14 May Grounded in History

TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY TAOS, NEW MEXICO, hardly seemed the type of place to spark an art revolution.

It was a dusty, isolated, frontier outpost… in a territory that wasn’t even a state yet. Within just a few years, however, this sleepy old village metamorphosed into one of the greatest art towns in America. And Joseph Henry Sharp [1859–1953] and Eanger Irving Couse [1866–1936] helped make it happen. The pair of artists drove the concept of Southwestern art — and the town of Taos — into the American consciousness. Now, the 2.3-acre piece of land on which they performed this miracle is about to raise that consciousness once again.

The Couse-Sharp Historic Site, where the two artists once lived and created art for the ages, will unveil Sharp’s newly renovated studio this June. For devotees of Southwestern art — along with Taos as its wellspring — this will be an extraordinary addition and an intimate look inside a long-gone era.

The Couse-Sharp Historic Site now contains Couse’s home and studio, the garden cultivated by his wife, Virginia, the machine shop of his son, Kibbey, and Sharp’s two art studios. (Sharp’s original studio was an old chapel adjacent to his house, called La Luna, behind which he built a larger studio in 1915.)

The unveiling of Sharp’s renovated, larger studio will highlight a permanent interpretive exhibition dedicated to the artist, which includes significant artwork, correspondences, personal ephemera and Native American artifacts he collected, many of which appear in his paintings. In addition, it will shed more light on those halcyon days.

“The upcoming event is very meaningful for the local community, as well as for Southwestern art lovers all over America,” says Davison Koenig, executive director and curator of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site. “And we’re thrilled at the opportunity to add this meaningful piece of Taos history to the existing site.”

Sharp was the first artist of note to visit this sleepy village in 1893. He was instantly taken by the light, the colors and the mystical aura of the place, as well as the majesty of 12,305-foot Taos Mountain. He was captivated, as well, by the faces and culture of the Tiwa people, who inhabited the 1,000-year-old pueblo below the mountain. So much so that he came back for another look in the summer of 1897.

