30 Dec Perspective: James Earle Fraser [1876-1953]

When visitors to the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco stood before James Earle Fraser’s End of the Trail, they would have experienced the towering sculpture as a reflection of certain beliefs about Native Americans and the Western frontier. But no single perspective represented those ideas within the American psyche.

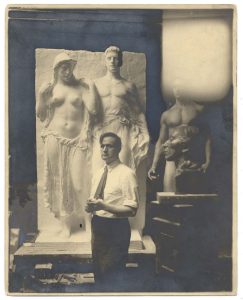

James Earle Fraser | Photographic Print | 9.84 x 8.27 inches | ca. 1919 | James Earle Fraser, ca. 1919. Miscellaneous Photographs Collection, circa 1845-1980. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

For some, the work’s title and its powerful visual impact — a monumental figure of a despondent-looking Indian on an equally weary horse — symbolized the necessary relocation of Native Peoples who stood in the way of Manifest Destiny, the westward movement of the American way of life. After all, this exposition, held at the western edge of the continent, was a tribute to new heights in the arts, architecture, engineering, and other forms of Euro-American progress in the young century.

Pan-American Exposition to Augustus Saint-Gaudens | Bronze | 3.563 inches | 1901 | Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederick S. Wait, 1909, 09.114a, Courtesy of The Met

For others viewing Fraser’s sculpture, the famous 1893 words of historian Frederick Jackson Turner no doubt came to mind. The frontier was closed, Turner had declared, and with that closure came the irretrievable loss for Americans of “a gate of escape from the bondage of the past; and [a loss of] freshness, and confidence … ” In this sense, End of the Trail conjured Euro-American nostalgia for the idea of unfettered freedom and opportunity through westward expansion. The belief that a noble race was on the verge of extinction enhanced this romanticized view.

Elihu Root | Bronze | 18.5 x 14.5 x 12.5 inches | 1926 | Gift of Carnegie Corporation, 1929, 29.95, Courtesy of The Met

Still others staring up at the figure of a slumping Indian, his spear pointing to the earth, would have felt sympathy for people deprived of land, culture, and ways of life that had existed for many centuries. An unnamed critic in 1920 wrote of the sculpture as an indictment of “the national stupidity that has greedily and cruelly destroyed a race of people possessing imagination, integrity, fidelity, and nobility.”

James Earle Fraser Sculpting a Native American Model | Photographic Print | 9.84 x 7.87 inches | ca. 1910 | Miscellaneous photographs collection, circa 1845-1980. | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Thomas Brent Smith, Director of the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art at the University of Oklahoma, believes that for the artist himself, the sculpture’s meaning was unequivocal. “For Fraser it was not a celebration of Manifest Destiny, but rather, a lament for what was happening to Native Peoples and their cultures.” And unlike many late-19th- and early-20th-century artists with a passing knowledge of the West, End of the Trail emerged from Fraser’s personal experiences with, and feelings about, this continent’s original inhabitants.

Fraser was born in Minnesota in 1876 and was four years old when the family began incrementally moving west for his father’s job as an engineer with the railroad, which was rapidly making its way toward the Pacific. For nine years, a time of Fraser’s most cherished boyhood memories, the family lived on a large ranch near Mitchell, South Dakota.

It was an idyllic childhood, as the artist recounted in autobiographical sketches quoted in August L. Freundlich’s 2001 biography, The Sculpture of James Earle Fraser. Fraser loved the prairie, the rivers, his ponies, and dogs. Groups of Native Americans would leave the nearby reservation and make encampments close to the ranch, and young James played with the Indian boys. They taught him to ride, make toys, and use a bow and arrow to shoot bullfrogs and prairie dogs.

Fraser slept under buffalo robes decorated with designs he later remembered as exquisite. “On one the sun was painted with its rays extending to the edges; on another the moon and stars, all in beautiful and appropriate colors and fine design. I have looked through museums in vain to find the equal of those paintings,” he wrote.

Hunters sometimes overwintered with the Native people and stopped at the Fraser household to visit, sharing stories of their time with Indians. As Fraser recalled: “On one occasion, a fine fuzzy bearded old hunter remarked, with much bitterness in his voice, ‘The injuns will all be driven into the Pacific Ocean.’ The thought so impressed me that I couldn’t forget it, in fact, it created a picture in my mind which eventually became ‘The End of the Trail.’ I liked the Indians and couldn’t understand why they were to be pushed into the Pacific.”

The genesis of Fraser’s sculpting career also took place in South Dakota. A neighbor called Hunchback would sit on his porch and carve in stone from a nearby quarry, and the boy often stopped on his way home from school to watch. Soon Fraser was collecting chunks of what he called chalk-stone, “soft as cheese when it was first taken out of the quarry, but hardened when it thoroughly dried.” He carved chickens, dogs, and other animals. Fraser’s father was often sketching and drafting as part of his work for the railroad, and creative activities were encouraged in the large, close-knit family.

