14 Sep Beyond Cowboys

THERE IS A STORY, PERHAPS APOCRYPHAL, that once upon a time the late and legendary American painter Andrew Wyeth was standing next to a bystander who, in turn, had been attracted to Wyeth’s portrayal of an old, white Brandywine River Valley farmhouse.

The work hung on the wall in front of them. Without knowing it was Wyeth himself nearby, the observer naively said, “This guy Wyeth, he sure is a fine house painter. But I wonder if he knows how to use more than one color?”

Amused, not insulted, by the remark, Wyeth reportedly shook his head affirmatively and replied, “Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?”

Had the viewer stepped closer, he might have noticed the convergent labyrinth of brilliantly executed abstract brushstrokes, laid down in a broad palette range of harmonized color tones — none of it being an actual shade of white — to achieve an extraordinary visual illusion, manifested as a farmhouse.

Over the course of art history, perceptions of many great artists have been framed by viewers’ literal interpretations of their subject matter. So, too, is it sometimes the grossly misleading case with American realist Bill Anton, held up among the finest living painters of modern cowboys in the American West, but who has little desire to be known as a “cowboy painter.”

This autumn, Anton’s Western scenes of figures and landscapes, are featured in an eight-artist exhibition at the Woolaroc Museum outside of Bartlesville, Oklahoma. The Woolaroc’s Best of the Best Retrospective showcases paintings by Anton, George Carlson, Len Chmiel, T. Allen Lawson, Dean Mitchell and Andrew Peters, as well as sculptures by Steve Kestrel and Tim Cherry.

Opening in early October and running until the end of 2017, this assemblage is the third time in six years that the Woolaroc has staged an artistic happening attracting national and international notice.

“We want to foster a broader appreciation of Western art, to show it’s more than what it implies. To do that, we are bringing together a truly phenomenal group of acclaimed individuals who have each taken it in their own direction,” says Robert Fraser, the Woolaroc’s CEO.

The mastery displayed in the retrospective pieces (made available by private and public collectors) and the anticipation surrounding fresh works they will unveil for sale has created a buzz, Fraser notes.

Indeed, it would be significant to have any one of these artists doing a show on their own. Maybe more than anyone else in the lineup, Anton represents an extension of the talent arc reflected in the Woolaroc’s own permanent historic collection. Owed to acquisitions made a century ago by legendary oilman Frank Phillips, who founded Phillips Petroleum in 1917 and then established Woolaroc Ranch, the world-class trove started with Phillips and his wife, Jane, filling the walls of their home and lodge with art by some of the greatest Western painters of the day.

Many the Phillipses knew personally. They would invite them and other international notables to attend annual ranch soirees, the spirit of which has been revived in the Woolaroc’s new ambitious exhibitions and its wonderfully renovated gallery spaces.

Critics say Anton evokes the same kind of impact celebrated in the works of three of his own heroes — Frank Tenney Johnson, Edgar Payne and Maynard Dixon.

Born in 1957, Anton was raised in Oak Park, Illinois, the same Chicago suburb where Frank Lloyd Wright and Ernest Hemingway lived. Like Hemingway, Anton felt compelled to leave the Midwest. He saw mountains for the first time when his family took a vacation to Glacier National Park in northern Montana, and he was instantly smitten with the grandeur of earth pushing into the sky. By the time he reached his 19th birthday, he had entered Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff not far from the North Rim of the Grand Canyon.

“It was the geography, not the culture, that drew me out of the flatlands initially, particularly the Rockies,” he says. “Out West smelled like perfume, not diesel. Then, I discovered a regional art form thriving there. I had only known the subject of ‘Western art’ from Marlboro magazine ads I had been copying in pencil and pastel. When I found out there were still working ranches, I made it my business to sketch the scenes that were happening there, and along the way I taught myself to ride and rope a little.”

