29 Dec Perspective: Nick Eggenhofer [1897-1985]

“The thing that is so little understood is the Western theme is so immensely broad, as big as the country itself,” Nick Eggenhofer once said. “To write about it is one thing, but to draw it is another.” And draw it, he did. With unmatched historical accuracy, a meticulous commitment to detail and a passion for all things Western, his illustrations and paintings depict indelible images of the frontier: Native Americans in buckskin dress and ponies pulling travois, or the bullwhacker walking alongside his 12-yoke team of oxen, or the angles, curves and rigging of a Pony Express saddle.

Nick Eggenhofer belonged to the generation of fine Western artists who emerged after the deaths of Remington and Russell and who link classic Western artists of the past to contemporary artists. As a young artist in New York City, he learned to draw and paint the West as it was depicted in magazines, books, motion pictures and photos. But before that, Eggenhofer had first steeped himself in the lore of the American West as a boy in his hometown of Gauting, Germany.

In Gauting, Eggenhofer had thumbed through Street and Smith’s Buffalo Bill Weekly, a popular U.S. pulp magazine translated into many languages. At the local movie house, he had watched his favorite film, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, roll across the screen multiple times. In Munich in 1909, the featured cowboys and Indians in a bona fide Wild West show mesmerized young Eggenhofer. So the die was cast for the future Western pulp magazine illustrator who, at the height of his career, would become known as “King of the Pulps.”

But Eggenhofer first had to get to America. Grandfather Eggenhofer paid the passage, and 16-year-old Nick arrived at New York Harbor on December 10, 1913. Learning the English language along with maintaining financial obligations to his American guardian, Uncle Peter, and his family back in Germany, kept Eggenhofer rooted in New Jersey. While working a variety of jobs, tantalizing images of the West appeared in the oddest places. In his autobiography, Horses, Horses, Always Horses: The Life and Art of Nick Eggenhofer, Eggenhofer wrote of an astonishing sight on Coney Island. “I spied a small cavalcade with cowboys and Indians on horseback led by none other than Pawnee Bill. His show had cowboys, Indians, a stagecoach, a replica of a real western town, and everything else necessary for a good western show.” At Guy Weadick’s Wild West show on Long Island, Eggenhofer was invited to go behind the scenes where he scrutinized a stagecoach and mingled with cowboys, Indians and horses. “I was totally absorbed in observing every aspect of western life,” he wrote.

Eggenhofer was drawing and painting, but formal training at established art schools was unaffordable. Someone suggested Cooper Union. He enrolled in the free institution in 1916 and attended night classes for four years. During the day, the lanky, dark-haired art student apprenticed at American Lithograph Company earning $3 a week. In 1920, Eggenhofer sold three watercolors depicting Western life for $25 a piece. No doubt making his first sale as an artist was momentous and thrilling, but he must have seen, too, the irony of selling those watercolors to Street and Smith, the firm that published Buffalo Bill Weekly, the very pulp Western magazine he had read cover to cover in Gauting.

In late 1920, a strike at American Lithograph sent Eggenhofer back to Street and Smith. He was hired and began cranking out black-and-white dry-brush illustrations for the weekly pulp magazine Western Story. Quality illustration, believable stories and good writing pushed the periodical to a peak circulation of 500,000. As for the pulp magazine industry itself, founding credit is given to Frank Munsey who published the first pulp in 1896. By 1905, hundreds of pulp magazines — so named for the use of low-grade paper — appeared on the newsstands every week. The volume created an enormous and frantic demand for supporting artwork.

Meanwhile, Eggenhofer pored over books and illustrations in local libraries, carefully researching the men and women, the animals and the equipment, that had settled the West. In his New Jersey studio, he squirreled away hundreds of pictures depicting the frontier. He acquired authentic props: guns, chaps, Indian headdresses, tools and other Western paraphernalia.