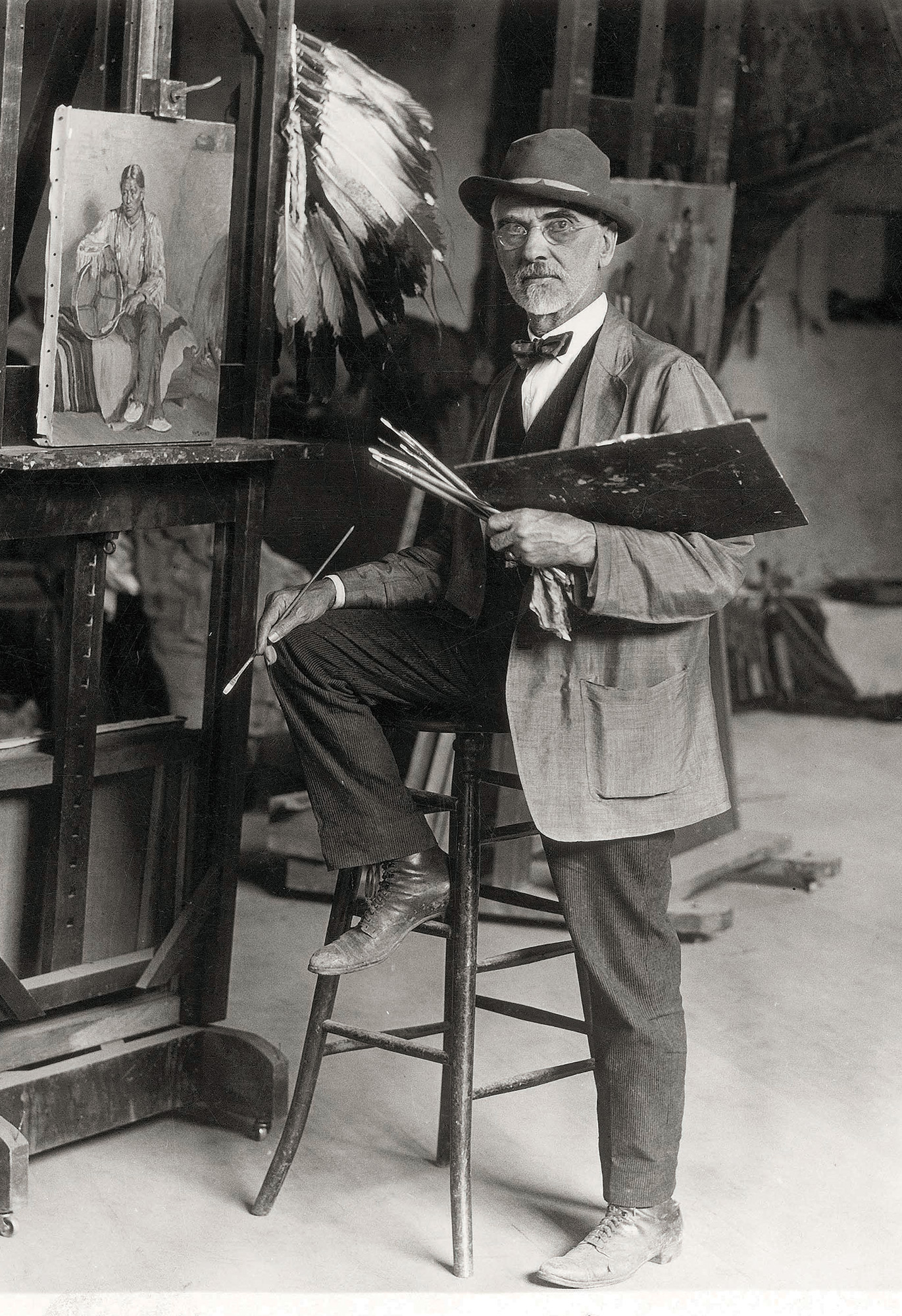

Sharp spent the summers in Taos, painting the faces and customs of the Tiwa, and winters in Montana at the Crow Agency. He bought an old adobe house, on what’s now the Couse-Sharp Historic Site, in 1908 and the adjacent chapel the following year, which he converted into a studio. In 1915 — the same year he helped found the Taos Society of Artists — he built the larger studio that’s just been renovated.

Sharp inspired other emerging artists to visit Taos, among them Ernest Blumenschein [1874–1960] and Bert Phillips [1868–1956]. In 1898, the two men arrived in a horse-drawn wagon that broke down just outside of town, so Blumenschein mounted one of the horses and rode into the nearest town, Taos, for help. His recollection of the experience as he rode through the New Mexico landscape reflects the impact the foreign land had upon him:

“No artist had ever recorded the New Mexico I was now seeing. No writer had ever written down the smell of this air or the feel of that morning’s sky. I was receiving … the first great unforgettable inspiration of my life.”