While studying art in college, Anton was dissuaded, as so many of his generation were, by teachers who dismissed realistic representation. Still, he resisted the guidance, attracted to classical approaches to figure drawing and painting. “I knew instinctively that civilization was not built on subjective pseudo-intellectual dreck but on hard work that harkened back to the past. It was obvious to me that the current art trends were bankrupt, no matter what the museum elites said,” he explains.

But bucking them is easier said than done. Fortunately, Anton already heeded earlier sage advice telling him to leave his camera at home when gathering reference, to get a good outdoor easel and paint the West on location. “I scraped up a couple hundred bucks and did it,” he says, noting a paradox. “The difficulty of working from life was intimidating and therefore so essential to growth that even a novice like me could see its value.”

Later, with the encouragement of his wife, Peggy, he began selling pencil drawings and trying to support his young family on a meager art income. He made hundreds of field studies, too, but he deemed few of them worthy enough for public circulation. Tenaciously, he stayed with it until plein air became his favored working method. “The unexpected benefit,” he says, “was that the arsenal of problem-solving skills demanded by being outside helped enormously back in the studio.”

Since the late 1980s and early 1990s, Ned Jacob, the noted draftsman and adherent of plein air who had been mentoring Anton and a talented group of others, told me to keep an eye on Anton for he was in the middle of a profound transition. Jacob was prescient in his certainty that great things would come from the artist.

Anton acknowledges being an exponent of the 10,000 hours of training premise, that this is how long it takes before one can work confidently on pure instinct without impulse to render. He credits his plein air work with teaching his mind’s eye to recognize the spontaneous elemental energy flowing through a scene. A born-again Christian, he says his life has been divinely directed, but his quest to get at the truth of his subject is an ongoing mortal struggle for which there are no shortcuts.

Besides Jacob’s influence, a breakthrough happened when Anton worked with the impressionistic landscape painter Michael Lynch. “I was bemoaning the fact that my figures did not appear to be integrated enough into the landscape. I was, at the time, painting background to foreground, figure last,” Anton explains. “He took a brush and painted one of my figures simultaneously with the background, putting in and refining the figure via the sky and mountains. My response was: ‘Wham! Instantly harmonious integration. Figure and nature seamlessly imbued with ambient color and light.’ I never worked a painting my old way again.”

Jacob and Lynch led by example, not preaching, just like James Reynolds, another Anton mentor, did. “I always liked their reductive wisdom, ‘If you think your painting needs something more, take something out.’”

Dan Corazzi, a landscape and wildlife photographer, is a board member of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. He and his wife, Maryann, are collectors of Anton’s work, having begun with giclées and slowly added originals as budget afforded. They have visited Bill and Peggy Anton at their place outside of Prescott, Arizona.

For an artist at the top of his game, Corazzi says it’s noteworthy that Anton evinces no airs. “He is as genuine a person as you would ever meet. He is telling you exactly what he is feeling and that honesty and sincerity comes through in the art he creates.”

Anton has little regard for abstract expressionists and experimental artists who speak gallantly of non-representation but who can’t draw. With Lynch, Jacob and Reynolds, fundamentals were stressed “over the fluff and the hubris of ‘self-expression’,” Anton says. “Though the wasteland of abstract expressionism was in full throttle, Jim, Ned and Mike weren’t buying it. They were and are self-critical. No nonsense. Opinionated. When I wanted to know something, they told me in no uncertain terms, politically incorrectly, often harshly, and I loved them for it.”

The words of their philosophy were insightful, he points out, but more revealing is that they were applied. “Most of what I learned was attitudinal; how one should think about painting and who the right heroes were and ought to be,” he says. In a work such as Enough Already, featured in the Woolaroc exhibition, Anton’s own vivacious visual attitude shines, for it exudes a freshness and, as with Wyeth’s “house painting,” this portrayal of a cowboy on horseback is all about light, color, value, atmosphere, texture, draftsmanship, design and action forming a powerful confluence.