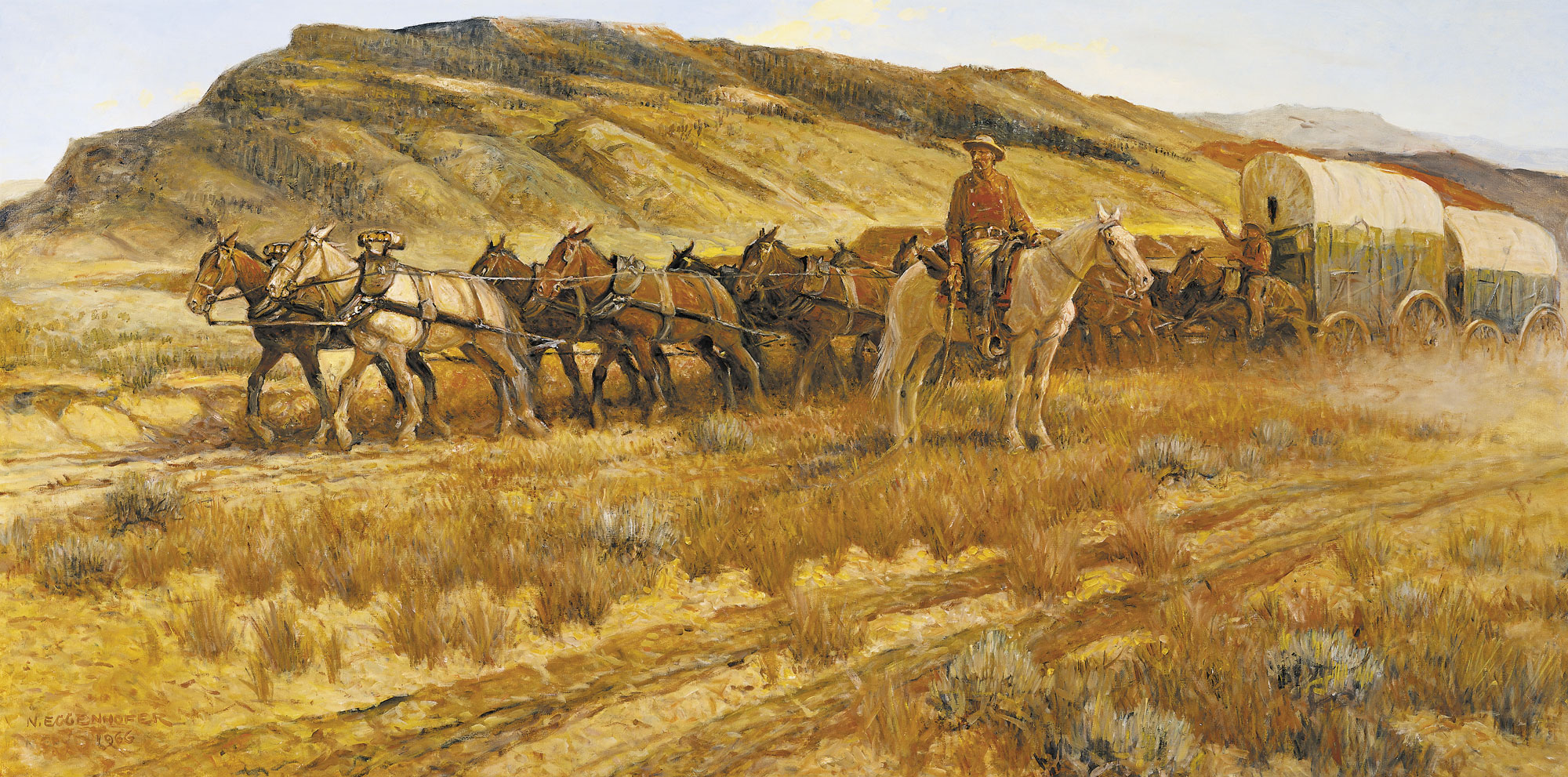

With pen, ink and brush, Eggenhofer captured a hardscrabble history teeming with adventure and romance. He became particularly adept at illustrating modes of early Western transportation, even building scale models of everything from stagecoaches to freight wagons to Red River carts to ensure the historical accuracy of his work. The Bone Pickers, an undated 12-by-16-inch watercolor, is a narrative piece that focuses on two Metis and their Red River carts. Eggenhofer portrays the men picking up buffalo bones among tufts of prairie grass. His brushstrokes capture the cart’s wooden construction, its wheel linchpins, tapering side beams that served as shafts, “uprights” inserted into a top rail and the simple harness of rawhide straps suspended from a wooden saddle.

“He knew his subjects so well,” says Eggenhofer collector Ernest Fuller. “If 10 paintings by 10 Western artists were lined up alongside each other, you’d know the Eggenhofer by the style and detail, and especially the attention he gave to depicting wagons and other conveyances. The older Western artists and collectors, they’ll study Eggenhofer’s work to understand the accuracy his work entailed and his dedication.”