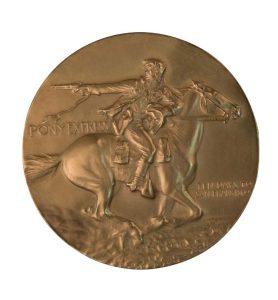

Pan-American Exposition to Augustus Saint-Gaudens | Bronze | 3.5625 inch diameter | 1901 | Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederick S. Wait, 1909, 09.114b, Courtesy of The Met

In 1889 the family moved back to Minnesota for the elder Fraser’s job. A year later they settled in Chicago, and as a young teen Fraser began taking classes at the School of the Art Institute. Importantly, he also obtained a position as an assistant in the studio of German-born sculptor Richard A. Bock, known for his collaborations with the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The experience gave Fraser what he described as “a wonderful opportunity for a boy to start actual work in a studio … even if it was only handing clay to the sculptor.”

Richard Bock was in Chicago preparing work for the upcoming 1893 Columbian Exposition, held in that city. Through him, and through the art and architecture presented at the exposition, Fraser was exposed to some of the finest American art of the day. In a letter, he wrote of “beautiful buildings and good sculpture on all sides. It was wonderful training for an art-minded youth.”

Sculptors including Alexander Phimister Proctor and Cyrus E. Dallin often portrayed Western subjects, inspiring young Fraser to begin making art based on his own experiences in the West. At age 17 he created the first model of End of the Trail.

He wanted to continue art studies, and in 1897 his father agreed — encouraged by a colleague’s positive response to the boy’s student art — to send him to Paris. There, at the École des Beaux-Arts, Fraser received rigorous training in traditional modeling techniques with live models. The Beaux-Arts approach was a fluid, naturalistic style with emphasis on light and textural effects, notes Thayer Tolles, Marica F. Vilcek Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. With Smith, Tolles co-curated The American West in Bronze: 1850-1925, an important exhibition that opened at the Met in 2012 and traveled to Denver and China.

While at the Beaux-Arts academy, Fraser had the good fortune of having his talent noticed by the Irish-born sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Saint-Gaudens was in Paris working on a monumental equestrian statue of Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman for New York City, and asked Fraser to assist him. Later Fraser served as an assistant in Saint-Gaudens’ Cornish, New Hampshire, studio.

An inspirational mentor and teacher, the elder artist left an enormous impact on a younger generation of American sculptors, Fraser among them. Not only did Saint-Gaudens impart technical skills that balanced Classicism and Realism, but equally important, he focused on American subjects, often from this country’s relatively recent past. As much as documentary, this type of sculpture served to honor those memories, with bronze as a medium for memorializing. Smith notes that Fraser’s work in bronze, along with the scale of his original End of the Trail, reflect the artist’s intent to memorialize.

Head of a Young Artist | Rosato di Milano Marble | 17 x 8.25 x 14.25 inches | 1933 | Rogers Fund, 1933, 33.93, Courtesy of The Met

Fraser enjoyed a long and prolific career, keeping a studio for many years in New York City, where he taught at the Art Students League between 1907 and 1914. Later he and his wife, Laura Gardin Fraser, a sculptor who had been one of his students at the Art Students League, lived and had studios on a farm outside Westport, Connecticut.

New Frontiers | Bronze | 2.875 inch diameter | 1952 | Gift of the Society of Medalists, 1953, 53.12.1, Courtesy of The Met

Much of Fraser’s work involved commissioned sculptural portraits of historic and political figures, among them a 65-foot-tall statue (including a 15-foot base) of George Washington for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. He also designed coins — the Buffalo Head nickel being the most well-known — and medals including the World War I Victory Medal and the Navy Cross. “He was remarkable for his range of scale,” Tolles says.

Yet if Fraser is known today for any single artwork, it is End of the Trail. At the 1915 exposition, the sculpture, cast in white plaster as monumental works were for such exhibitions, was immensely popular, regardless of how viewers interpreted it. The artist almost immediately began offering it in bronze in three sizes, often selling to an East Coast market hungry for portrayals of the West.

Following the exposition, the original End of the Trail stood for many years in Visalia, California. In 1968, its plaster deteriorating, the work was obtained and restored by the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, where it remains in the museum’s entryway. In the hundred-plus years since its San Francisco unveiling, the iconic image has been endlessly reproduced in countless forms, including paintings, prints, posters, t-shirts, bookends, bags, and belt buckles — even as album art for the Beach Boys’ 1971 record, “Surf’s Up.”

Yale University Memorial Prize to Henry Elias Howland | Bronze | 2.875 inches diameter | 20th Century | Gift of Charles P. Howland, 1917, 17.41.2, Courtesy of The Met

Likewise, meanings ascribed to it have shifted over time as American perceptions have changed. Contemporary viewers often see it as symbolic of Native American resilience, the opposite of the vanishing race trope, Smith says. Yet even today, there is no one single interpretation. Nuanced and metaphorically layered, the image’s ambiguity “allows it to be a mirror in which we reflect ourselves,” Smith says, adding, “Of all Fraser’s sculptures, none has the power of End of the Trail. It’s one of those visceral, universal images that carry throughout time.”

After 30 years of writing about artists and other creatives, Gussie Fauntleroy remains fascinated by the life experiences and soul that intertwine in an individual and emerge as art. She has written for national and regional magazines, newspapers, museums, and galleries, has served as a book and magazine editor, and is the author of four books on visual artists.

No Comments