10 Mar Perspective: Seth Eastman [1808–1875]

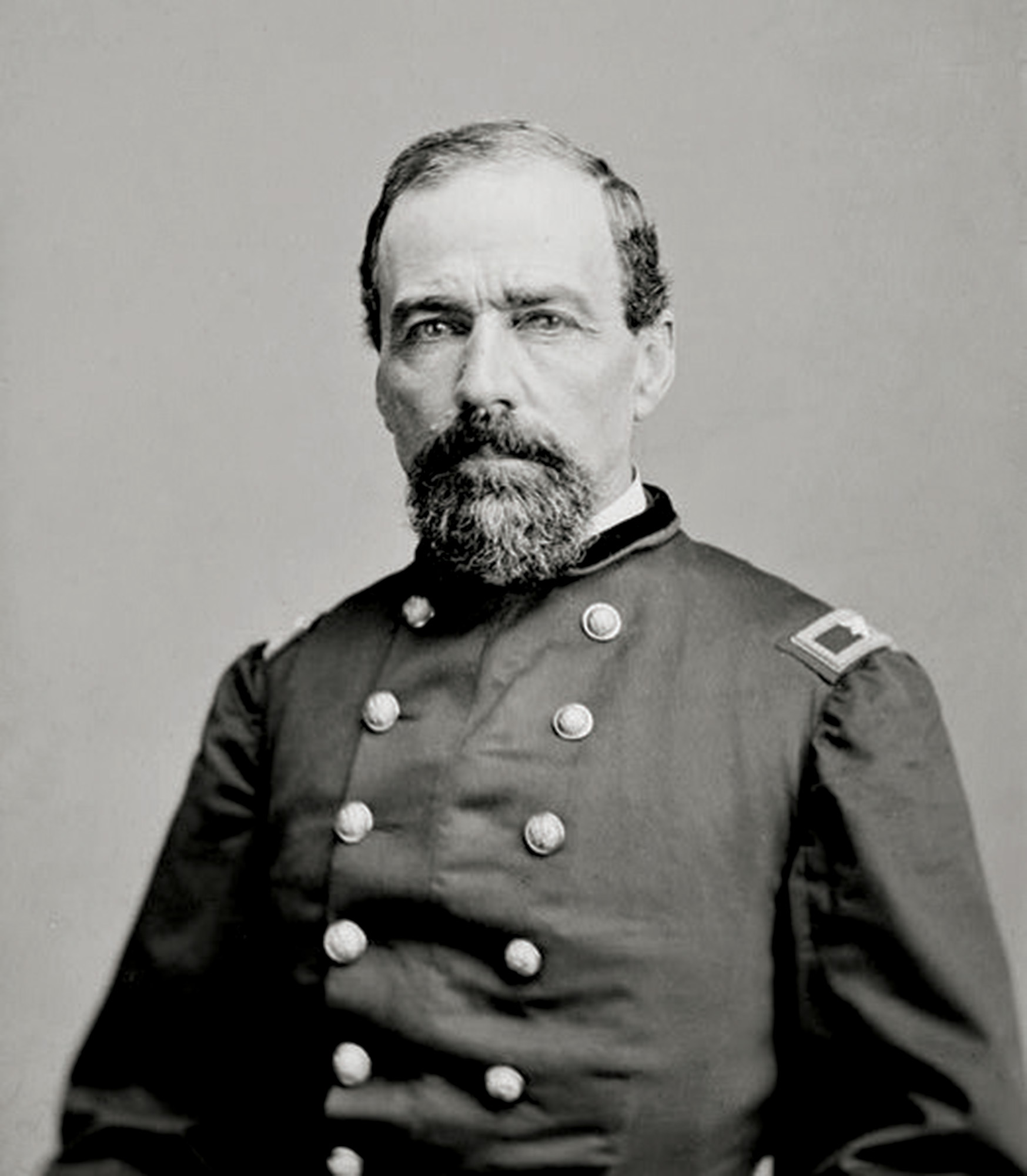

He was a man of contradictions: a career soldier and an artist, an occupier of Indians’ land, a conqueror and a celebrant of their lives. He was a military cartographer who painted some of the most delicate watercolors of the early 19th century. He was a soldier at a fort deep in Sioux territory, yet an affectionate chronicler of his enemy’s traditions. He was a New England aristocrat and West Point graduate who admired the culture of Native Americans so much that, as a young lieutenant, he wed a Sioux woman, with whom he had a daughter. He was a northerner who cherished people of color, yet took for his second wife a southerner who wrote Aunt Phillis’s Cabin, the most widely read, pro-slavery creed of the pre-Civil War era. He was Brevet Brigadier General Seth Eastman [1808–1875], an artist praised during his life, but whose reputation would be eclipsed by that of George Catlin, Karl Bodmer, Edward Curtis and others.