In 1961, Eggenhofer channeled his knowledge into a book he both wrote and illustrated, Wagons, Mules & Men: How the Frontier Moved West. Book collectors now prize the detailed, comprehensive book that chronicles the modes of transportation paramount to Western expansion.

With success as an illustrator, Eggenhofer finally had the financial means to marry his long-time fiancée, Louise, in May of 1924. At once they began making plans for a trip West. In 1925, they drove their Model T over dirt and gravel, mud holes and chuckholes, traveling 20 to 25 mph, eventually reaching Santa Fe and Taos, Albuquerque and the Grand Canyon. He relished vestiges of the Old West: Mexicans, Indians, gritty old-timers and burros bringing in loads of firewood. The vast, isolated desert and mountains moved him. Eggenhofer wrote of his long-anticipated trip West, “My work took on a new perspective, a new dimension, a new point of view.” Encounter of Crow and Blackfeet Indians, a 28-by-22-inch oil on canvas dated 1944, offers Eggenhofer’s historically accurate storytelling but also evokes mood, thick with the sounds, strength and drama of clashing horses, raised weapons and two warriors engaged in battle.

Throughout the 1920s and into the ’40s, Street and Smith and other pulp publishers couldn’t get enough of Eggenhofer’s Western vignettes, double-page spreads and cover art depicting frontier transportation, gunslingers and gunplay, cowboys at work and play, Indians and more. He managed to illustrate 50 books and an equal number of dust jackets. Each book and each piece of published artwork further advanced his reputation as an illustrator. Even when the national economy sagged and publishers cut the price for artwork, Eggenhofer kept busy during the worst of the Depression. Few artists matched him for the authenticity and raw honesty of his subjects.

As for the pulps, they had survived the Depression and the war years, but they couldn’t compete with radio, television and advancements made in photography. Thus, the great era of illustration came to an end in the mid-1950s.

Eggenhofer estimated he produced more than 30,000 drawings for Street and Smith and other pulp publishers. According to Eggenhofer, the original artwork legally belonged to the artist and was supposed to be returned, but most drawings often languished in magazines’ arts department. He wrote that almost anybody could dig into the pile of illustrations and help him or herself to whatever they wanted. Eggenhofer himself lost track of his original artwork and claimed to have only 20 or so of his original drawings. “I just don’t know where they all are,” he wrote. Eggenhofer’s commercial work from the pulp years does turn up in galleries. Peter Riess at the Gerald Peters’ Santa Fe gallery says, “There is a small market for Eggenhofer’s pen and ink illustrations but the work has little value.”

Eggenhofer next shifted his energy to illustrating national publications. He did more easel painting but marketing the finished work was problematic. In the East, there was little interest in Western art. By 1960, the Eggenhofer’s only child, Evelyn, was in college; his pulp career was finished. He was no longer bound to the East. Dr. Harold McCracken, the founding Director of the Whitney Gallery of Western Art in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming, gave Nick and Louise the final nudge to move West. Impressed by Eggenhofer’s talent, he suggested the couple “come out to Cody and see what we have.” They did and liked it. In November of 1961, the Eggenhofers left the East for good and settled in Cody, bringing Nick’s life-long passion for the American West full circle.

Influenced by the light, color and landscapes in Wyoming, Eggenhofer produced highly esteemed watercolors and oils for Western galleries, private collectors and the National Park Service. The nature of his work changed dramatically, becoming broader in scope and color, and more imaginative and compelling. In the book Fifty Great Western Illustrators, author Jeff Dykes describes Eggenhofer’s style: “ … strongly reminiscent of Russell’s, but considered tougher and more impressionistic in feeling. The artist also employed a very broad color range, often placing stitchlike strokes of pure color side by side so as to create an animated effect.”

In 1971, the Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center in Oklahoma City featured Eggenhofer illustrations and fine art in an exhibition entitled Fifty Years of Painting the West. Two years later he was awarded the National Cowboy Hall of Fame Trustees Award for Outstanding Contribution to Western Art. In 1975 and 1981, the Buffalo Bill Historical Center hosted Eggenhofer exhibits. He summed up the recognition and accolades this way: “I have found throughout my years of illustrating and art work, and in life, imagination must precede accomplishment. And, in between, there’s a hell of a lot of sweat, work, long hours and learning.”

Most recently, in 2008, the Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe and the High Desert Museum in Bend, Oregon, hosted Eggenhofer exhibitions.

