29 Dec The Lens of History

IN ITS INFANCY AS A FINE ART, PHOTOGRAPHY IS A MEDIUM that has fully emerged within the past 200 years. Consider that alongside a painting created with some 30,000 years of tradition and scholarship behind it. It’s no surprise then that photography has only recently been embraced and validated as collectible art.

The first serious auction of historic photographs in the art world took place in 1974. Ten years later, in a carefully orchestrated acquisition, the Getty Museum purchased 18 significant privately held photography collections. The bold move unleashed a wave of relevant books and articles, connoisseurs and dealers, while museum collections and the major auction houses have been working ever since to establish themselves in the new realm.

“The real turning point was when the Getty Museum quietly purchased about 50 percent of the greatest holdings of photography in the world. It’s like buying the entire history of a medium,” explains Peter Fetterman, owner of the Peter Fetterman Gallery in Santa Monica. Fetterman carries many of the mid-century modern photographic masters, and his finger is on the pulse of the museum and collecting world. “When the Getty made that major acquisition, the whole art world went ‘wow’ to the stuffy old museum, but the Getty knew what it was doing.”

With more than half the known heritage of the photographic world taken off the market in a single procurement, the floodgates for collecting historic photography were opened. Even so, says Fetterman, obtaining historic photographs is still relatively affordable. “Photography is the only medium where you can buy the same masterpiece that a museum has,” Fetterman says.

“Every major auction house now has their own photography expert,” says Thomas Minckler, who has been assembling objects relevant to the history of the American West since 1972. Working from Billings, Montana, and New York City, he is an authority on vintage photography as well as rare books, historic documents, 19th- and 20th-century painting. “Historic photography is still a bargain. Certainly there are genres of photographs that are going for half a million dollars at auction, but $15,000 for a rare historic photograph is considered very expensive,” he explains. Still, he emphasizes that “the demand is going up, which translates into value.”

Home on the Range

Many photographers made their way west as part of the homestead movement. A handful settled in and documented everyday life with an intimacy and informality that came with established personal relationships. Laton A. Huffman (1854-1931) initially arrived at Fort Keogh to become a post photographer and eventually moved to Miles City, Montana, to open a studio.

For 35 years he captured what he considered the last frontier of the American West — “a chapter forever closed.” He witnessed the disappearance of the great herds of buffalo and was well acquainted with the Northern Plains Indians. When the great cattle drives began to cross the vast, open ranges of Montana, he captured an extensive series on cowboy life as well as hunting, herding and untamed Western landscapes. Today, Huffman is commonly referred to as the Charlie Russell of photography.

“I carefully choose my images based on condition and subject matter. One of my favorite L.A. Huffmans is a photograph of Conrad Kohrs at his ranch outside of Deer Lodge. It was the first major cattle ranch in Montana,” Minckler notes, stressing the fact that such historic significance and relevance are essential when he collects photography.

Minckler purchased the entirety of the original L.A. Huffman studio collection, a compilation of extraordinary significance consisting of more than 3,000 photographs, documents and a variety of artifacts belonging to the frontier photographer. In his care, the original photographic prints were cataloged and manuscript correspondence carefully transcribed, and through a recent purchase-donation agreement, they are now held in the McCracken Research Library of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Wyoming.

Cowboys and Western ranch life were also primary subjects for Texas photographer Erwin E. Smith (1886-1947). Smith always wanted to be a cowboy and artist. He studied sculpture and painting in Chicago and Boston before returning to Texas ranching and eventually chose photography as a way to record the authentic life of a range cowboy. The endeavor took him throughout Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, and his images are some of the most recognized in the genre. “Erwin was part of the ‘Montana’ tradition. He corresponded regularly with Huffman,” explains Andrew Smith, a seasoned collector, publisher and dealer in Santa Fe. “His work is an extremely rare find today.”

The Native American World

In the beginning, photographs were regarded as scientific documents rather than art. Some photographers straddled the worlds of science and art, many worked strictly in a documentary style and some romanticized the concept of what was believed to be “The Vanishing Race.”

“One of my favorites is Ben Wittick,” says Mark Sublette, owner of the Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson. “He came out West to become a photographer and documented a lot of the early images of Native American life. His first photographs were taken as early as the 1870s. He concentrated on documenting people rather than getting a pretty picture. All of his images are very real,” Sublette explains.

