16 Jul Perspective: T.C. Cannon [1946–1978]

With 50 years of modern American art in the rearview mirror since the 1960s, it may be difficult to grasp how radically the work of one young Native American painter at the time diverged from what had come before, and the impact his vision would have on Native artists who came afterward.

Tommy “T.C.” Cannon, c. 1966 | Image courtesy of IAIA Archives, Santa Fe, New Mexico

To set the scene: When Kiowa-Caddo painter T.C. Cannon [1946–1978] entered the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe in 1964, two years after the school opened, Native American painting for decades had been known for images of traditional ceremonial and daily life, most of which could have been plucked from the previous century.

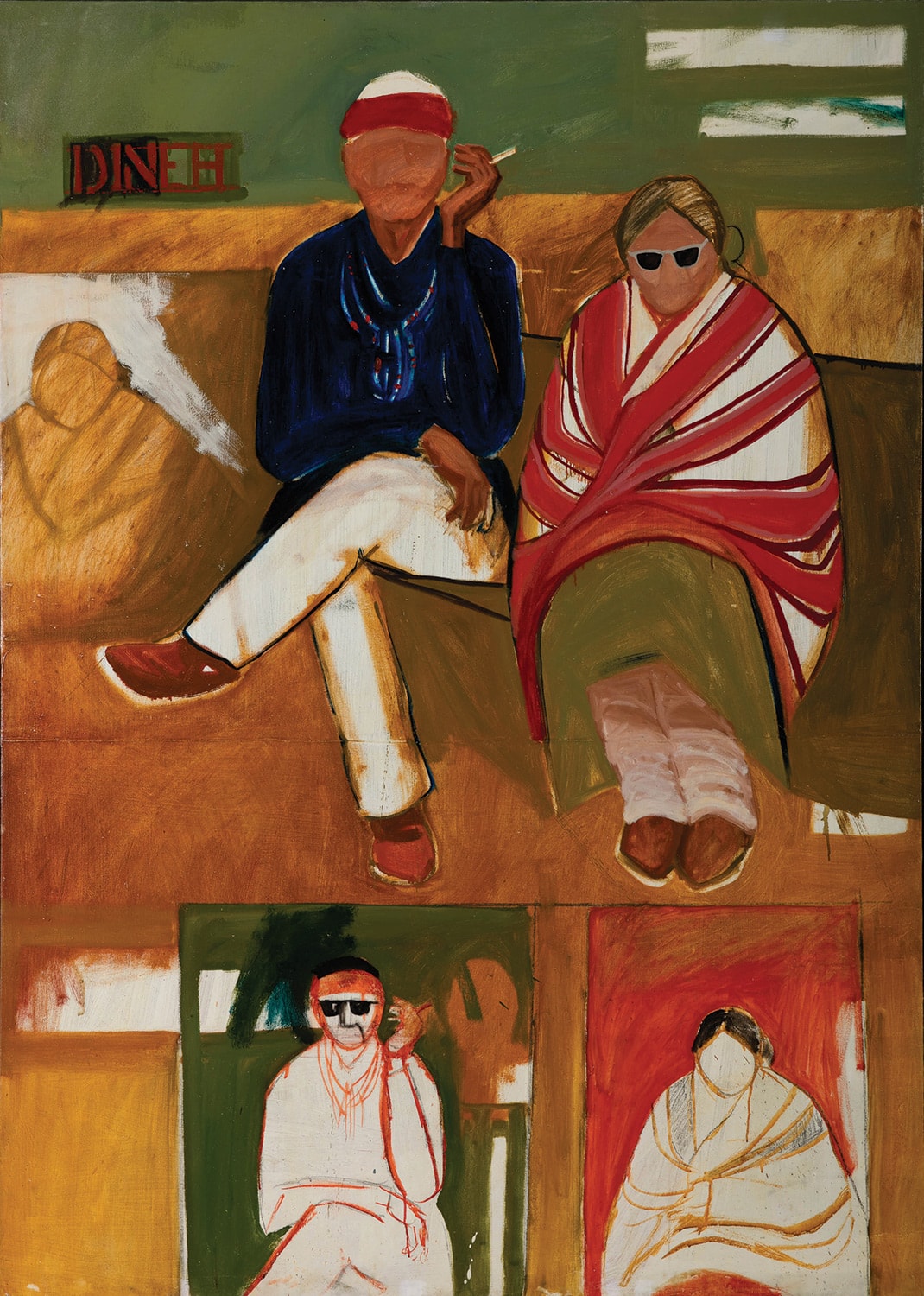

“Self-Portrait in the Studio” | Oil on Canvas | 1975 Collection of Richard and Nancy Bloch | © 2017 | Estate of T. C. Cannon | Photo by Addison Doty

In Cannon’s home-state of Oklahoma, a group of early-to-mid-20th-century Kiowa painters, known as the Kiowa Six (Spencer Asah, James Auchiah, Jack Hokeah, Stephen Mopope, Lois Smoky, and Monroe Tsatoke), had gained international recognition for work featuring delicate lines, solid colors, and two-dimensional imagery of dancers and mounted warriors on minimal backgrounds.

In the Southwest, Native artists were painting in a similar flat, narrative style promoted through the Dorothy Dunn Studio, which opened in the early 1930s at the Santa Fe Indian School. Working in gouache and colored pencil on paper, these painters were encouraged to depict dances, pottery making, and other scenes of everyday life from their home pueblos or reservations. A few became known for lyrical paintings of stylized deer and birds, which some mid-1960s IAIA students called “Bambi art.”