Bob Boyd, curator at the High Desert Museum, says “Nick Eggenhofer’s art is valued because he chose to focus on a segment of frontier life that often appears only as a backdrop to the lives of Native Americans, explorers, cowboys and pioneers. His detailed paintings based on a lifetime of careful study make Eggenhofer a true artist-historian.”

At auction, Eggenhofer’s art consistently brings higher prices than anticipated. For instance, at the 2007 Coeur d’Alene Art Auction, Wagon Boss, a 28-by-56-inch oil brought $61,600, a world-record price for an Eggenhofer work. That same year at the Santa Fe Art Auction, Trapper on Horseback, a 16-by-12-inch gouache on paper netted $9,600, exceeding the estimated $6,000 to $8,000. Says Fuller, “Collectors are finally appreciating the accuracy and detail of his work, and it is steadily rising in value.”

The newfound appreciation for Eggenhofer’s work and the recent museum and gallery exhibits are fitting tributes to the “King of the Pulps” who once mused how writing about the West was one thing, but to draw it was another. Says Riess, “His oils depicting dramatic Western scenes are increasingly valued. Collectors can still buy a large work for under $100,000. While you can’t put him in the same category as Russell or Remington, Eggenhofer was very attentive to detail in his compositions, and people who were familiar with the frontier scenes he depicted commended his work. Still, it’s too early to know what his legacy will be, or if he’ll have a legacy.”

