29 Dec Perspective: Edgar S. Paxson

In 1877, at Ryan Canyon in southwestern Montana Territory, a young man steps off the freight wagon he’s driving and into the wheel ruts of history. It is less than a year since the Battle of the Little Big Horn, only months away from the day Crazy Horse surrenders and is subsequently murdered. As the young man studies his surroundings, the dust that swirls around him already belongs to a new era — one he is not anxious to join. Even so, he has not traveled in vain, and in the years to come this wiry Easterner will play a major role in keeping the idea — the myth — of the Old West alive. Along with Frederic Remington and his future friend Charles Russell, he will become one of the “big three” Western artists, the third leg of a painterly stool set to prop up a wobbly and pistol-whipped past.

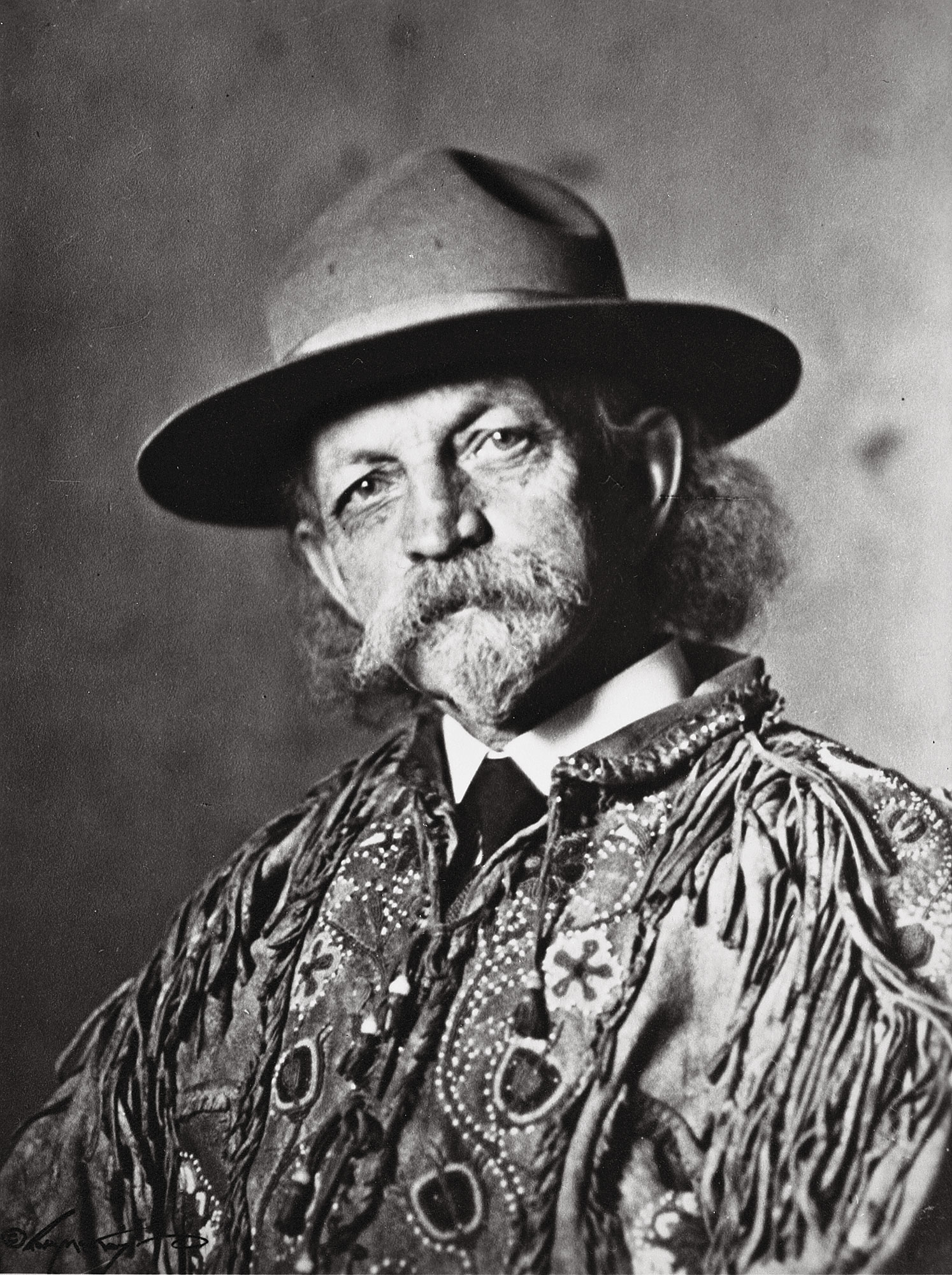

Edgar Samuel Paxson was born on the outskirts of Buffalo, New York, April 25, 1852. He had no formal training in art. No stranger to the smell of turpentine, however, he worked for his father’s sign and carriage painting business. Then, blown west by the novels of James Fenimore Cooper and the like, he landed a variety of “frontier” jobs, immersing himself in the lifestyle by working as an Indian scout, messenger and drover. To better fit the part, he even adopted the uniform: a fringed buckskin jacket. Living in Deer Lodge, Butte and finally Missoula, he would graduate from painting stage backdrops to portraits to eventually being commissioned to do murals for the Senate chambers in the State Capitol building in Helena and the A.J. Gibson-designed Missoula County Courthouse. His most famous work, Custer’s Last Stand, finished in 1899, would catapult him onto the national scene.

Custer’s Last Stand, originally titled Custer’s Last Battle on the Little Big Horn, is indeed Paxson’s masterpiece, a 6-by 9-foot stretch of canvas that includes more than 200 figures and is considered one of the most complete and perhaps most accurate presentations of the controversial happenings. Historical accuracy was foremost on Paxson’s mind during the 20 years he spent researching the topic that so fascinated him. “When Custer and his brave command met their fate on the Little Big Horn,” Paxson is quoted as saying, “I said, ‘Some time I will paint that scene.’ During my leisure hours I kept dabbling with brush. Each day I saw some improvement. In all this time, I never lost view of my object, and for 20 years gathered data, sifted and resifted it, conversed with participants on either side, visited the scene and became as familiar with the ground and the circumstances as with my own home.”

Paxson’s extensive research and personal contact with many of the participants ensured the details of arms, dress and equipment were all faithfully rendered, and from the outset, those who viewed the painting complimented him on his realistic depictions of Crazy Horse, Rain-In-The-Clouds, Crow-King and Two Moons, as well as Custer himself. Paxson famously includes a scene where an infantryman is seen extracting a jammed cartridge from his rifle with a pocket knife, an apparently common condition that in part may have led to the slaughter, while in the right foreground the half-breed scout Bouyer fires at the Ogallala chief Crazy Horse who was wounded three times in the battle. Even more importantly, Paxson shows Custer clutching not a saber, as so many “Last Stand” paintings have gotten wrong, but his wounded side.

Paxson’s love affair with the West was genuine and as time wore on he amassed a large collection of Indian artifacts, clothing and jewelry, a small museum in itself upon which he would draw from for historical authenticity. In fact, Paxson would create more than 200 images, a majority of them portraits of Indians, or Indians at their daily labor. At least twice he painted the translator and guide to Lewis and Clark, Sacajawea, and in both cases the Shoshone woman is depicted as essential to the expedition. Paxson also illustrated at least 10 books, and for a time wrote outdoor-related articles for the journal The American Field under the colorful pen name, ‘Pistol Grip.’