“Sometimes I like the idea of painting something for the sheer joy of laying paint without any thought to ‘story’,” he says. “I do that a lot. But Western art is steeped in story. I’m okay with that, too. I do think story paintings can be compelling. I also think they can be used to cover up one’s inadequacies as an artist. A painting should be able to stand alone without the aid of a narrative. But if you’ve got the goods, a narrative doesn’t hurt a bit and often enhances the viewer’s experience.”

George Carlson says he admires Anton for his technical ability, but more than that for daringly taking on a genre for which he attaches romance but refuses to drench it with cheap sentimentality. He points out the architectural aspects of Anton’s skies.

“Skies are simply an opportunity to emote and set a mood as is the case with light. I can’t design a horse or a human. But I can make a cloud any shape and size I want. They are vehicles for calligraphic, gestural power and wonderful compositional aids,” Anton says. “For me, the dome of the sky influences everything else in the painting, casting nuance or bombast, whatever you want. All that aside, the skies of the West and what lies beneath them just turn me on.”

Over the last decade, Anton has been one of the most decorated painters in Western art. In 2016, he was given the Frederic Remington Award at the Prix de West Invitational for his soothing low-key nocturne, Deep in the Wind Rivers, a piece that will also be featured in the Woolaroc exhibition. Early in 2017, at the Autry Center’s Masters of the American West, Anton took home the Spirit of the West Award for the predicament scene, A Fresh Grizzly Track. And numerous other awards preceded those.

More gratifying, he has earned the hard-won respect of peers counted among the finest painters in America. T. Allen Lawson, who in 2017 was awarded the highest honor in Western art, the Prix de West Purchase Award from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, says he has a masterful way of communicating light.

“I think Bill Anton is at the very top of painting Western genre subjects, but what most people don’t know is that he’s one of the very best plein air painters I’m aware of,” Lawson says. “His on-the-spot pieces are incredible and that sense of immediacy translates into his studio work.”

Lawson, who grew up in Sheridan, Wyoming, knows real cowboy culture from the make-believe kind. Anton, he explains, is a serious tactician who emanates no affectations. “He’s a cowboy painter because he’s a cowboy at heart, not one of these guys who just dresses up to play the part,” Lawson says. “In fact, when you see him at a show, he’s not trying to dress up as a ‘cowboy artist’ with a big hat. If anything, he’ll dress down by showing up in a sports jacket. I admire his professionalism, his thoughtfulness, the respect he holds for trying to make art that says something. But, at the same time, he has a real connection to the cowboy life. He understands the horse and unless anyone has tried to paint a horse, they probably don’t know how damned difficult it is. He can paint a horse from any angle or motion, in any light, and his command of it shows.”

Lawson, who knew Wyeth and who earned his admiration as a like-minded Realist, believes that if Anton wanted, he could probably paint white houses and red barns, too. Those who take the subject matter literally would be missing the point, that it isn’t about the replication of an object; the magic happens in the illusion and the certainty that never really understanding the power of the trick is what feeds the eternal mystery of fine art and fills the soul.

Anton may not have been born in the West, but he is one of her greatest admirers. For him, it is not about loving one thing, it is about savoring the wonder that engulfs it all.