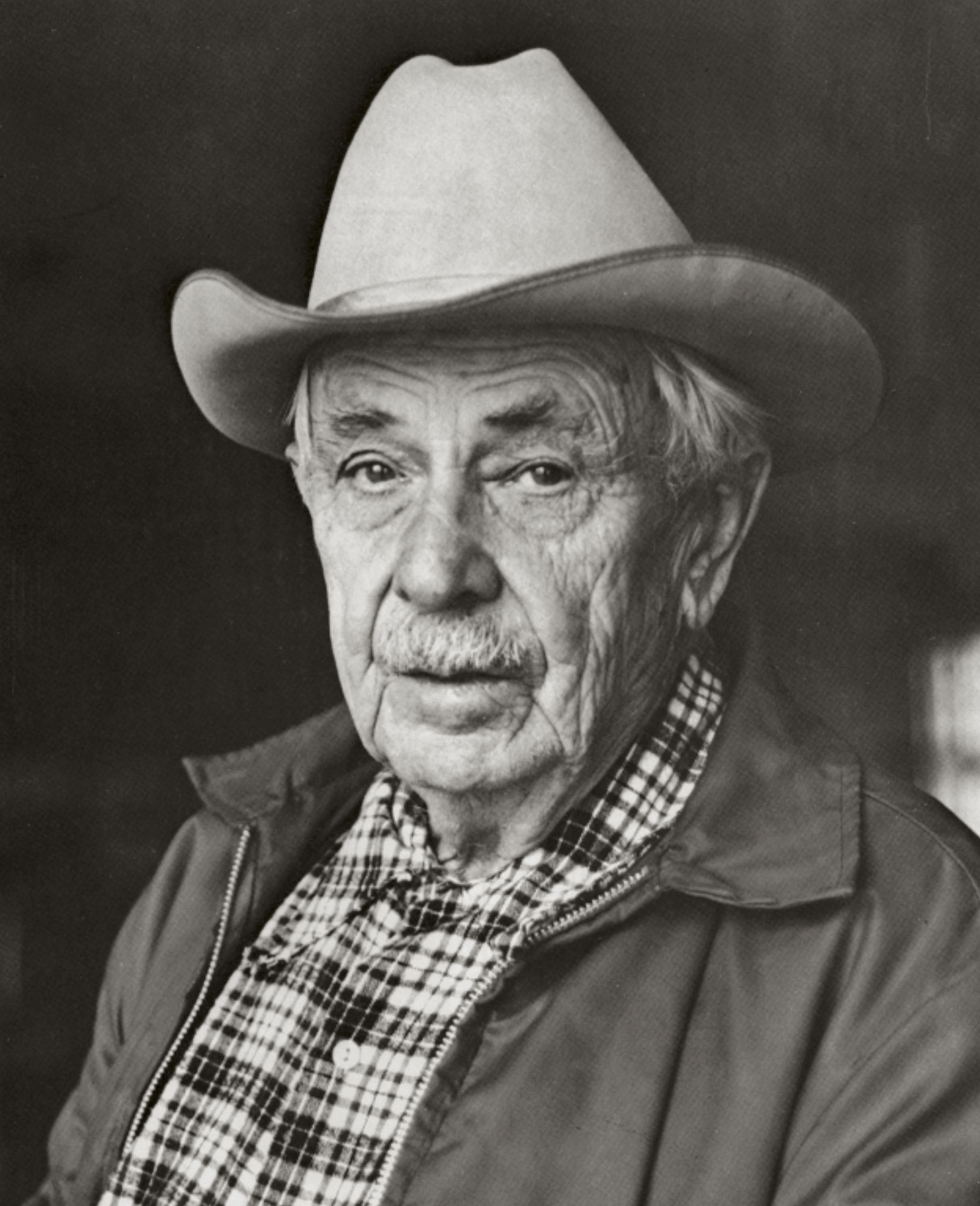

- Artist Nick Eggenhofer

- “Encounter of Crow and Blackfeet Indians” 1944 | Oil on Canvas | 28 x 22 inches

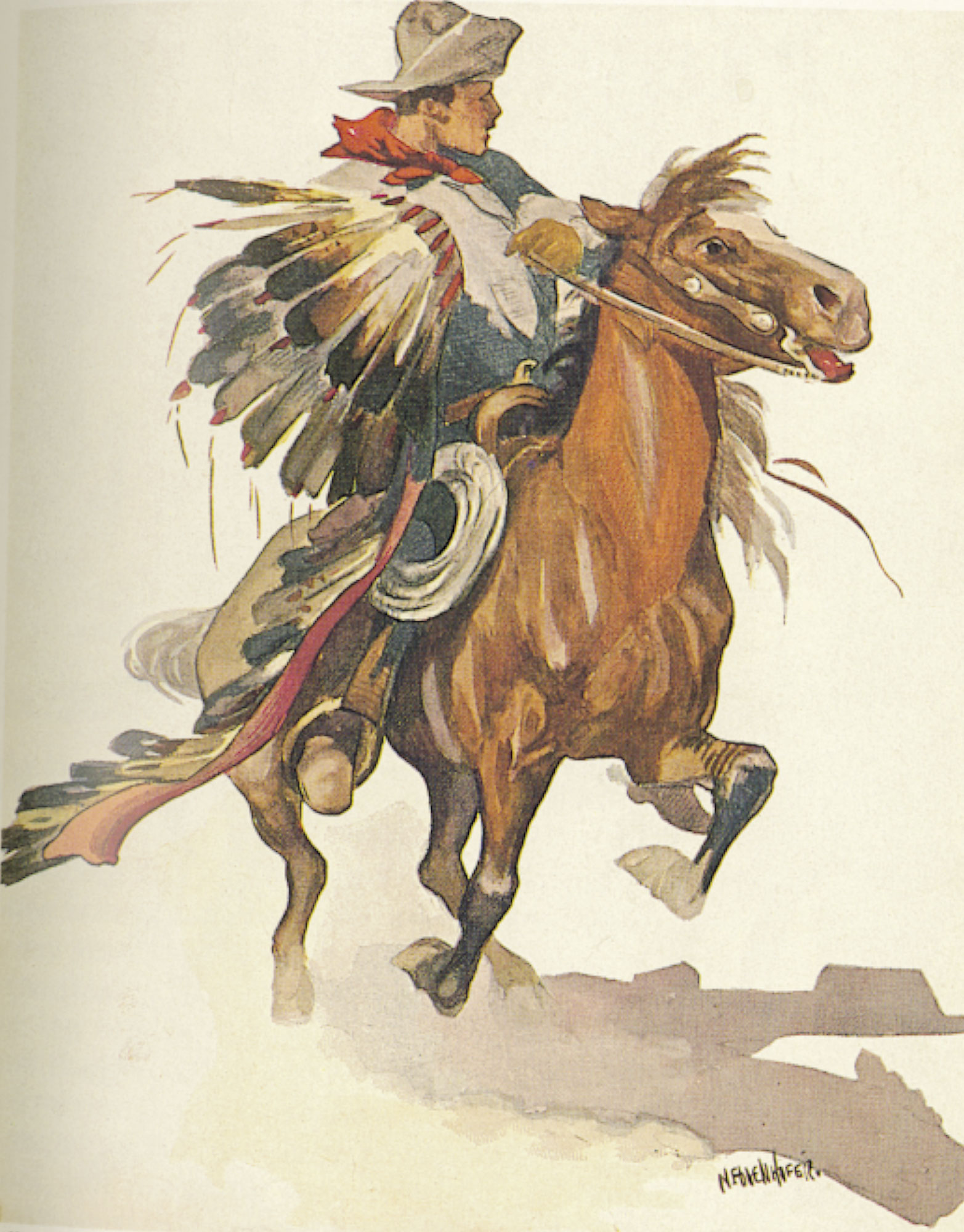

- Full color illustration sold to Street and Smith, c. 1920. (Images courtesy of Sage Publishing Co., Inc. Cody, Wyoming)

