29 Dec The Giant in Our Midst

ACROSS AMERICA'S GREAT PLAINS, aboriginal stories tell of what happens when an old bison patriarch dies.

Sensing that a momentous loss has occurred within the herd, buffalo from miles away converge, forming a circle around the departed and, in homage, pay their respects before scattering again to the wind.

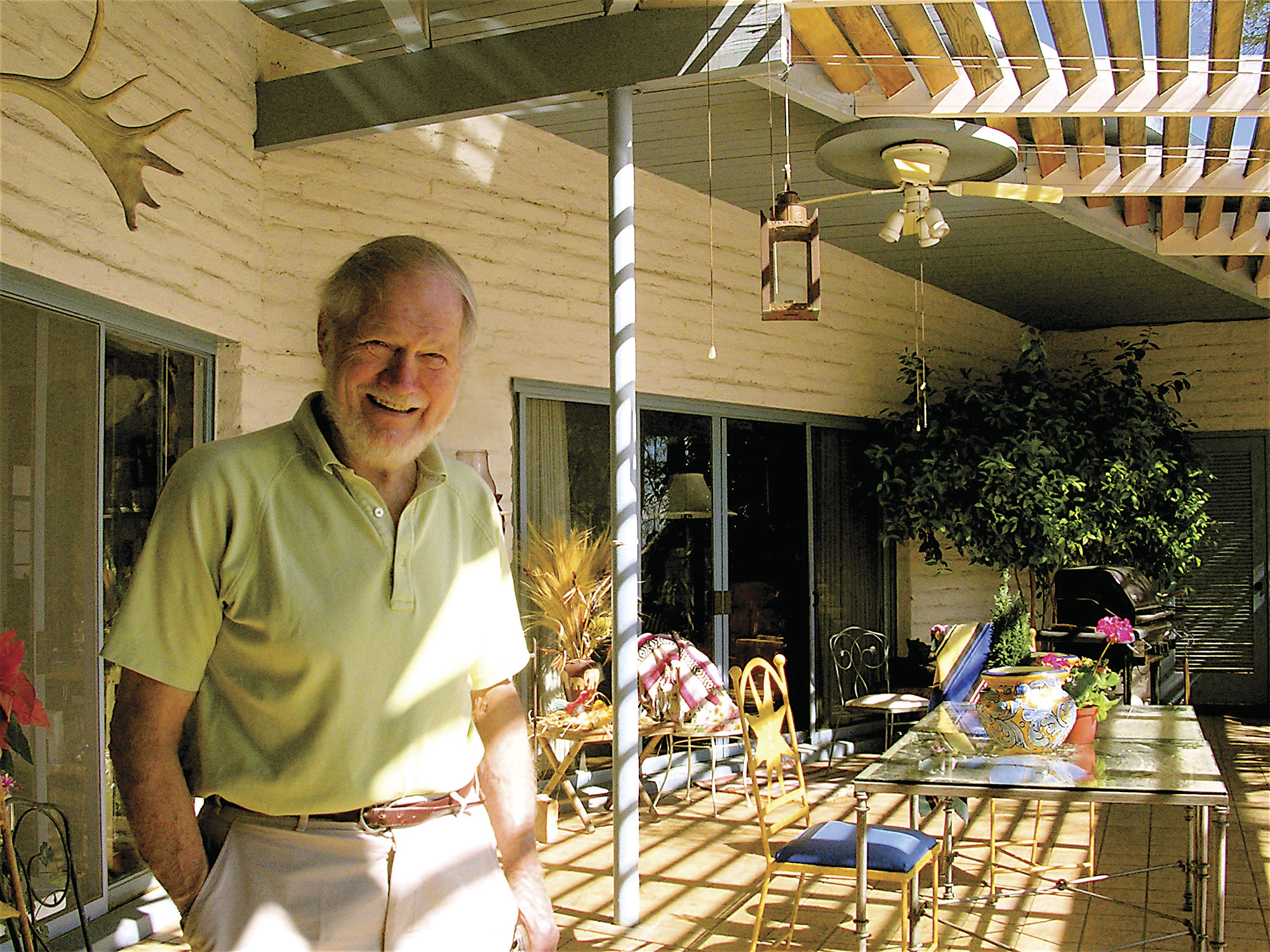

In early November, 2007, many of the finest artists in the country assembled in Tucson for a memorial honoring Robert Frederick Kuhn, who passed away on October 1st at age 87.