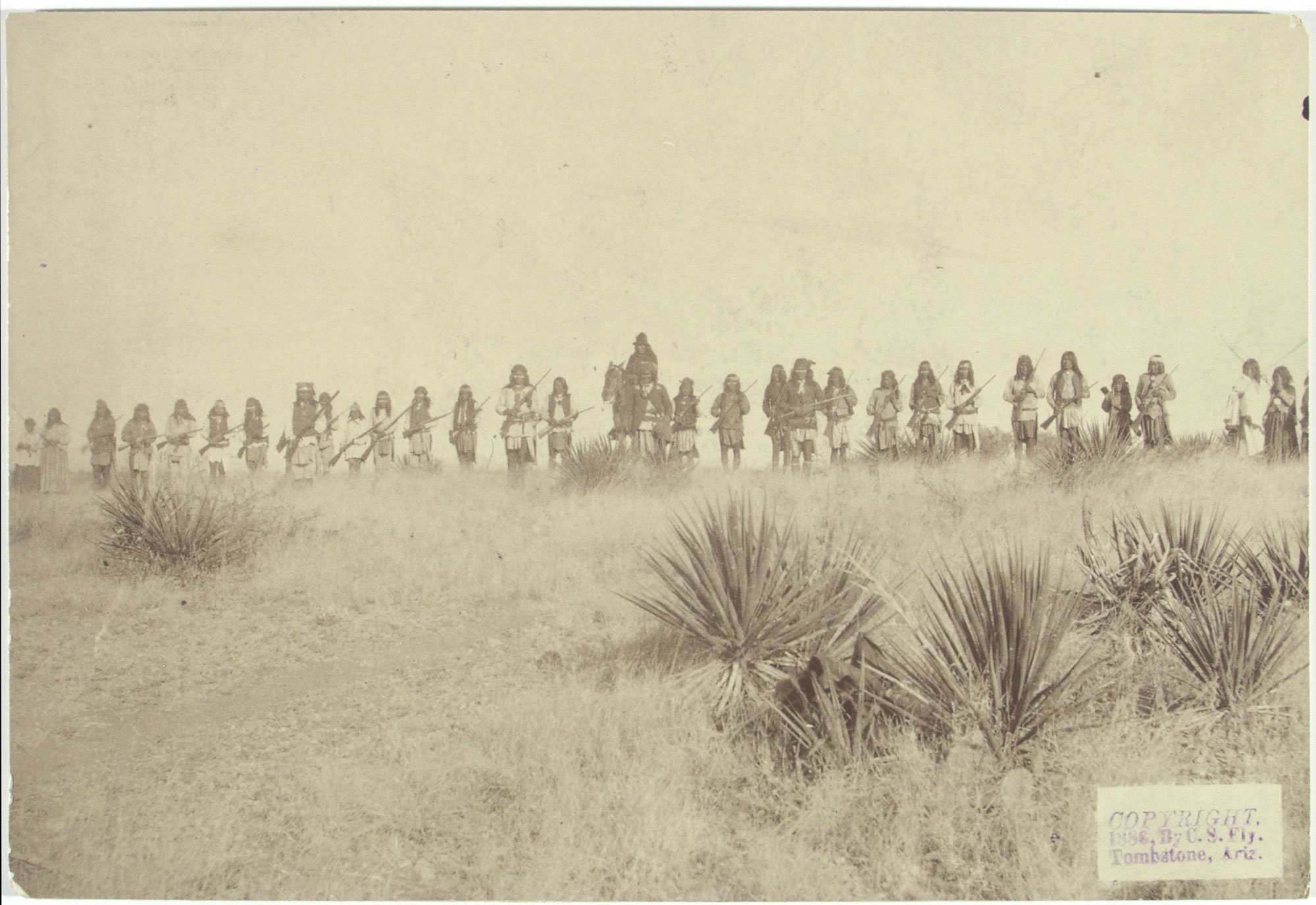

Historic photography was pretty much a regional endeavor and modern collecting seems to be following the same route. “We don’t have a lot of Huffmans coming through the door, but we get really excited when we see a C.S. Fly. He’s our Huffman,” says Sublette. Camillus Sidney Fly had a studio in Tombstone, Arizona, and was most famous for photographing the local characters, the Apache tribe and Geronimo’s surrender.