Then, as a student at IAIA, Cannon began creating pieces such as Mama and Papa Have the Going Home Shiprock Blues (1966). Here, suddenly, was a huge canvas — 84 by 60 inches — in shockingly bold colors, incorporating repeating and intentionally unfinished imagery, stenciled words, and a larger-than-life Diné (Navajo) couple whose dress and appearance placed them in an ambiguous timeline between traditional and present-day.

Here was an awareness of Pop Art, Abstract Expressionism, and other American art movements of the day. And Cannon’s paintings also reflected a complex conversation going on, within the artist and in larger American society, about identity politics, historical and contemporary Native experience, and indigenous voices speaking for themselves.

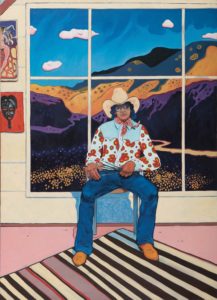

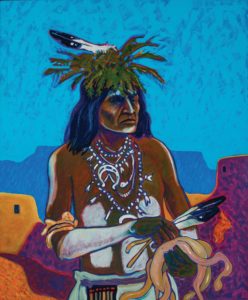

“Two Guns Arikara” | Acrylic and Oil on Canvas | 1974–1977 | Anne Aberbach and Family, Paradise Valley, | Arizona | © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon | Photo by Thosh Collins

“Two Guns Arikara” | Acrylic and Oil on Canvas | 1974–1977 | Anne Aberbach and Family, Paradise Valley, | Arizona | © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon | Photo by Thosh Collins

“Cannon’s work was ‘very of the moment,’” says Karen Kramer, curator of Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture for the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. “It was a real pivot from the idea of Native people trapped in the past.”

Kramer is curator of the traveling exhibition T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America, organized by the Peabody Essex. In July, the show opened at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where it continues through October 7. It then moves to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York City in March 2019, and runs through mid-September 2019. A look at the breadth and depth of Cannon’s intellectual and creative interests and modes of self-expression, the exhibition includes some 90 paintings and works on paper, as well as examples of his poetry and music.