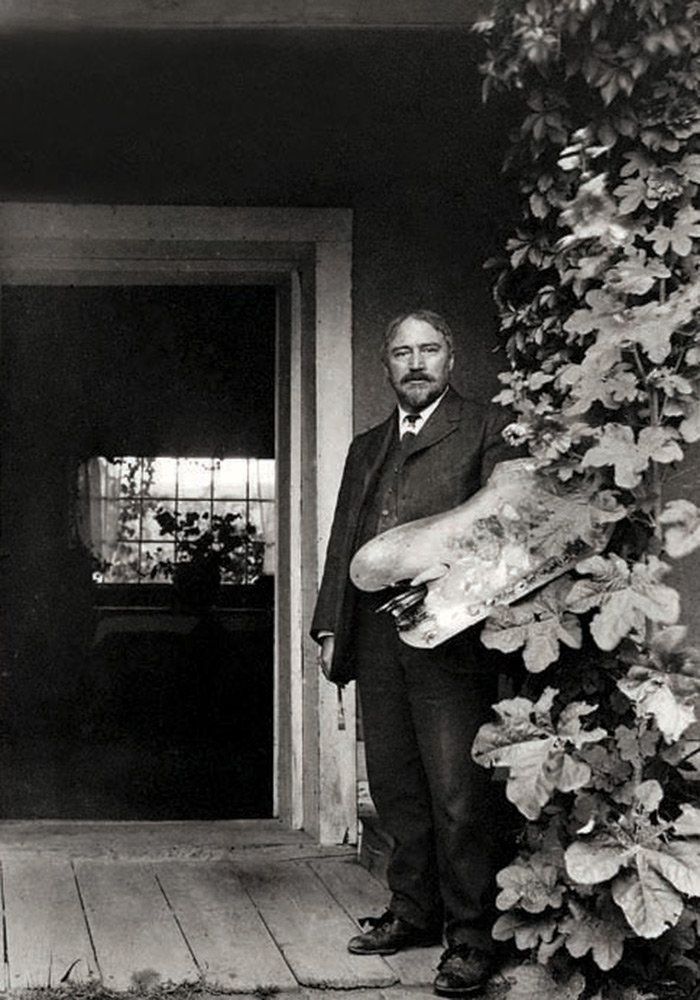

After seeing Taos, Blumenschein spoke with Couse on a New York street corner about the town’s unique light and spirituality and the availability of American Indian models. Couse came to see for himself in 1902, bringing his family. They took the “Chili Line” railway from Santa Fe halfway to Taos. When the tracks ended at Tres Piedras, they disembarked from the train and traveled the rest of the way in a stagecoach driven by a character named Long John Dunn.

The Couses’ first impressions were hardly glowing. They described Taos as appearing like a village from biblical times, with mud houses and women dressed in black.

However, after spending several summers here, Couse bought property in 1906, and three years later traded it for the property next to Sharp’s on Kit Carson Road.

“For many years, this small plot of land was one of the epicenters of the art world,” says Virginia Couse Leavitt, Couse’s granddaughter, who still spends summers in Taos. “The creative energy generated here — and the elevation of this art form into an exciting new genre — helped put the little town of Taos on the map.”

Couse had grown up in Michigan, near the Chippewa, and developed an interest in painting Native Americans at an early age. He studied art in Paris in the late 1880s, where he met his future wife, Virginia. His first painting of a Native American was shown at the Paris Salon of 1892.