- “A Fresh Grizzly Track” (detail) | Oil on Linen | 36 x 48 inches | 2017

- “Deep in the Wind Rivers” (detail) | Oil on Linen | 36 x 42 inches | 2016

- “Wyoming Conference Call” (detail) | Oil on Linen | 32 x 50 inches | 2015

- “No Place to be Shoeless” | Oil on Linen | 34 x 32 inches | 2015

- “Enough Already” | Oil on Linen | 16 x 16 inches | 2012

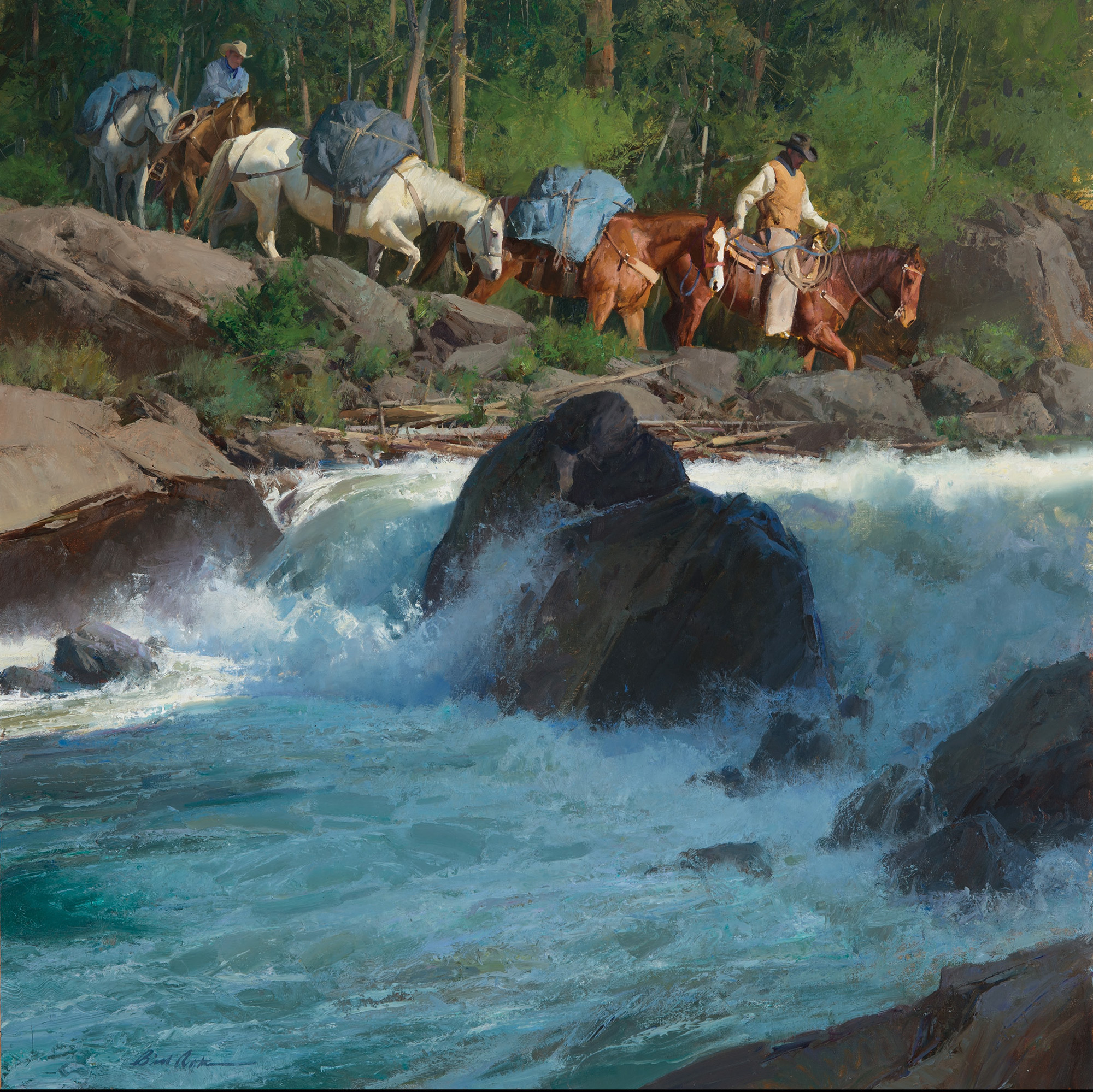

- “The Search for a Crossing” | Oil on Linen | 50 x 50 inches | 2016

- “Storm on the Dallas Divide” | Oil on Linen | 8 x 10 inches | 2016

No Comments