“Soldiers” | Oil on Canvas | 1970 | Collection of Arnold and Karen Blair © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon | Photo by Scott Geffert

Born Tommy Wayne Cannon and later known as T.C., Cannon absorbed the tradition of his father’s Kiowa and his mother’s Caddo heritage. His Kiowa name was Pai-doung-u-day, which translates into One Who Stands in the Sun. His early years were spent on his father’s family’s tribal allotment near the Wichita Mountains in Southern Oklahoma, where he helped pick cotton in summer. Later, the family moved to the small, mostly white farming community of Gracemont, Oklahoma. Although his high school had no formal art program, Cannon was intensely interested in drawing and painting. He studied art on his own, became acquainted with several Kiowa artists, and saw murals by members of the Kiowa Six. As a teen, he took first place in regional art contests four years in a row.

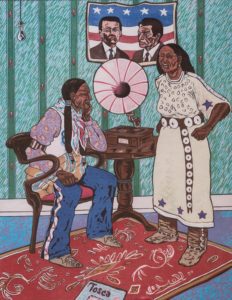

“A Remembered Muse (Tosca)” | Woodcut |1978 Anne Aberbach and Family | Paradise Valley, Arizona © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon | Photo by Thosh Collins

Enrolling in IAIA following high school, Cannon arrived at the perfect time. It was a period in the school’s early history known as the “golden age.” Bringing together students from tribes all over North America, the school encouraged a progressive educational model that emphasized experiential learning and self-expression. The art faculty then was comprised of both Native Americans, including Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache) and Fritz Scholder (Luiseño), and non-Native American instructors such as painter Seymour Tubis and Hans Hofmann.

It was an atmosphere of enormous creative vitality that reflected the social and political upheavals of the 1960s. At the same time, notes IAIA Archivist Ryan Flahive, there was the added dimension of IAIA students encouraged to understand and take pride in their “Indian-ness,” as Lloyd Kiva New, then-director of IAIA, frequently reminded them. Traditional arts as well as avant-garde movements from the East and West coasts were represented by IAIA instructors, while the many-cultured mix of Native students learned immeasurably from each other.

Cannon, described as a complex and often quiet personality, drew fellow students around him like a magnet. He filled countless notebooks and sketchbooks with observations, reflections, poetry, and drawings. He taught himself guitar and harmonica and was captivated by Bob Dylan, although his musical tastes were wide ranging, from folk to opera, rock, and country. His personal reading list was equally eclectic, including stacks of books on philosophy, art history, literature, and poetry. As documented in the 1995 book, T.C. Cannon: He Stood in the Sun, by Joan Frederick, Cannon later wrote to his friend and former IAIA dorm counselor, Robert Harcourt, “As a person curious to all of life, ancient or contemporary, I find that as an artist, it is even more important to touch every turnable leaf of knowledge.…” From this rich confluence of cultural, political, social, and personal circumstances emerged works that broke the mold for Native painting, reckoning with American history from an indigenous perspective yet also expressing elements of shared human experience. “He puts Native and American history up against each other and they overlap. It’s not just about binaries, not just us and them. It becomes a larger conversation that has to do with politics and humanity,” Kramer says.

