16 Jul Luke Frazier: A Kinship with Wildlife

ONE OF THE MORE IMPORTANT AND IMPRESSIVE ENTRIES on wildlife artist Luke Frazier’s resume is his age. At only 48 years old, Frazier has produced a body of work with a breadth and maturity that would be the envy of an artist much further along in life. Still, having picked up the brush late in high school, Frazier has put in 30 years at the easel, most of them measured in long, dedicated hours.

“The Tillamook Creel” | Oil | 18 x 40 inches

A typical day for Frazier starts before 7 a.m. and might not end until supper around 6 p.m. It’s clear from conversations with him that art and life, as he experiences them, are complementary parts of a seamless whole. “There’s no secret to it, to the way I paint,” Frazier says. “I paint the stuff I live — hunting, fishing, the outdoors. It’s just a lot of trial and error and doing it, and I know I’ll never stop learning.”

Alan Fama, of Fama Fine Art in Houston, Texas, thinks that Frazier has achieved prominence at an early age precisely because of his diligent work ethic: “Before you can make a great painting, you’ve got to be able to draw, and Luke has put in the time drawing. He’s an artist in the purest sense — there’s no other job for him, and he knows it. He lives it.”

Frazier graduated high school in 1988 and started junior college at Dixie State University in St. George, Utah, assuming he’d become an engineer like his father. During his first year there, he won best of show at the university’s annual art show. “The prize was 500 bucks — and before long, I was trading paintings to the dean for my tuition,” Frazier says. But the epiphany came when art professor Del Parsons pulled him aside and said, “Luke, you need to be an artist.” Frazier graduated with an associate’s degree in science, but went on to Utah State University, earning a bachelor’s of fine art in painting and a master’s of fine art in illustration in 1993.

“Up Close and Personal” | Oil | 30 x 40 inches

The connection between Frazier’s early career and his current ascendance is nicely crystallized by his presence in Diane K. Inman’s book, The Fine Art of Angling: Ten Modern Masters. He’s not only one of the featured 10 artists, but his painting The Tillamook Creel adorns the cover of the book.

“I used to do a lot of illustration work,” Frazier explains. “I used to do a monthly illustration for Alaska Magazine, and a lot of work for Big Sky Journal. I was trained as an illustrator and learned from some of the great artists who also spent time as illustrators — Philip Goodwin, Leon Parsons, Bob Kuhn, Bob Abbett. These guys were masters.”

In the early 1990s, Frazier was doing a lot of fly-fishing paintings and illustrations (many of them cast in early morning with mysterious lighting and tone — what Frazier aptly calls “caddis-fly light”) when the Robert Redford film “A River Runs Through It” hit the silver screen in 1992. Interest in Frazier rocketed. “That movie was largely about nostalgia, and it so happened that a lot of my paintings featured old creels I collected — artifacts from a vanished era.”

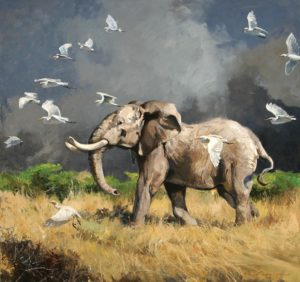

“Old Three Toes” | Oil | 26 x 30 inches

“Old Three Toes” | Oil | 26 x 30 inches

A few years before, when Frazier was 19, he drove up to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, with a clutch of paintings and met a pair of collectors outside the National Museum of Wildlife Art. “I laid my paintings out right there on a snowbank and the couple said, ‘How much for all of them?’ That was a big break for me. Most of the galleries I had gone around to would look at my work and say, ‘Yeah, it’s good. But do 50 more paintings and then come back.’” Between Frazier’s indefatigable work ethic and his sincere dedication to learn from the artists he admires, he’s profited from a self-directed course of study.

“Black Death” | Oil | 30 x 36 inches

In the early 1990s, he traveled to Tucson, Arizona, to meet Bob Kuhn, for example. “We hit it off right away, and I studied with him and learned from him for 25 years.” Frazier recalls a moment when Kuhn recognized the influence of Russell Chatham on Frazier’s early work. “Bob asked me, ‘Don’t you ever paint blue skies?’” Frazier also credits Robert Abbett as a tremendous influence: “I started out trying to paint every blade of grass, for example. But Abbett taught me techniques that don’t depend on that detail for effect. These gentlemen were so generous with their time and tutelage.”

A predilection for drawing intimately links Frazier to the earlier generation of artists and illustrators. Greg Fulton, managing partner at Astoria Fine Art in Jackson Hole (where Frazier will have a solo show in September) notes: “Whereas a lot of artists now rely on photography and work from a photograph, Luke still does it the old way — drawing everything first. So, he’s less of a ‘slave to the reference,’ as they say. What’s in his mind comes out through his pencil and brush. He is able to produce a really compelling painting because it’s made from scratch.”

“El Primo” | Oil | 36 x 36 inches

Frazier is adept at sculpture as well, and he credits his ability to visualize wildlife “in the round” as an asset when it comes to flatwork. “Sculpture taught me to see form,” Frazier says. “It’s easier for me to go from 3-D to flatwork because I’m really sculpting and drawing with the brush.” Fulton concurs: “Like Bob Kuhn, Luke knows animals extremely well. He spends countless hours in the field and knows his subject matter.”

It’s an integrative approach: finesse with sculptural techniques honed his efforts to conceive of the subject matter in three-dimensional form, and his expertise with the pencil clarified his brushwork. “I do use pencil, but I want to see form, and achieving that is simply faster with a brush,” he explains. “But it’s all drawing. For example, lately I’ve gotten really into Japanese calligraphy, which is all about the opacity of pigments and the brushwork. I tell people that I draw with paint.” Something the sculptor Edward Fraughton once said about anatomy also resonates with Frazier and guides his approach: “Fraughton said, ‘Know where the ends of the bones are and let the middles take care of themselves.’ I think about that all the time.”

Frazier is refreshingly forthright and eloquent as he shares his philosophy on life and art. “It has to be more than just animals on canvas,” Frazier says. “I want to tell a story through painting those animals.” He lists Charlie Russell as an artist whose genius is revealed in the emergent properties that evolve from experience, technique, and vision of a story that all perfectly integrate on the canvas. “Charlie Russell’s genius lay in the nuts and bolts, the little imperfections and mistakes that tell the story,” Frazier says.

In addition to exhibiting work at the Prix de West in June and the Coeur d’Alene Art Auction in July, Frazier will exhibit work during the Jackson Hole Art Auction, September 14 and 15.

“Colors of Costa Rica” | Oil | 14 x 16 inches

“Colors of Costa Rica” | Oil | 14 x 16 inches

“Luke Frazier is the top sporting dog artist out there right now,” remarks Fama. “When Robert Abbett died, he left a void in the sporting art world, and it looks like Luke has been chosen by the major collectors to fill it.”

As an example, Fama points to Frazier’s Up Close and Personal, a 30-by-40-inch painting of a pair of dogs with quail, which sold for $35,700 in 2016. “That painting went for quite a bit more than expected at the Coeur d’Alene auction,” Fama says.

Frazier himself understands that accomplishment depends on effort, as in the old musician’s joke about how to get to Carnegie Hall: practice, practice, practice. For Frazier, it is draw, draw, draw. “You don’t become a master overnight,” he says. “It’s mileage — so much mileage. I’ve hammered away at it, really worked at it. But the thing is — I love doing it; it’s my life.”

No Comments