“It was a remarkable gathering. Considering the distances that people traveled to be there and the range of his friendships and acquaintances that went back to the first half of the 20th century, it was indicative of how much he was loved,” says Bill Kerr, Trustee Emeritus at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming.

For a genre like “wildlife art” so closely identified with the U.S. West yet extending to every corner of the globe, Bob Kuhn was widely hailed as the greatest living animal painter on the planet. It is worth noting that one of Kuhn’s last classic paintings, High Plains Lothario, portrayed a bison bull trudging toward the top of a lonesome prairie hill past a woolly admirer.

As an artist, Kuhn earned a swooning gravitas for his sensual interpretations of both North American and African big game species. In spite of a post-modern age that wields a notorious urban bias against animal subject matter, the impact of his original approach to Realism — propelled forward by a romantic reverence for nature — cannot, by anyone, be denied.

“It is inadequate to say his art was ‘special’ or ‘valuable’ or ‘the best of its time,’ ” Kerr says. “Bob Kuhn’s art was unique, and it still is unique, and it will remain so, no matter who follows behind. That alone is something exceedingly rare.”

Some artists paint bowls of fruit or vases with flowers. Others make human portraits their forte; still others are magnetized by pastoral scenes or cityscapes; and a few high priests of “conceptualism” put vacuum cleaners inside Plexiglas cases and proclaim themselves to be cosmic geniuses.

But as Kuhn’s own son, Casey, notes, the truth about his father is that he lived to observe wild creatures and the places they inhabited, but his intellect and unfailing desire to be contemporary made his subject matter almost immaterial.

Born in Buffalo, New York, in 1920, Kuhn was an artistic descendent of the “Golden Age of Illustration” — that time in American history when fine artists, classically trained in studio painting, earned their livings by providing visual illustration for books and magazines before the advent of television. Among the luminaries from the era were Winslow Homer, N.C. Wyeth, Howard Pyle, Harvey Dunn, Philip R. Goodwin and Maxfield Parrish.

Kuhn himself was a graduate of the Pratt Institute. He became a member of the so-called “Connecticut mafia,” esteemed illustrators who worked for major firms in New York. Early on, he was mentored by the famous magazine illustrator Paul Bransom, who later in his career spent 16 summers painting wildlife and landscapes in the Tetons. Bransom, best known for illustrating books by Rudyard Kipling and Jack London, had “a hypnotic effect” on Kuhn. He emphasized that there exists no substitute for drawing from life. His favorite venue: the zoo.

Kuhn did not regard drawing as a technical exercise undertaken simply to reflect animal anatomy; it was, instead, a vehicle for moving closer to the souls of his subjects. Following three decades in Connecticut grinding out images for a variety of clients, including sporting magazines and firearms manufacturers, Kuhn pursued painting full time and resettled with his wife, Libby, in Tucson, along with several friends who became major forces in Western art.

Today, the National Museum of Wildlife Art boasts a permanent collection that includes works by Karl Bodmer, George Catlin, John James Audubon, Frank Tenney Johnson, Thomas Moran, Albert Bierstadt, Charles Russell, Bruno Liljefors, Anna Hyatt Huntington, Maynard Dixon, Auguste Rodin, Rembrandt Bugatti, Paul Manship, Pablo Picasso, Georgia O’Keefe and Andy Warhol. A central core is a large corpus of works by legendary Carl Rungius — the largest public assemblage of original Rungiuses in the United States.

But museum curator Adam Harris notes that the vault also has some 90 original paintings by Kuhn, more than any other museum in the world. In addition, the NMWA has a motherlode of Kuhn’s landscape studies, drawings and sketches. “It is a good quantitative measure of how valuable Kuhn’s work is and how important he will be remembered in posterity,” Harris says.

A believer in challenging convention, Kuhn refused to apologize for his adoration of wildlife and yet he defied the pejorative stereotype so often affiliated with duck stamps, greeting cards and photo realism. Kuhn’s paintings are part of major private collections and in recent years they have fetched soaring prices at auction.

Painters Howard Terpning and Harley Brown, old friends of Kuhn’s in Tucson who also worked as illustrators, spoke and wept at his memorial. “You can’t talk about his art without talking about him,” Terpning says. Kuhn was hale and barrel chested and funny and generous to young artists, as Bransom had been to him. He was also formidably well read and serious and intolerant of BSers. He loved to fly-fish, travel, eat good food, listen to classical music, play tennis and cards and swim with grandkids in his backyard pool on hot days in the Sonoran Desert.

