15 Mar Perspective: The Gentle Rebel: Olive Rush [1873–1966]

It seems that Olive Rush [1873–1966], a pioneering artist long hidden in the shadows of American art history, may have contributed to her own obscurity by accidentally branding herself as a mild Quaker spinster, rather than the worldly, independent, adventurous spirit she was. After having a professional photograph taken in New York City, circa 1918, in her grandmother’s Quaker bonnet and dress, Rush used the photo for publicity for many years, allowing it to be reproduced for newspaper and magazine articles. “Olive has been overlooked, seriously forgotten, ignored by scholars,” says art historian, author and artist Jann Haynes Gilmore, who sees the fateful photo as a significant factor in the painter’s decades-long neglect.

Olive Rush (left), Sarah Katharine Smith (center) and Ethel Pennewill Brown (right) on the steps of the Howard Pyle Studio, ca. 1905–10

That status has begun changing, thanks in part to Gilmore’s award-winning biography, Olive Rush: Finding Her Place in the Santa Fe Art Colony, published in 2016 by the Museum of New Mexico Press. Rush was also included in the 2017 PBS documentary, “Painting Santa Fe,” and her works on paper were featured in a 2017 exhibition in Santa Fe, presented by the Historic Santa Fe Foundation and the Santa Fe Quaker Meeting, and curated by art conservator and Quaker, Bettina Raphael.

Rush was a lifelong Quaker, deeply and absolutely. But she was far from the deferring stereotype her publicity photo seemed to suggest. Academically trained in art and well traveled, she became a nationally known magazine and book illustrator, portraitist, muralist and award-winning painter whose work was included in exhibitions around the country. Her social reform and anti-war convictions were aligned with both Quaker tenets and the emerging early 20th-century movement of educated, independent-thinking women: She was an early environmentalist and a passionate believer in arts education. Her Quaker anti-war sentiment was expressed in some of her paintings during World War II, and she took part in clothing drives for war refugees.

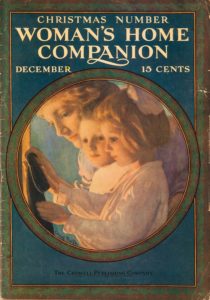

Olive Rush’s cover design for “Woman’s Home Companion,” December 1909; All images from “Olive Rush: Finding Her Place in the Santa Fe Art Colony” by Jann Haynes Gilmore, courtesy of Museum of New Mexico Press.

At the same time, the inward-looking spiritual foundation that began for Rush on an Indiana farm was reflected in much of her art during her long life and prolific career. Her paintings, particularly in watercolor, are often described as delicate, lyrical and ethereal, and frequently feature lovely, vulnerable animals such as deer. Her illustration work and portraiture include heartwarming images of mothers and children. After settling in Santa Fe in 1920, she rendered Native American subjects in ceremonial or domestic settings. “There was a sense of gentleness about her,” says Raphael. “But she was a gentle rebel.”

That gentleness, along with open-mindedness, reverence for life and a strong interest in beauty and art, was nurtured and encouraged by her parents, Nixon and Louisa Rush. Olive was the fourth of six children (a seventh died young) and attended a Quaker academy established by her parents on their farm, where she loved to sketch the animals and scenery. At 16, she enrolled in Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. There, one of her professors recognized her talent and encouraged her to attend art school and to show her art widely.

Rush chose the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., and while the Corcoran’s classical training gave her a strong foundation in artistic skills not often extended to females in the late 1800s, the young artist found its rigid structure confining. Throughout her career, Rush experimented with styles, mediums and subject matter, intent on forging her own path with originality and imagination. “She emphasized the importance of artists being free to follow their instincts,” Raphael says.

Following the advice of a Corcoran professor, in 1893 Rush headed for New York City and the Art Students League. She arranged her classes to be able to spend part of each day working in illustration to earn money, first at Harper’s Publishing House and then as a freelance illustrator. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, she gained national acclaim for her illustrations for books and for women’s and popular magazines, including three Christmas covers for Woman’s Home Companion.

“Girl on Turquoise Horse” | Oil | 1921

In a gesture that recognized Rush’s talent as an illustrator, renowned illustrator Howard Pyle invited her to study with him. Pyle’s Wilmington, Delaware, school was aimed at mature, professional illustrators to whom he offered critique and guidance and helped establish contacts in the publishing world. Rush had a studio there for a few years, during which time she also pursued easel painting and wall decoration. At Pyle’s school she developed a lifelong friendship with fellow artist Ethel Pennewill Brown (later Ethel Leach). For more than 50 years, the two friends wrote to each other virtually every month. Their letters, now owned by Gilmore, are a treasure trove of material that became the foundation of the artist’s biography.