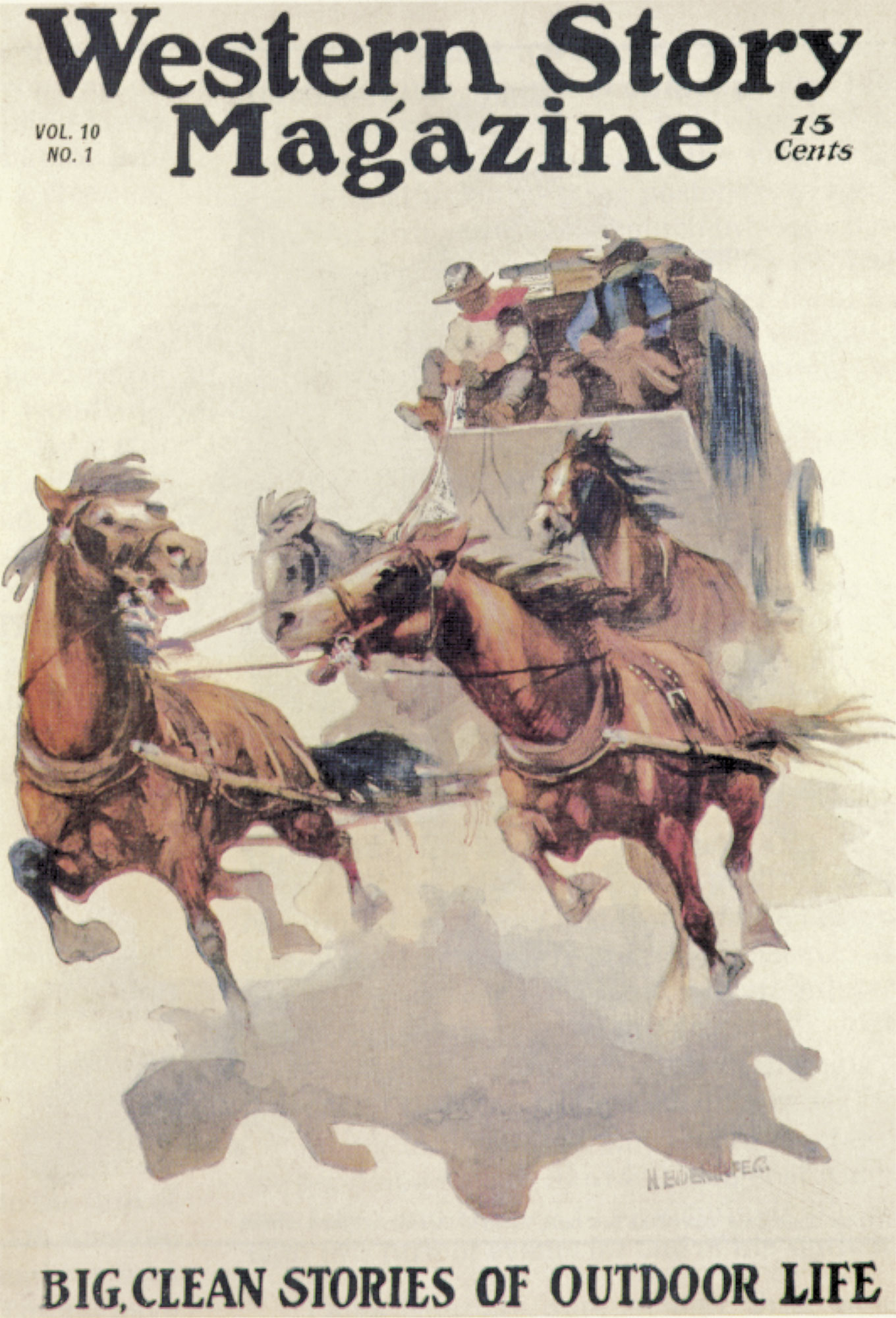

- Cover of Western Story Magazine — the illustration was one of the first sold to Street and Smith. It was Eggenhofer’s first published piece at 23 years of age, c. 1920.