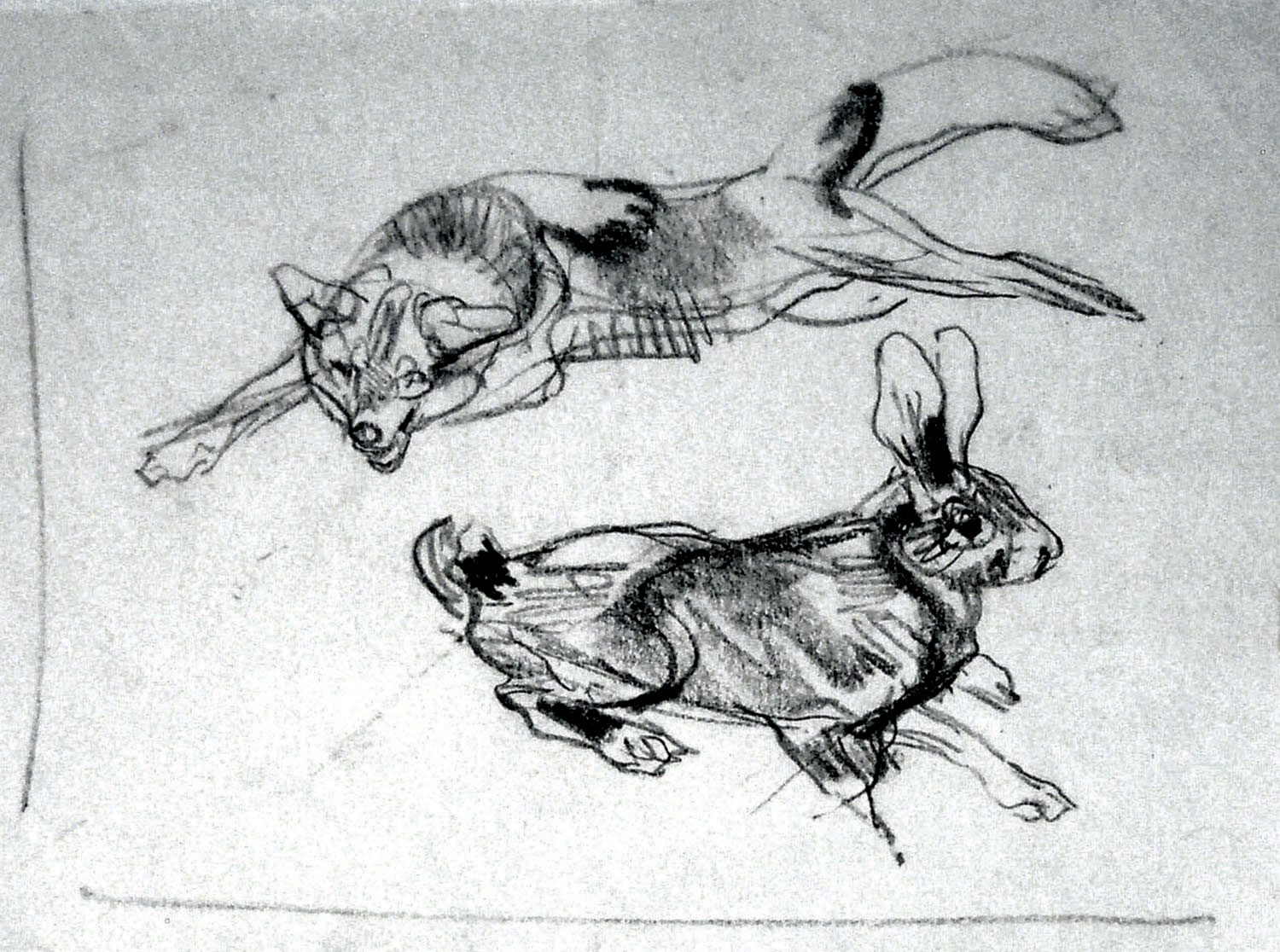

But most of all, he lived to draw. Incessantly. He composed thumbnail sketches on napkins that turned into epic paintings. “Kuhn was such a master of the quick study, or what he called ‘the gesture sketch,’ ” the National Wildlife Museum’s Harris says. “His drawings engage you because they provide insight into the mind of a brilliant artist. They are, on the one hand, so seemingly spare. But they perfectly communicate the architecture of what became grand Kuhn paintings.”