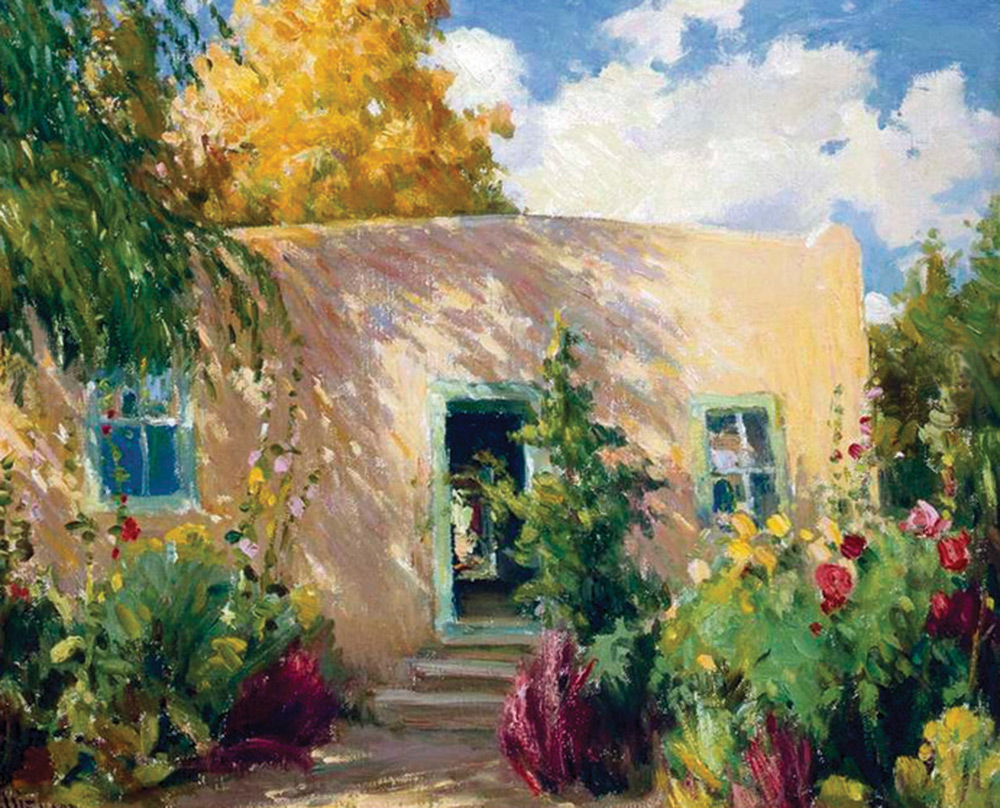

After Couse built his house and studio next to Sharp’s, the two artists developed a lifelong friendship and a lifetime of creativity fueled by this new genre they helped establish. During those years, Sharp created works such as The War Bonnet Maker, with a Native American artisan creating a headdress; Leaf Down, a picture of a woman sitting in a tepee with her shadow behind her and looking straight at the viewer; and Taos Fishing Trip, with a lone Native American subject casting a line into a river. Couse endowed us with gifts such as The Water Jug, of a Native American drinking by a stream, yellow aspens glowing behind him; Moonlight Spring, a quiet portrait of a Native American as nighttime envelops the mountains; and Couse’s House, of… Couse’s house!

After Sharp’s death in 1953, the site was managed by Virginia Couse Leavitt and her husband, Ernest, until 2001. That year, they helped establish the Couse Foundation to preserve this historic property for future generations.

“Sharp’s studios were never empty after he died,” says Laura Finlay Smith, curator of The Tia Collection in Santa Fe and a board member of the Couse Foundation. Smith managed The Tia Collection’s substantial contribution to the Sharp studio’s restoration and exhibition. “It was rented out to numerous artists all that time, who were lucky enough to be able to create their art in the footsteps — literally — of an immortal.”

Couse’s home and studio, on the other hand, were never changed, and have been diligently preserved to remain as they were during the artist’s lifetime.

“It’s a poignant place,” Koenig says. “He died suddenly in 1936, leaving unfinished paintings on his easels. And they’re still there.”

