29 Oct When ‘Less Is More’ Goes Big

Joel Ostlind has a preternatural ability to tell a story in simple lines, without relying on color to fill in details like time of day or season. But how he transforms those drawings into elegant small-edition etchings, pulled by hand, as the earliest printmakers of the 16th century did, is the stuff of poetry.

Over the last four decades, Ostlind has become renowned for his intaglios, which portray nature, ranch scenes, wildlife, and two of his favorite pastimes: fly fishing and skiing. Though small in size — typical etchings range from 4 x 5 inches to 9 x 12 inches — his works on paper are the epitome of the paradox: less is more.

From miniature pen-and-ink to monumental installation, muralist Lisa Norman worked with Joel Ostlind to bring The Riding on the Wall to life, adding Western flare to the old F.W. Woolworth building in Sheridan, Wyoming. Photo: Joel Ostlind

“Whistler said every medium had an optimal size,” Ostlind says. “I believe the optimal size for an etching is small, so that each line becomes gem-like.”

To that end, Ostlind steadfastly avoids clutter — he is disciplined in brevity, which is why his etchings depicting the West read as meditations. The wisp of a cloud may be communicated in a handful of lines, and the rhythms of an angler casting a line or a ranch hand twisting a lariat recognizable by spare gestural marks.

Interestingly, however, after all these years and thousands of drawings and etchings, Ostlind hasn’t strayed from creating those miniature gems.

Fancy Flies | Watercolor | 5 x 7 inches

Enter businessman Paul DelRossi, who grew up in Massachusetts, attended Harvard, and then, while exploring the West, got caught in the tractor beam of Sheridan, Wyoming’s charm. Part of that charm is the town’s Main Street Plaza with its old buildings and wide streets. But the Woolworth store, which had been a hub in the small agrarian community, had closed when the chain shuttered in the late 1990s and sat vacant, leaving residents with a melancholic longing for days gone by. So, in 2023, when DelRossi and his business partners learned that the building was for sale, they jumped at the chance to restore its civic relevance.

The Riding on the Wall | Mural | 10 x 66 feet | Photo: Adam Jahiel

Working with the Downtown Sheridan Association, whose mission is to preserve, enhance, and promote Historic Downtown, DelRossi and his partners have encouraged small boutiques and locally owned businesses to move into the building. But while the interior was taking shape, the exterior desperately needed a facelift. “Our intent for the exterior was to use art to make a statement and let it be a way to revitalize the presence of a building that had been a fixture for generations of people,” DelRossi says. “We have a community where a deeper abiding sense of history matters.”

Morning on the Mighty Mo | Acrylic on Linen | 12 x 20 inches

DelRossi partnered with Security State Bank-Sheridan and convened a committee of citizens, Ostlind among them, tasked with finding a solution that was both contemproary and timeless for the Woolworth building. Ostlind suggested that the committee visualize the wall as a canvas. He asked them to imagine a mural — nothing too loud or imposing, no need for blasts of color like a billboard out along the interstate — just an open-ended visual narrative to invite quiet reflection.

Hmm, so, maybe he had considered his work writ large….

The Good Life | Etching | 4 x 6 inches

Ostlind’s journey to becoming a fine artist began as a real-deal, working-for-wages cowboy. Born in Casper, Wyoming, in 1954, his parents pushed their errant son into college where he could earn a degree and join the professional working world. He met Wendy at Casper College, and they married in 1978. The professional life, however, could wait. The newlyweds headed to the Texas Panhandle to live the romantic life of cattle hands on the L7 ranch. Over the next 14 years, they moved through ranch jobs, winding their way north to the legendary Padlock Ranch in Southeastern Montana. Ostlind’s day job was cowboying; Wendy’s was camp cook and fill-in on branding crews. But in the evenings at home, while Wendy read, Ostlind would pull out his sketch pad and draw.

In the Rope Corral | Etching with Aquatint | 3 x 8 inches

“The third cow camp we lived in on the Padlock,” he recalls, “was a gorgeous old ranch, the Bar V. When we were there, an art director and his photographer came to shoot the Marlboro Man cigarette ads.” Ostlind decided to show the director some of his drawings and watercolors. After looking through them, the director said, “Yeah, you could do this.” Ostlind says, “That was my first art critique that gave me validity and changed the course of my life.”

Infinite Wisdom | Etching | 5 x 10 inches

By now, the couple had a young daughter about to start school, so they moved closer to town. The cowboy life, too, was starting to take its toll. “You get banged up,” Ostlind says, “and the crews of new cowboys, they keep getting younger and younger.” He took a job near Eatons’ guest ranch, where he spent his mornings feeding cattle with a horse-drawn wagon and his afternoons in the local library, checking out art books to teach himself everything he could.

Hills Brothers | Acrylic on Linen Panel | 6 x 8 inches

When he felt he had a strong selection of drawings, he had a show at a local bank in Sheridan. His work sold quickly and soon people were calling asking for more, which is when he thought etchings might be a good way to have more work available. He took a printmaking class taught by Jim Lawson at Sheridan College and was instantly hooked on the process that beautifully translated his pen-and-ink drawings into small fine art editions.