“I have a whole collection of Geronimos. He was photographed often by at least a half-dozen well-known photographers. People would seek him out when he was a POW and after with the Wild West show, and he charged them. He was an interesting subject. People remember.”

A favorite and relatively undiscovered Southwest desert photographer is William M. Pennington (1874-1940). Pennington worked from the turn of the century into the 1920s and produced a prolific number of prints from his studio in Durango, Colorado, mostly of the Navajos and Mesa Verde. “From a dealer standpoint, I can still find his images out there. I have to take into consideration that there is a body of work. It’s still affordable. You can get an original print for around $1,200,” offers Sublette.

Sublette personally collects photography by image, rather than artist. “There’s an innate sensibility you get from certain images. Those images call to people, and it develops scarcity and value because everybody’s drawn to it. There has to be a strong visual connection. Some of the work I have is totally anonymous. I don’t know who the artist was and my choices are completely image-driven. You really have to go with your gut — especially if it’s with a lesser-known artist.” Use visual sensibility, he suggests, and find the photograph in as good condition as possible.

When asked about a checklist for collectors, he includes Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) as a staple. “Nobody else spent so many years of their life covering one subject. He was seminal to Western art,” Sublette says.

There is no question that Curtis remains sought after for his mastery of orotones and platinum prints, his commitment to his project, The North American Indian and his prolific body of work. The value of his original prints and photogravures continue to escalate. In October of 2007, the top lot at Swann Galleries’ auction of “Important 19th- and 20th-Century Photographs” was a partial set of Edward S. Curtis’ magnum opus, The North American Indian, with 16 complete portfolios containing his large-format photogravures and 16 fully illustrated text volumes in handsome morocco bindings. The set, number 74 in an edition of 500, signed by Curtis, his financial backer J.P. Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt, sold for $1,008,000.

Exploration, Railroads and National Parks

The West before the turn of the 20th century was full of characters in an expanse of undiscovered frontier. Photographers came out West in wagons and trains outfitted with hundreds of pounds of glass plates and chemistry. They set up shop in frontier towns, or created traveling studios out of wagons or train cars. Photography became a vehicle for mapping the contours and characters of the West, documenting a vibrant and dynamic real-time history.

Hired by the government to capture landscape images of areas that were being surveyed, many photographers came out West burdened with equipment and ready to document architectural views of cities, settlements and capture the geological wonders of the landscape. Usually a part of organized expeditions, they worked as an extension of illustrators and painters who preceded them.

