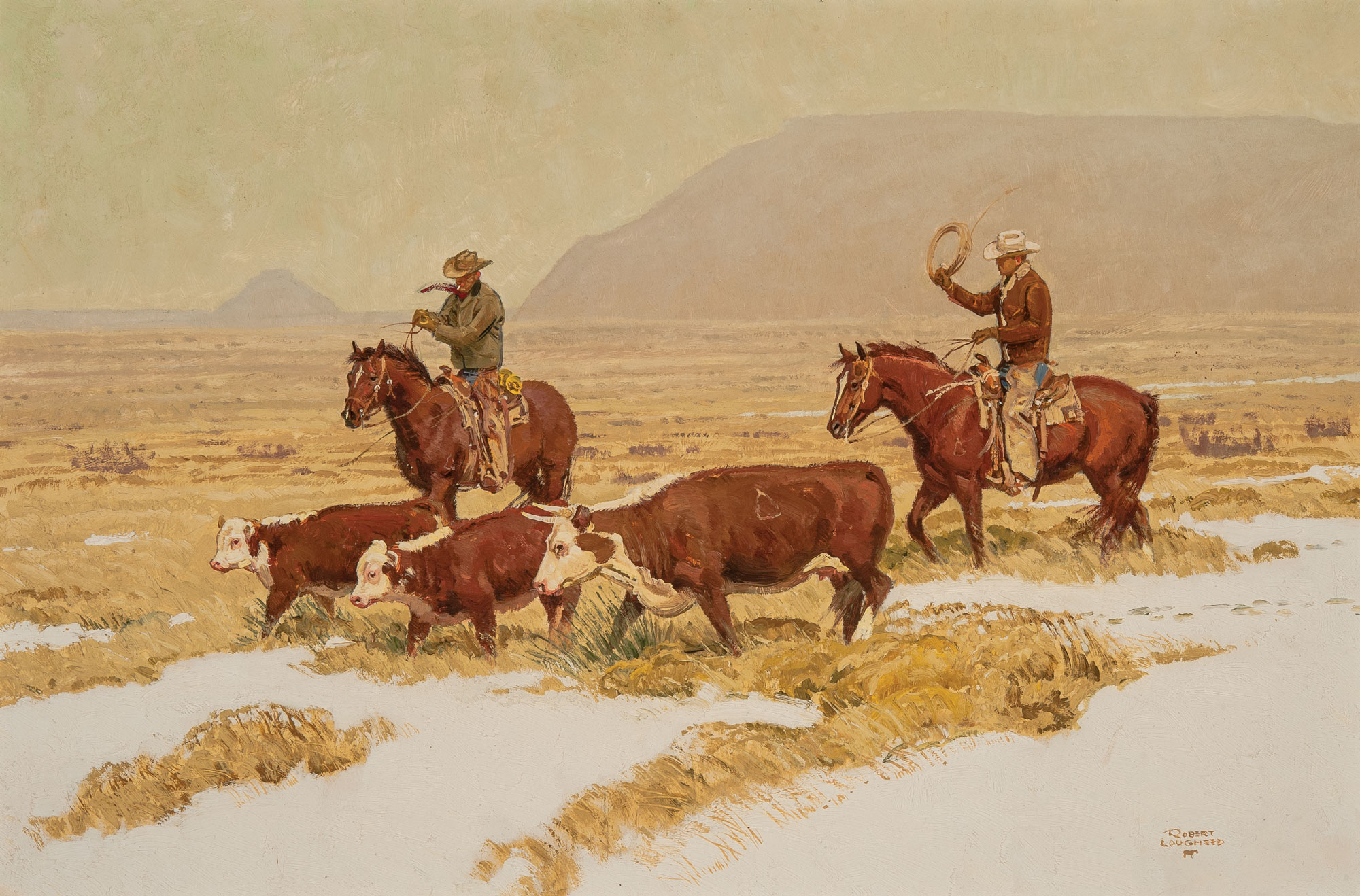

- “Gathering the Strays” | Oil on Panel | 20 x 30 inches | circa 1965

- “Winter’s Work” | Oil on Board | 8.5 x 10.5 inches

No Comments