Olive Rush painting the murals in the Santa Fe Public Library, Santa Fe, New Mexico, ca. 1934–35

Between 1911 and 1913, Rush traveled in Europe with an artist friend, studied in Paris, and then studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. By the time she first visited Arizona and New Mexico in 1914, traveling by train with her sister, Myra, and their widowed father, she was ready to leave the commercial world of illustration for art that engaged her on a deeper and more personal level. That two-month excursion, whose highlight for Rush was Santa Fe, marked a turning point in her life.

Fireplace decoration at El Mirador, near Alcalde, New Mexico, 1934

Soon after arriving in Santa Fe, Rush was offered a solo exhibition at the Palace of the Governors. It was well received, earning praise from local critics and serving as a prelude to her active role in the Santa Fe Art Colony. Returning and settling in Santa Fe in 1920, she found the city alive with people of like mind: artists, writers and cultural preservationists. For Rush, the New Mexico landscape and spirituality of Hispanic and Native American cultures were both an exhilaration and a balm. She traveled around the Southwest with artist friends, sketching and painting. With a modest inheritance, she purchased an old adobe farmhouse on Canyon Road, which later became the heart of the Santa Fe art scene. On Canyon Road, Rush became the “gatekeeper” for artistic minded visitors to Santa Fe. “She was lucky in where she settled,” Gilmore says. “She knew everything going on.” Among her visitors was President Herbert Hoover’s wife, Lou Henry, who purchased the 1921 painting, Girl on Turquoise Horse. Among Rush’s close friends were virtually all the artists and writers whose names are synonymous with Santa Fe during that era.

“Young Deer,” Watercolor on Paper, 14.75 x 21 inches, ca. 1940

Almost as soon as she bought her house, Rush began using its walls to experiment with mural painting in fresco — applying pigment directly on fresh, wet plaster. “She said she came to New Mexico to paint on pink adobe walls,” Gilmore says.

“Portrait of Indian Family,” Oil on Canvas Board, 12 x 18 inches, ca. 1914

In 1929, acclaimed New Mexico architect John Gaw Meem asked Rush to create murals on the walls of the dining room at La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe, which led to a request for murals at the Santa Fe Indian School. Rush demurred, but said she would teach the school’s best students to paint them. Not only did the students learn mural wall painting, but Rush showed them how to paint murals on canvas that could be rolled up and shipped. The students, many of whom went on to become nationally known artists, had their paintings sent to New York City, Washington, D.C. and the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago. It was the start of Rush’s sustained and significant advocacy for Native American arts, which she continued throughout her life. Years later, she hired a number of these artists, including Pablita Velarde, Pop Chalee, Harrison Begay and Awa Tsireh, to help her paint murals on the exterior of the John Gaw Meem-designed Maisel’s Indian Trading Post in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Olive Rush with two paintings on her easel, from “Olive Rush, Pioneer Artist of Santa Fe” by W. Thetford LeViness, Desert Magazine, Nov. 1956

Although Rush had paintings in exhibitions around the country, the Depression years were financially difficult for her, a situation that was helped enormously when she began receiving mural contracts through the New Deal Works Progress Administration (WPA) program. She painted murals at the Santa Fe Public Library, New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, and at post offices in Oklahoma and Colorado. She also received private wall decoration commissions from wealthy female patrons in Chicago and Northern New Mexico. Among these were Mary Cabot Wheelwright, founder of the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe, and Florence Dibell Bartlett, founder of the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe. “So much of her mural work has been lost,” Gilmore notes. “It’s a product of the times, with changes to public buildings and private residences, but it’s a tragedy.”

“Three Birds,” Watercolor on Paper, 15 x 10.5 inches, 1954

Living in Santa Fe until her death in 1966, Rush never married. She had admirers and almost married in New York City, but “it was clear to her that she couldn’t have a role as wife and mother and also a career as an artist,” says Raphael, who sees Rush’s single status, along with her discomfort with self-promotion, as contributing to her relative obscurity. Without a husband or family to promote her artistic legacy, she was at a disadvantage, Raphael believes.

The artist’s parting gift to Santa Fe and her Quaker faith was to donate her home and garden to the Santa Fe Friends Meeting, which has preserved its historical quality and kept some of Rush’s furnishings and artwork on view. With the recent publicity the artist has received, Gilmore feels rewarded for her years of devoted scholarly effort. “I think we’re finally putting Olive in her rightful place,” she says.

“Sunset in the White Sands Deserts,” Oil on Board, 23.5 x 29.5 inches, 1949

No Comments