By the time Paxson moved to Missoula in 1906 he was supporting himself solely through his painting and in 1911 Paxson was commissioned to create six scenes relating to the Lewis and Clark expedition for the State Capitol building in Helena. Then the next year he was asked to do a series of eight murals for the newly erected County Courthouse in Missoula. Paxson, sunk up to his chaps in the perceived romanticism and heroism of the days gone by, apparently had no intention of creating high art, but instead tried to create more of a folk art, giving the residents of his adopted home a sense of place by locating them in history. University of Montana history professor, Dan Flores, speaking in 2000 at the Missoula Art Museum, called the way that Paxson commemorated the Lewis and Clark expedition in his art, “a vehicle in the direction of nativity.”

When the courthouse murals were finished, the public heaped praise on Paxson. One newspaper article, dated August 12, 1914, decided, “There were many old-timers among those who inspected the eight paintings representing western and Indian historical scenes. Some could not fully appreciate the artistic side of the works, but all did appreciate the accurate settings and were able to recognize the well-known characters among the Indians and the whites as depicted by the artist.” Colonel William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, a friend of Paxson, even puffed himself up to say, “There is no building of all its kind in all the country that can boast anything so good.”

But surely there was. As University of Montana professor of art history, Rafael Chacone noted, Paxson was never formally trained as a painter. His technique could be found lacking and he often had a problem with scale.

It would be fair to speculate that had Paxson been painting on the East Coast, it’s more than likely he never would have attracted the attention he did. Also, despite what the “old timers” might have said, the man obsessed with historical accuracy also managed to get many of the details, both large and small, wrong.

One notable example is in Lewis’s Detachment Crosses the Clark Fork River, where the wooden rafts are pegged and neatly lashed (which they would not have been), while the mountains behind are a near match for the dramatic and craggy Bitterroot range to the south instead of the low hills where the crossing actually took place. Discrepancies pop up in other paintings and the consensus seems to be that despite Paxson’s intimate knowledge of Western history and the Western experience, he couldn’t square it with his desire to conflate the scenes for dramatic effect and emphasize the heroic themes.

The microscope of history, of course, is harsh — the argument being that it should be. In an historical context, while Paxson was erecting his scaffolding for the capital murals, Picasso was in Paris inventing Cubism, and the contrast in art scenes couldn’t be greater. America, that dangerous and defiant infant, was at the time more of an idea than a nation, a vastness trying to carve out a definition of itself through violence and subjugation. The Western artists were there of course, but not so much as witnesses and recorders, but as ad men promoting a grandiose image of a West that only partially was. Paxson, in essence, was simply playing to the crowd, giving the nascent nation exactly what it was looking for.

There’s no arguing that the landscape and the time in which Paxson lived was (and is) dramatic, and that the awful history that goes with it makes for a good story. Exchange the microscope of history for the kaleidoscope of Hollywood, however, and as Professor Flores concludes, Paxson’s art becomes the precursor for the popularity of stars such as Gene Autry, TV shows like “Gunsmoke,” and the indelible and iconic Marlboro Man. It wouldn’t be until after Paxson’s death that the myths he helped create would begin to be dismantled, and a more honest look at what the West really was would come into view. From Montana’s standpoint, however, at the turn of the century, Paxson was a local boy who made good. A big fish in a small pond, Paxson stood out, shiny as one of the newly minted Indian head nickels he would eventually turn in his pocket. When Paxson died in Missoula on November 9, 1919, his friend Charlie Russell wrote an appreciation, saying in part:

“… Paxson has gone, but his pictures will not allow us to forget him. His work tells me that he loved the Old West, and those that love her I count as friends. Paxson was my friend, and today the west he knew is history that lives in books. His brush told stories people like to read.”

- Edgar Paxson

- “Lewis and Clark at Three Forks” | Edgar Samuel Paxson (1852-1919) | Oil on Canvas, 1912 Mural at Montana State Capital | Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society , Photo: Don Beatty, 10/99

- E.S. Paxson Studio in Butte, Montana, early 1900s. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society

- “Lewis’s Detachment Crosses the Clark’s Fork River, July 3, 1806” | Edgar Samuel Paxson (1852-1919) | Oil, 1914 | Missoula County Art Collection | Photo: C. Basner, Courtesy Missoula Art Museum

No Comments