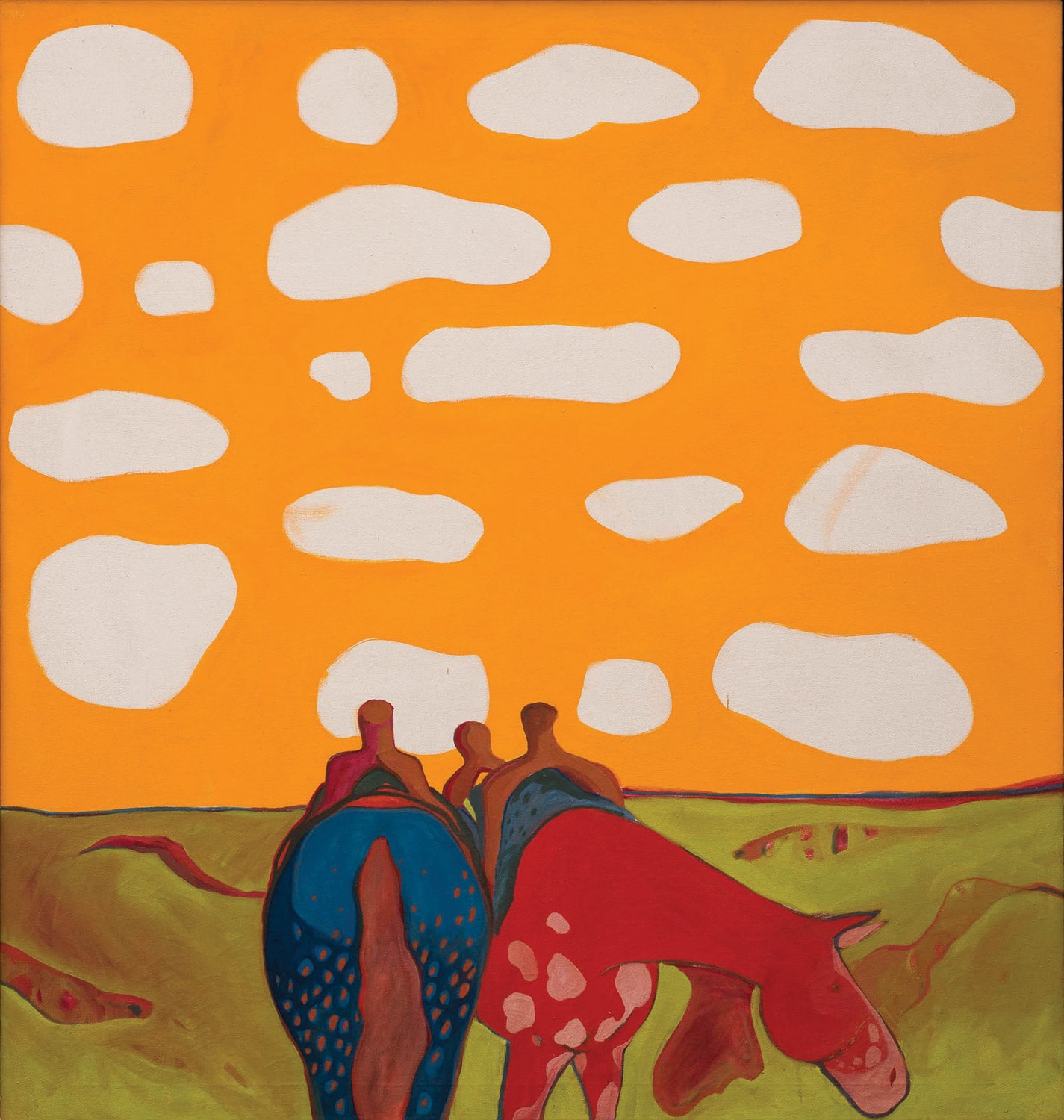

“All the Tired Horses in the Sun” | Oil on Canvas | 1971–1972 | Tia Collection | © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon

“All the Tired Horses in the Sun” | Oil on Canvas | 1971–1972 | Tia Collection | © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon

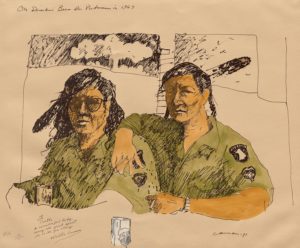

Complicated human and tribal feelings became interwoven as well in Cannon’s two years in Vietnam with the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division (the “Screaming Eagles”). He voluntarily enlisted in 1966 after a brief stint at the San Francisco Art Institute, where the free-flowing instructional approach at the time left him artistically unsatisfied. War contradicted his natural pacifist sensibility, yet he also carried the pride and honor of the Kiowa warrior tradition. In 1970, Cannon and his father, Walter, a World War II veteran, were both inducted into the esteemed Kiowa Black Leggings Warrior Society.