The way that Segovia stretched his fingers to warm up for a concert or Rachmaninoff cracked his digits for a marathon session on the ivories, Kuhn embraced drawing as an act of breathing.

“I have some of his drawings and have seen so many of them — we’re talking thousands — built upon decades of previous work,” Brown said. “When he looked at a wild elephant, for example, and examined in a sketch the way its back joined the neck and head, it was extraordinary. It was almost like seeing Brando give a performance in On The Waterfront. The thing is, he made drawing look so easy when it isn’t.”

Like Kuhn, Brown studied in the East. He attended the Art Student’s League. “You learn from the masters how to put down a line and then come in with a killer line. Bob would put in those simple killer lines that said everything. He did it with his drawing and with a few strokes of paint,” Brown said.

“It was all about economy of line, economy of brushstroke, paring down the power of expression to its purest essential,” adds Terpning. “The very simplicity is what gave it beauty, but coupled with his sense of color and design, and it turned into something magnificent.”

Once, when this writer visited Kuhn in Tucson and asked him to describe the things about wildlife painting that stirred his soul, he paused, then replied simply that he approached every blank surface — he painted in acrylic on board — as he believes a Latin troubadour would. When sketching compositions, he imagined himself as a musician improvising sonatas, imbuing them with melody and narrative that were his own interpretations. “I sometimes think of myself as singing ballads about these animals,” he said. “I’m not here to give you the dull facts. I’m trying to tell you why I love them.”

Adorning Kuhn’s studio walls, filling books on the shelf and filing cabinets, besides 70 years’ worth of drawing, were images of color studies and paintings created by two of his heroes, abstract expressionists Mark Rothko and Franz Kline. Like them, Kuhn had a visceral response to color and form. “I love abstraction but my mind doesn’t work so intensely as Rothko’s did,” Kuhn said in an interview. “I don’t have a color theory but I have my own ideas for how to utilize color.”

“Beyond his ability as an artist, he possessed a profound understanding of nuance, of gesture, of the essence of whatever he painted,” Kerr said. “Most wildlife artists paint the same Dall sheep every time, the same grizzly bear every time. Kuhn painted individuals. That’s one of the subtleties that, in my opinion, propelled him beyond even Rungius.”

Stuart Johnson, owner of Settler’s West Gallery, in Tucson, suggests that Rungius represents one end of the wildlife spectrum and Kuhn the other. “Rungius was interested in the classic pose, the regal Kodacolor moment,” he explains. “Kuhn would take animals and put them into situations no one would ever think of and that’s what made him a visionary.”

Sculptor Ken Bunn remembers trips to the African bush he took with Kuhn, when they would be in the middle of nowhere and a pride of lions would emerge and roar and prowl closer to investigate. “In 15 minutes or less, he would have this elaborate sketch of the encounter and it was magical,” Bunn says. “The kind of originality that he possessed does not come from having a limited perspective. It comes from having your eyes and mind open to everything that is going on around you. You try to make your work state something that you believe in.”

Animals were Kuhn’s vessel for expressing big artistic ideas and social commentary, but he chafed at the notion of painting pretty pictures. What made a Kuhn a Kuhn was his fondness for banded color tones, the dynamic flow of his subject matter and a delight with playing mischievousness against mortal danger. It placed him in the realm of being avant-garde.

A testament of Kuhn’s place in the pantheon of American art is this: Not long ago, Pratt, his alma mater (which has proudly incubated some of the most critically acclaimed minimalists, abstract expressionists and avant-garde post-modern urban artists of the last 50 years), named Kuhn one of its distinguished alumni.

Two of Kuhn’s masterworks are Pas de Deux (1975) and Flat Out (1985). Both are portrayals of predator and prey, with jackrabbits athletically outwitting respectively a fox and coyote. Kuhn, however, was not a gore-ist. He said blood was utterly unnecessary and tasteless.

“He would deliver you to a moment and take great pleasure in revealing the elements that were visible to him in his mind and subconscious,” Brown says. “But what happens in the next seconds is up to the gods.”

Kuhn was a keen thinker, fully capable of tangling with the fine-art cognoscenti. A few years ago, when a so-called critic with the Globe and Mail newspaper savaged an exhibition in Toronto staged to celebrate the works of Rungius, who emigrated to Canada from Germany, there was no one better positioned to mount an artful rebuttal.