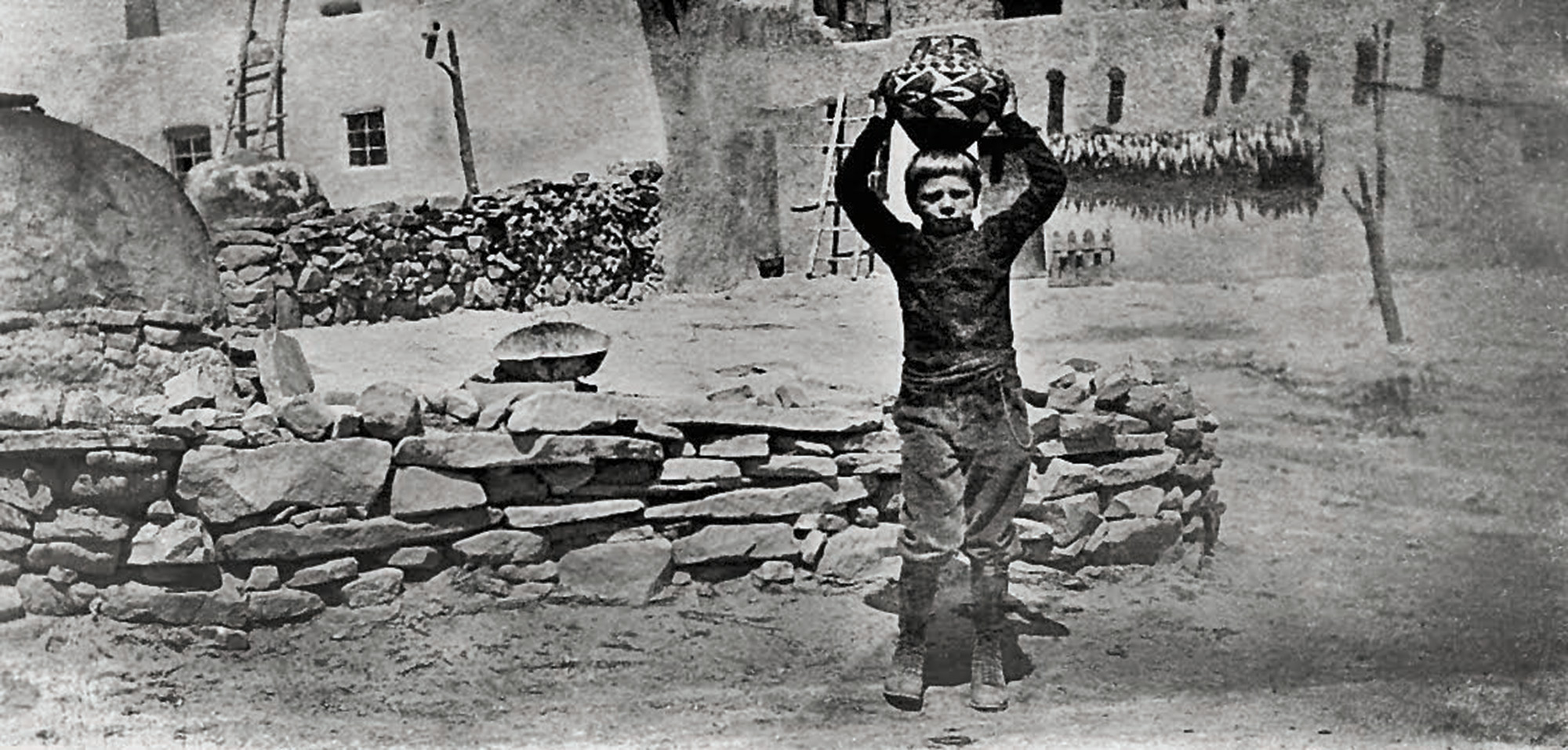

During this era, Taos was probably the least-likely place in America to generate a new art form. For example, Ralph Meyers, a well-known artist in his own right, used to hold court in the Plaza. Mounted on his white horse, he wore cowboy chaps, boots and a white 10-gallon hat, with a holster and six-shooter at his side. People walked by Meyers without a second glance because it wasn’t unusual. The Tiwa people would walk from the Taos Pueblo into town, wearing traditional garments and carrying their beautiful flutes, ceremonial items, jewelry and pottery to sell.

“By bringing back Joseph Sharp’s studio,” Smith says, “we’re adding a very important — and very necessary — piece to the bigger story of the arts in Taos and to this town’s role in the creation of an essentially American art form.”

- A study by Couse of the grounds, home and studio. (detail)

- Couse’s studio hasn’t been changed since his passing in 1936.

- Sharp at work at his easel. Photo courtesy of McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming

- Sharp and Eanger Irving Couse, at Couse’s home in the 1920s.

- Kibbey, Couse’s son, at Acoma Pueblo, circa 1910

- The welcoming entrance to the Couse property from Kit Carson Road in Taos, New Mexico.

- Couse in his studio.

- Joseph Henry Sharp, “Sharp’s Sitting Room” | Oil on Cavas | 16 x 20 inches | Gifted to Couse’s grandson in 1935 by Sharp

- Sharp’s first studio, circa 1912, built by the Spanish as a chapel in 1835.

- Sharp’s renovated studio, prior to the installation of the new exhibit.

No Comments