After leaving the Army in 1969, Cannon returned to Oklahoma, married — he divorced a few years later — and spent three years at Central State University in Edmond (now the University of Central Oklahoma). While a student there in 1971, he received his first solo museum exhibition at the Southern Plains Indian Museum in Anadarko. The following year, the National Collection of Fine Arts (now called the Smithsonian American Art Museum) invited Cannon to be half of a major, two-artist exhibition, Two American Painters: Fritz Scholder and T.C. Cannon. From there, followed national and international acclaim, and soon, exclusive representation by New York City art dealer Jean Aberbach.

“Small Catcher” | Oil on Canvas | 1973–1978 Collection of Christy Vezolles and Gil Waldman | © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon | Courtesy of the Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona | Photo by Craig Smith

After graduating from Central State, Cannon returned to Santa Fe, a place that held his heart. His creative energy was in high gear, flowing out as paintings, drawings, music, and writing. He worked with a Japanese master woodblock carver and a Japanese master printer. Through Aberbach’s involvement in the Santa Fe Opera Guild, half of the edition of Cannon’s 1977 lithograph, Anadarko Princess, was sold as a fundraiser for the opera. In 1977, the artist also completed a major mural for the Seattle Arts Commission.

On May 8, 1978, Cannon was killed in a car wreck near Santa Fe. For years he had told friends, to their dismay, that he didn’t believe he would live past 31. He was four months shy of 32 when he died.

“On Drinkin’ Beer in Vietnam in 1967 Posthumous Edition” | Handpainted Etching (after 1971 drawing) | circa 1988–1989 | Collection of Irene Castle | McLaughlin | © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon | Photo by Allison White

In his short time in the sun, Cannon had absorbed the inspiration of widely diverse artists, notably Henri Matisse, Vincent van Gogh, Gustav Klimt, and modernists such as Larry Rivers and Jasper Johns. Two Guns Ankara juxtaposes the pose of a formal 19th-century studio portrait with Fauvist color and Pop Art elements, including the subject’s purple pompadour. “It’s as if he was referencing visual languages he understood and loved, but he made them his own,” Kramer remarks. “He was not derivative at all.”

Cannon’s work also continually commented on the Native experience, past and present. At times, he used historical photographs as reference, as with Beef Issue at Fort Sill, based on an 1893 photo of women butchering a rationed steer at an Army outpost in Oklahoma. For Cannon, the image spoke of the strength of Native women, as well as the movement from oppression to resilience on the part of all Native peoples, Kramer says. And while the artist had no qualms about making political statements in his work, he was adept at incorporating wit, irony, and subtle tongue-in-cheek elements that delight the eye, rather than pushing viewers away.

A number of Cannon’s student peers at IAIA — who in many ways were mentors to each other and to Cannon — would go on to also become renowned artists, including Kevin Red Star (Crow), Linda Lomahaftewa (Hopi/Choctaw), Earl Biss (Crow), Bill Prokopiof (Aleut), Alfred Young Man (Cree), and Doug Hyde (Nez Perce). Over the years, many other acclaimed contemporary Native American painters have looked to Cannon with respect and admiration, notes Tatiana Lomahaftewa-Singer (Choctaw/Hopi), curator of collections at the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe. Among these are Darren Vigil Gray (Jicarilla Apache/Kiowa Apache), David Bradley (Minnesota Chippewa), and Tony Abeyta (Diné).

Yet, Cannon would not confine himself to the label of Native artist. “[I]t seems beside the point to call a painting Indian just because the artist is an Indian,” he once said. As Kramer points out, “One of Cannon’s greatest legacies is that his work commands such a presence that it goes beyond the borders of Native American art. Certainly he acknowledged his Native heritage, but he wanted to be understood as an artist writ large — he wanted to be understood as an American artist and a Native artist.”

No Comments