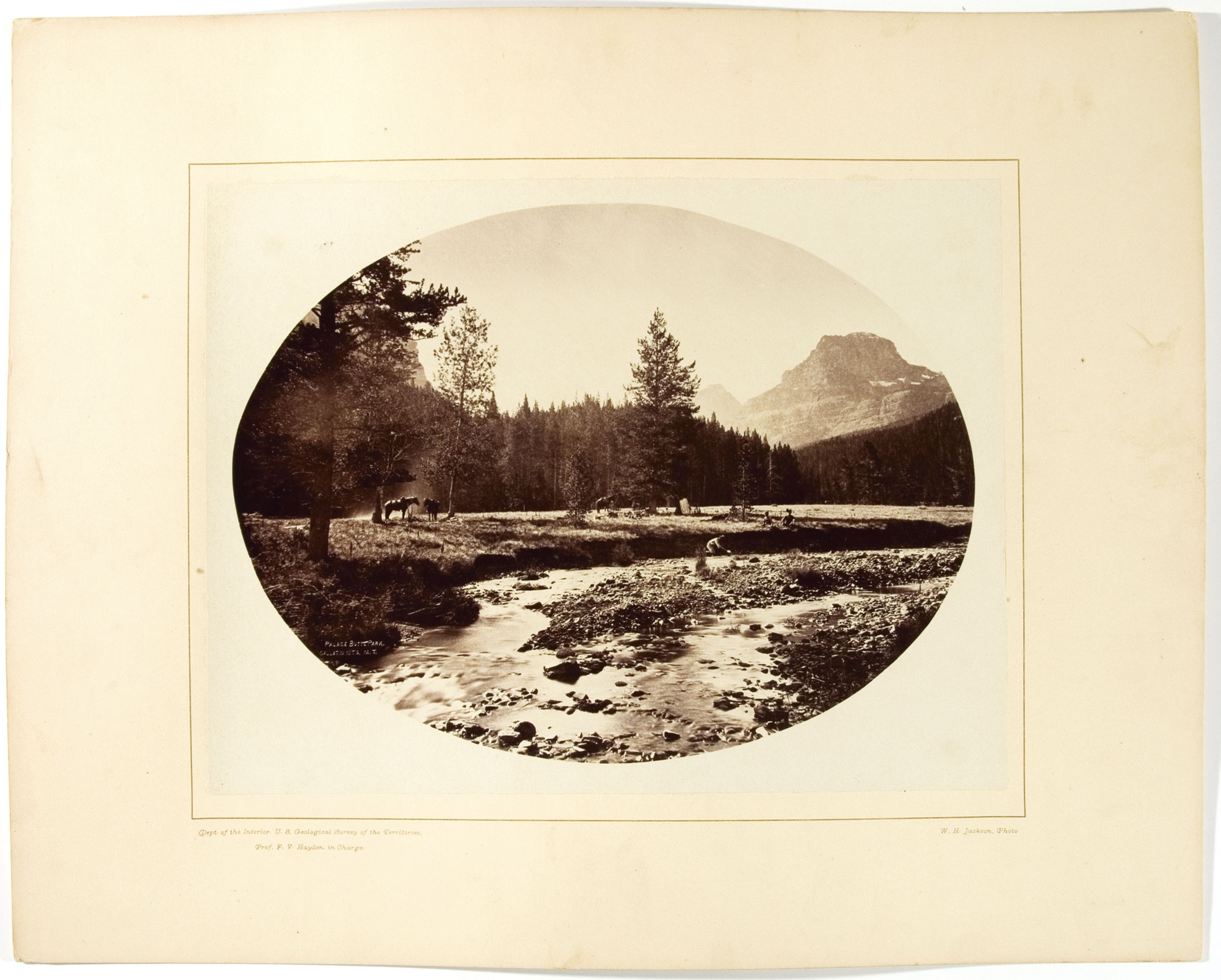

One of the most notable of this genre is William Henry Jackson (1843-1942), known widely as America’s pioneer photographer. He is most famous for his dramatic landscapes ranging from small albumen prints to enormous multi-mammoth plate panoramas more than 6 feet wide. “Jackson took extraordinary photographs, both early in his career and after he left Oklahoma and went on to Montana and Wyoming. A lot of his great work was done in Yellowstone National Park when he came out with the Hayden Expedition,” says Andrew Smith. “He made a collaborative album using other people’s negatives, as well as his own of mostly Native American portraits, that is the most rare and important in existence today. There are only 11 in the world and valued at about $3 million dollars,” Smith says.

Smith’s conversational pace accelerates as his enthusiasm and knowledge overflows with a lengthy string of facts, figures, names and anecdotes. “Those albums were the first grand project in America, well before Curtis’ The North American Indian. Jackson also published large-format landscape albums of Yellowstone in 10- x 13-inch format, and the worth is about one-quarter-million to one-half-million dollars for the 38 photos,” he says.

Smith’s career and interest in photography has spanned more than 30 years. “I’ve always liked photographs and working with book dealers. That’s when I first started seeing great photography,” he reflects. In 1980, he published his own first catalogue of Western exploration and historical photography. Since then he has pursued that interest as a specialty and has become a leading and respected aficionado in the field.

One of Smith’s recent publishing projects is that of photographer Adam Clark Vroman (1856-1914) who is considered to be one of America’s first modern photographers. He participated in three scientific expeditions in the desert Southwest and often traveled there on personal adventures. Vroman created elaborate, bound photo albums and sets that he gifted as keepsakes to his friends and colleagues, but didn’t participate in the photographic salons and exhibitions of his day. He passionately made his photographs for personal pleasure and in the interest of science.

Vroman’s foremost contribution to photography was his ability to exploit the wide range of tones inherent in platinum prints in the first visual vocabulary using a straightforward approach and dramatic capture of shadow and cloud. The influence of his use of tonality to create rich, sculptural values and his direct, precise and sensitive style can be seen years later in the modernist landscapes of Edward Weston, Ansel Adams and Paul Strand. “Vroman, Jackson and Timothy O’Sullivan all had a trained and intuitive sense of what makes a great photograph. They were conscious of where they put the camera and how they framed an image,” Smith says. “They looked at a negative as if it was a canvas.”