The less-than-articulate writer called Rungius’ historic wildlife scenes “sentimental dreck” and claimed that viewers had to overcome their “gag reflex” when confronting scenes of large mammals.

Among the indicting broadsides fired at wildlife art was a condemnation of Rungius — and, by association, the entire genre — for gleaning information from the trophy animals he had shot. “Now, there is without question something deeply creepy about all this,” wrote Sarah Milroy. “The environmentalist wildlife artist loved nature so much that he had to … kill it so he could get a better look? Yes, that seems to be the idea.”

While Kuhn was generally gentle in his rhetorical pugilism with friends, he took off the gloves with her. He said that Milroy was naive to art history (the great painters and sculptors of the Renaissance sketched from human cadavers); she appeared to be clueless about the role Rungius played in aiding Canada’s conservation movement, which saved wildlands from industrial ruin and he said that apparently in her own urban depravity from natural beauty, Milroy was willing to overlook the lack of talent residing in many post-modern experimental artists who can’t draw and know nothing about paint. Milroy, Kuhn said, forgives urban human-on-human violence and blight while at the same time condemns sportsmen and nature lovers.

Rungius, Kuhn added, had in his own day silenced real critics when he left wildlife out of one of his landscape scenes, entered the scene in a juried competition at the prestigious National Academy of Design and was elected an academician, one of the highest fine-art honors.

In a written reply to Milroy, Kuhn noted that calling Rungius a bad artist because he painted wildlife and hunted some of his subjects would be tantamount for Ms. Milroy and her arbiters of good taste to dismiss Picasso’s portraits of women because the Spaniard was a vile man in his personal life who subjugated women to the role of sex objects and mistreated his models.

“Pop was a man who was about far more than his art,” Casey Kuhn says. “Growing up with him, I looked at him as just being my dad, but in later years, because of his longevity, I came to appreciate how brilliant he was. He was engaged in his world.”

Painter Randal Dutra, who studied under the late Robert Lougheed, in Santa Fe, sought critiques from Kuhn and was an Oscar-nominated animator for Hollywood blockbusters, says that Kuhn’s knowledge humbled his peers. He remained a standard bearer and his skill was a potent reminder of what is being lost among younger generations who suffer from nature deficit disorder and forsake draftsmanship because it is too difficult.

Drawing, Dutra says, is one of those fundamental things, like good grammar is to verbal fluency. When it is lacking, it is noticeable. When it is executed with brilliance, it becomes lyrical and ageless.

“Drawing is more about a way of thinking and organizing your thoughts,” Dutra says. “By going to zoos routinely and heading off to Africa or other wildernesses; and by studying something down to the last tendon, as Bob did, you free yourself to use your knowledge as an interpretive instrument while still respecting nature. When you acquire the confidence that he had, you are not afraid to change a gesture or improve upon the information that is being conveyed. You put yourself in a position to push the envelope. Bob Kuhn’s individual paintings are not a product of one experience but a library of experiences.”

“The act of drawing is a way of making something intimately your own. Long ago, when I was living in Botswana, I picked up a copy of Kuhn’s first book and I remember him calling his preoccupation with nature his ‘monomania,’ ” says Swedish-American wildlife sculptor Kent Ullberg. “Knowing him was like reaching out and touching one of the giants in art history.”

Remarkable is how seldom Kuhn ever repeated himself. While prolific and much in demand for private commissions, he resisted the temptation to rake in an easy financial windfall simply by knocking off virtual duplicates of his best-known works.

During his final months when he became taciturn knowing his heart was giving out, Libby would tell him to head into the studio and settle himself down by drawing or painting, friends say.

In the end, Kuhn stopped only when he had to. “The older you get the more you are humbled by nature,” Harley Brown says. “Like George Bernard Shaw once remarked: ‘It’s too bad that youth is wasted on the young.’ As we’ve grown old, we’ve all just started to get the big picture, to understand what it’s all about. Bob Kuhn always reminded us of the pure exhilaration you felt when you were making art. There is no one else like him who will walk this way again.”