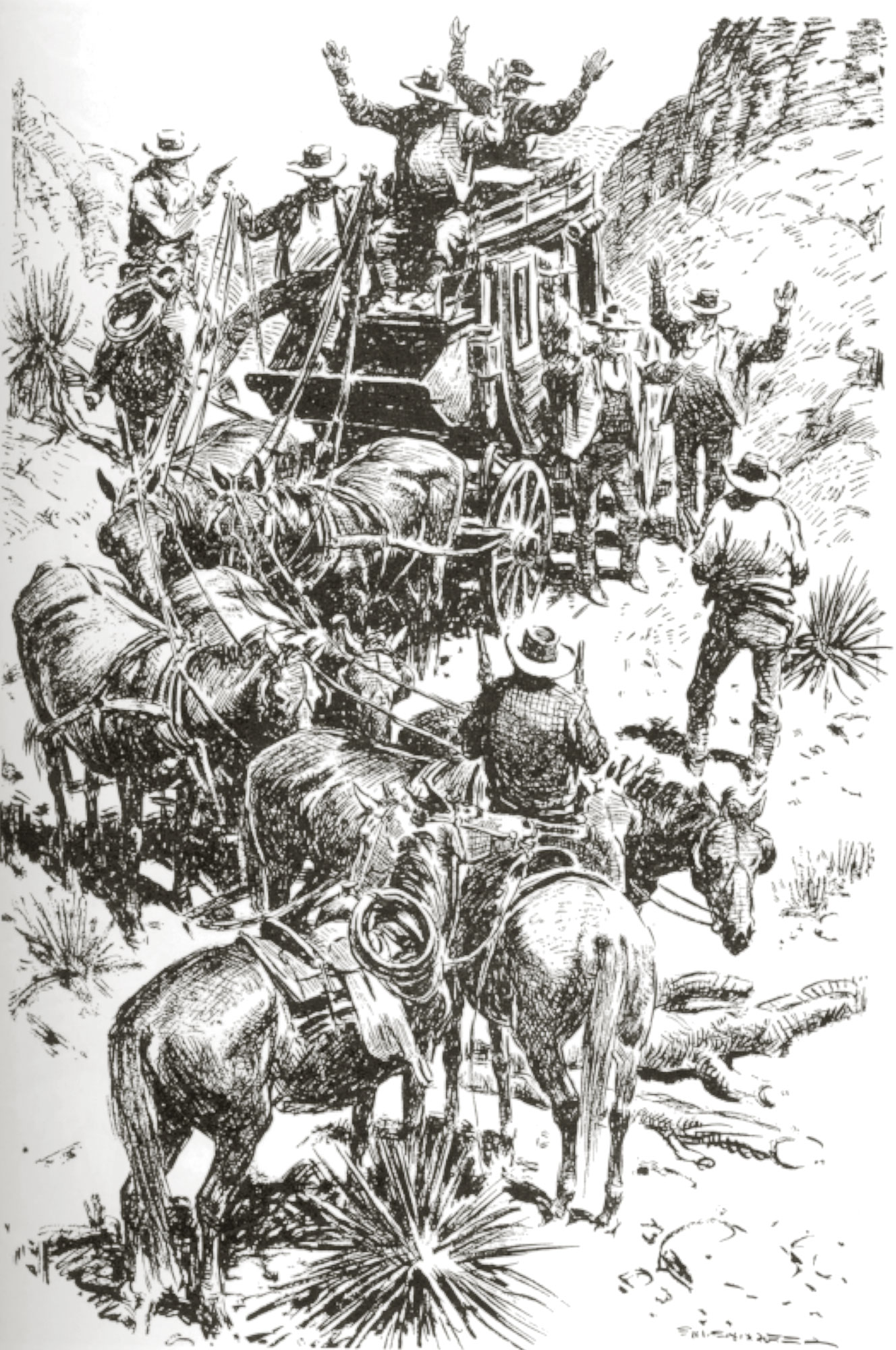

- Black and white illustration for Street and Smith, c. 1941. (Image courtesy of Sage Publishing Co., Inc. Cody, Wyoming)

- “Wagon Boss” 1966 | Oil on Canvas | 28 1/4 x 55 1/4 inches

No Comments