One hundred years of infancy in the Old West, the art of photography has endowed a legacy of images in a spectacular range of subject, shape and size. Through the lenses of all the historic photographers, both anonymous and known, this chapter of the wild frontier will never fully be closed.

Where to start

Andrew Smith Gallery | Santa Fe, New Mexico | 505.984.1234 | www.andrewsmithgallery.com

Minckler Fine Art | Billings, Montana and New York City, New York | 212.777.9255 or 406.245.2969 | www.mincklerfineart.com

Peter Fetterman Gallery | Santa Monica, California | 310.453.6463 | www.peterfetterman.com

Medicine Man Gallery | Tucson, Arizona | 800.422.9382 | www.medicinemangallery.com

The Thomas Nygard Gallery | Bozeman, Montana | 406.586.3636 | www.nygardgallery.com

Etherton Gallery | Tucson, Arizona | 520.624.7370 | www.ethertongallery.com

Vintage Versus Modern Prints

When purchasing photography, it is imperative to understand the difference between a vintage and modern print. The definition of “vintage” is not set in stone, but there is usually an accepted window of time that the photographer should have printed from the original negative — this varies up to 10 years from the original negative date. The price for a vintage photograph can be as much as six times the price of a modern print, when available. A rule of thumb is that all photographs made during an artist’s life are considered vintage or “early prints” and collectible. Most dealers and specialists recommend avoiding photos issued after a photographer dies. Such portfolios have little secondary market value.

Photographic Media…

The relationship between technology and aesthetics is integral to the history of photography. Here are the most common photographic media found in the world of collecting historic photography:

The Daguerreotype

One of the earliest forms of photographic printing (1839), the Daguerreotype is a direct process whereby the image is created without the use of a traditional negative. These photographs had little capacity for duplication, long exposures of three to 15 minutes posed challenges and the Daguerreotype was quickly replaced by the ambrotype, a faster and less expensive process.

The Albumen Print

Invented in 1850, the albumen print was the first commercially reproducible method of developing a photographic negative on a paper base. Using egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals, the image emerges as a result of the exposure to light without the necessity of a developing solution.

The Photogravure

Photogravure is an intaglio printmaking process initially developed in the 1830s to provide a permanent way of reproducing a photograph. The speed and convenience of silver-gelatin photography eventually displaced photogravure after the Edward S. Curtis portfolios of photogravures in the 1920s.

The Orotone Photograph

Often referred to as a “gold tone,” the orotone photograph is an image printed on a glass plate with a silver gelatin emulsion coating. The rear surface of the glass plate is then painted with banana oil impregnated with gold pigment to yield a toned image.

The Silver Gelatin Photograph

Since the archival technique was introduced in 1871, silver gelatin photographs have been a popular medium chosen to reproduce photographic images because of the relative ease of reproduction, lower cost and stability of the final image. The final image consists of metallic silver embedded in the gelatin coating and is still a revered way of reproducing photographs today.

The Platinum and Palladium Photograph

The platinum or palladium print is also referred to as a platinotype. When the process was invented in 1873, platinum was relatively cheap, but by 1907 the noble metal had become 52 times more expensive than silver. Platinum and palladium metals are among the most archival available and are more resistant to light, oxidation and chemical contamination than silver or gold. Platinum prints are among the most permanent objects invented by human beings. Incredibly, a platinum image, when properly made, can last thousands of years and outlive the substrate it is printed upon.

- Edward Curtis, “Watching The Dancers” | 1906 Photogravure | 15.25 x 11.25 inches

- L.A. Huffman, “Round-up Outfit Breaking Camp” | Negative Date: Ca. 1886 | Print Out Paper; 9 x 11 inches

- Camillus Fly, “Geronimo And His Warriors” | No. 178; Negative Date: 1886; Albumen; 7.1 x 9.5 inches

- William Henry Jackson, “Camp On Mystic Lake” | Negative Date: Ca. 1871-73 | Albumen 10.25 x 13.125 inches

- William Henry Jackson, “Palace Butte Park” | Gallatin Mountains, Montana Territory | Negative Date: 1872 | Albumen 9.25 x 12.25 inches

- Edward Curtis, “Geronimo – Apache, 1907” | Negative Date 1907, Photogravure 15.4 x 10.5 inches

No Comments