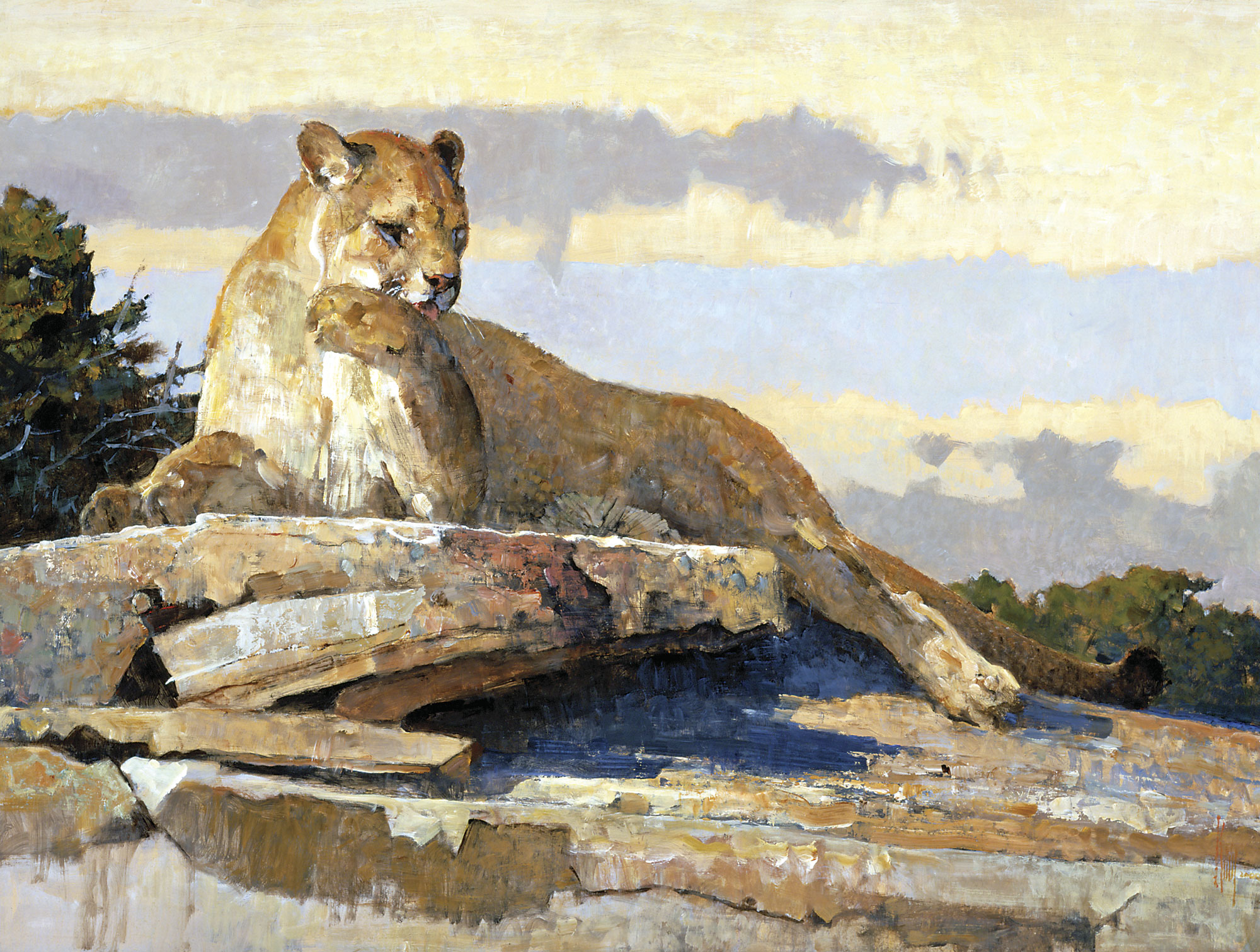

- “Flat Out”, 1985. | Acrylic on Masonite. | 14 3/8 x 18 3/8 inches. | National Museum of Wildlife Art.

- In the last years of his life, Kuhn the octogenarian still painted with a robust palette and a highly evolved sense of design. Nothing, it seems, could slow him down.

- “Poached Salmon”, 1974. | Acrylic on Masonite. | 24 x 40 inches. | National Museum of Wildlife Art.

- “Cruisin’” , 1980. | Acrylic on Masonite. | 22 x 48 inches. | National Museum of Wildlife Art.

- “High Plains Lothario” | Acrylic on Board | 28 x 34 inches | National Museum of Wildlife Art

- Sketch – Bear Heads, c. 1990. | Conte chalk on paper. | 14 x 11 inches. | Gift of the Artist; National Museum of Wildlife Art.

- Sketch – Coyote and Rabbit, n.d. | Charcoal on paper. | 5 x 6 ½ inches. | Gift of the Artist; National Museum of Wildlife Art.

No Comments