“His are not the sort of grand paintings you would pull up in an American art survey course,” says Felicia Wivchar, curatorial assistant for the House Collection of Fine Art and Artifacts at the U.S. Capitol. “But they’re done with a certain degree of skill.”

Wivchar — a slight brunette who, in her late 30s, is arguably the preeminent Eastman scholar — has led me from the ground floor of the House, beneath the Capitol’s Rotunda (where tourists have filed past in ranks), through a tunnel beneath Independence Avenue to Congress’s Longworth building and into a hearing room once reserved for the House Committee on Indian Affairs.

“In 1867,” she says, “Eastman was commissioned to make nine paintings for the committee’s chamber, which was where people were sitting and deciding on policy toward Native Americans.” The paintings would be “a visual representation of these cultures,” she adds. “The impetus behind wanting to document them was the belief that these cultures would be fading into obscurity.”

Eastman understood Native American culture well. He served at Fort Crawford, near Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, in 1829, and he served at Fort Snelling on the Mississippi River near present-day Minneapolis from 1830 to 1832 and again from 1841 to 1848.

Fort Snelling was the frontier. It was the army’s northwestern-most post, surrounded by Indian encampments. The Dakota Sioux were friendly; the flow of pioneer settlement was but a dribble. Eastman had a daughter by his Indian consort, Stands Like a Spirit, during his first tour here. He began sketching in watercolor, first landscapes then every facet of Dakota and Chippewa life.

When Eastman returned to Fort Snelling in 1841, he was married to the Virginia-born Mary Henderson Eastman, who researched and wrote her book, Dahcotah: Or, Life and Legends of the Sioux Around Fort Snelling, complete with 21 illustrations by Captain Eastman, at the military post. By 1846, while commandant of the post, Eastman had completed some 400 drawings and paintings. A visiting artist, Charles Lanman, said Eastman’s portfolio was “the most valuable in the country, not even excepting that of George Catlin.” He dubbed Eastman a “soldier-artist of the frontier,” one who had committed to “the study of the Indian character, and the portraying upon canvas of their manners and customs,” according to an essay by Particia Condon Johnson in the book Seth Eastman: A Portfolio of North American Indians.

“He did not fall into the trap of romanticizing the Indian,” wrote publisher and Eastman collector W. Duncan MacMillan in the book’s preface. He “set out to preserve a visual record of Indian life, which was then undergoing rapid change.”

An element of change was the growing resentment of Indians toward settlers throughout the Midwest, especially near Fort Snelling. Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act had been implemented, and unfair or broken treaties were common. In 1862 the war of the Sioux Outbreak occurred in Minnesota, during which settlements were attacked and numerous settlers were killed by Santee Sioux. Three-hundred-and-three Indians were convicted and 38 hung in the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Soon after, the Dakota were relocated and Plains warfare began.

It was during this period that Eastman painted the nine House canvases — his recollection of a more peaceful era.

A near Edenic passivity is evident in these oils. Their titles describe their subjects well: Rice Gatherers; Feeding the Dead; The Indian Council; Indian Woman Dressing a Deer Skin; Buffalo Chase; Indian Mode of Traveling; Spearing Fish in Winter; Dog Dance of the Dakotas; and Death Whoop. With the exception of the latter, which portrays a scalping, they depict domestic scenes. As Sarah E. Boehme, of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, notes in Seth Eastman: A Portfolio of North American Indians, they “form a cycle” and are “depictions of the manners and customs of the Dakota as Eastman knew them from the 1840s.”

And they are unique to the U.S. Capitol. As Wivchar has written in a federal history essay, “To a modern viewer, Eastman’s sympathetic and naturalistic approach appears to contrast fundamentally with that of the other Capitol artworks that extolled white supremacy and Christianization of American Indians.”