Around this time, he and Wendy bought a log cabin near the Big Horn mountains, and he went to work building a studio. “Mornings were for building,” he says. “Afternoons were for printmaking.” When the studio was ready, he installed an Ettan press with a 40-inch-long bed.

The Blue Moccasins | Acrylic on Linen Panel | 7 x 10 inches

While his etchings are rooted in the Old World methods of Rembrandt’s time, flowing through Ostlind’s body of work are naturalistic motifs that Old Masters might not have understood. Such as how big open spaces are humbling and that unconquered wildness is never far away. Ostlind also painted in oil, but he developed an intolerance to the medium and shifted to acrylic, with which he says he has a love-hate relationship. “It has some incredible properties, but it’s difficult to use when I’m out plein air painting,” he says. “In arid Wyoming, once it dries, it’s permanent. Because of that, I’ve moved more into watercolor and gouache.”

Long-time friend and admirer of Ostlind’s work, Kenneth Schuster, retired director and curator for the Bradford Brinton Museum says, “As a cowboy and as an artist rooted in that tradition, Joel is the real deal. He’s not a pretender and isn’t flashy like those who believe they are playing a part in some Western film.” Ostlind’s subtle ability to distill the essence of what he sees, Schuster believes, is his secret power. “It’s because he can render lines so well; he just has that ability. If he were a more self-promoting artist, he could be one of the most renowned names in Western art. But he’s not going to chase fame and glory — he doesn’t have to.”

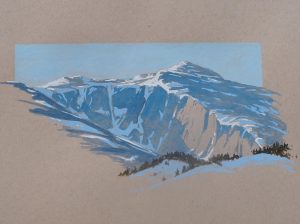

Winter Wall of Light | Watercolor and Gouache | 5.5 x 9.25 inches

Back in 1998, Ostlind had created a series of conte crayon drawings of horses and riders. One was used for a poster commemorating a rodeo in the town of Kaycee, Wyoming. After that meeting with DelRossi and his committee at the Woolworth building, Wendy reminded Ostlind of those drawings and suggested he show them to the committee, which he did. The response was immediate. DelRossi says, “Joel came back to us with a sketch that measured 4 x 22 inches. But it was way more than that. It had an impact exponentially bigger than its dimensions. It wasn’t hard to imagine how it would enliven the Woolworth wall.”

Ostlind, however, isn’t a mural artist. Thankfully, an old friend who also had worked on the Padlock Ranch was. By a wonderful twist of fate, Ostlind crossed paths with Lisa Norman at an exhibition in Cody, Wyoming. As he told her about the mural, Norman began to ask questions about how he planned to make it — Ostlind had no idea how to answer her. Not only had Norman become a sought-after muralist, but she also understood Ostlind’s work on an intuitive, shared experience level. He put her name in front of the Woolworth committee and soon the two ranch-hands-turned-artists were collaborating on a mural.

Painting with Relish | Acrylic on Linen Panel | 6 x 8 inches

They started the project in December 2024, in the basement of the Woolworth building. The mural consists of 13 10-foot-tall weatherproof aluminum-composite panels made of Dibond, gessoed, and painted in acrylic then sealed to withstand the elements. The 10-foot-tall by 66-foot-long mural, aptly titled The Riding on the Wall, was unveiled June 18, 2025, to much fanfare. Schuster enthusiastically says, “Riders on the Wall just may be the largest etching, in an edition of one, ever imprinted upon a public space in the West.”

“It was a stunning collaboration combining Joel’s art and Lisa’s interpretation; it is magnificent,” DelRossi says. Part of Ostlind’s concept was to depict the outlines of horses, cowboys, and Indigenous people in an impressionistic manner, with only the suggestion of tack. DelRossi invited his friend, the legendary horse whisperer Buck Brannaman, to see the mural, and asked Brannaman if he noticed anything missing. “Buck looked out of the corner of his eye and said, ‘Do you mean none of the horses have bridles?’” DelRossi recalls. “He told me that the thoughtfulness and presentation of the imagery was perfect, which is high praise coming from him.”

Behind the Cook House | Watercolor and Gouache | 6 x 9 inches

In the months since it debuted, the area around the mural has once again become a meeting place, with visitors routinely standing in front of it taking selfies. DelRossi says, “I see how people interact with it, and my response is, ‘Yeah, we nailed it.’ It’s just like the old downtown store used to be.”

Considered a Wyoming treasure himself, Ostlind has been honored over the years with solo shows of etchings and paintings, as well as a University of Wyoming show that traveled across the state not once but twice, hanging in museums and public libraries.

As for the mural and his experience of seeing his diminutive drawing made monumental, Ostlind says, “Many people are involved in a community project like this, from the first idea to completion. Working on the Woolworth Building mural strengthened my understanding of the term ‘public art.’” And he adds, “My mother was born on Lewis Street Hill, a few blocks from the mural. She died in 2017, but I wish she could see how art has given her old stomping grounds new life.”

No Comments