Oddly, from a soldier’s hand, the paintings eschew warfare as subject for ritual and work. Rice Gatherers, for instance, shows Chippewa women in a marsh batting rice grains into a canoe, the figures classically grouped in an amber light. Indian Mode of Traveling shows a family on foot and on horseback, dragging a travois. Spearing Fish in Winter depicts a group of Dakotas fishing through ice in a composition that mimics Dutch sketches of communal skating. Dog Dance of the Dakotas shows Indians dancing around a pole ornamented with hanging strips of dog liver that they’re eating. The Indians labor in buckskins or simple coats. Little beadwork is displayed; there are few feathers and no war paint. With the exception of Death Whoop, calm is pervasive.

That painting first appeared in Mary Eastman’s The American Aboriginal Portfolio, published in 1853. It also appeared in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s six-volume Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Conditions and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, first published in 1851, for which Eastman provided 275 drawings and watercolors. Death Whoop shows an Indian scalping what appears to be a white settler. Mary Eastman describes the scene: “[The Indian’s] blood-stained knife he grasps in one hand while high in the other he holds the crimson and still warm scalp. … Right joyfully falls upon his ear the return of his death-whoop; it is the triumph for his victory, and the death-song for his foe.”

Responding to Native American concerns, the 1867 version of Death Whoop was removed from the committee room in 1987, returned in 1995, then removed again in 2007.

In the committee room, I ask Wivchar which of eight surviving Eastman paintings she prefers. She steps toward Feeding the Dead. “I really like this Indian burial. It’s a lovely landscape, the subject matter is a balance of quiet empathy, as well as a clear illustration of a cultural custom. It captures what seems to have been the point of this group of paintings.”

The canvas shows two Indians before a coffined figure lying on a raised platform. “It’s nicely balanced,” Wivchar says, “between showing the domestic or cultural activity and giving you a view of what this upper-Mississippi environment looked like. It shows the person putting food up on top of the burial scaffold … the soul took a certain number of days hanging around with the body after death. So you had to bring food to the grave every day. The painting’s nice and quiet. I think it probably gives a better idea of what Native American life might have been like than a buffalo hunt or a ceremonial dance.”

One is struck by the affection for Native Americans and their culture in these paintings. Eastman was soldierly reticent in his correspondence and remarks; one wonders if the subjects in his art weren’t the objects of his purest love. “I was looking at an obituary from his hometown newspaper in Maine,” Wivchar recalls, “and it was saying that as a youth, ‘He was remarkable for nothing more than his diffidence and adherence to rules.’ He had a military personality, it seemed. When you read his letters he’s always straightforward, not expressing any feelings.”

After completing the Committee on Indian Affairs assignment, Eastman took one final commission: to paint, for the House Committee on Military Affairs, images of 17 forts that had held prominence in settling the West or in winning the Civil War. “In those paintings,” Wivchar says, “the underlying message was supposed to be about union. The Civil War is over and here is the grand reach of the United States military. It goes from New Mexico to Maine. And from Fort Jefferson, off the Keys, to northern Minnesota.”

We viewed these oils, which hang in dark corridors beneath the Capitol Rotunda. Eastman’s forts are set in tranquil land or waterscapes, rendered with Hudson Valley School detail and a Rembrandt-ish light. One depicts a riverscape set on the barricades of West Point, cadets at ease. One cadet courting a sweetheart is particularly lovely. Eastman considered this his masterpiece. Despite the academy’s rigors, he’d been content there — first as a student, and later as an instructor of topographical drawing. In a separate hallway we viewed Eastman’s portrait of Fort Snelling, the scene of his finest watercolors and, living near the Sioux, arguably his greatest happiness. The fort hangs above the Mississippi, with its bankside teepees and prairie, like a wilderness Parthenon.

On August 31, 1875, in Washington, D.C., Eastman — long in failing health, and a painter who art critic Patricia Condon Johnston, over a century later would call, “Arguably the foremost pictorial historian of the American Indian” — collapsed at his easel and died.

- Seth Eastman, circa 1860s, United States Library of Congress

- Seth Eastman, “Rice Gatherers” | Oil on Canvas | 1867 | All works are from the collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

- Seth Eastman, “Dog Dance of the Dakotas” | Oil on Canvas | 1868 | All works are from the collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

- Seth Eastman, “Death Whoop” | Oil on Canvas | 1868 | All works are from the collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

- Seth Eastman, “Feeding the Dead” | Oil on Canvas | 1868 | All works are from the collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

No Comments