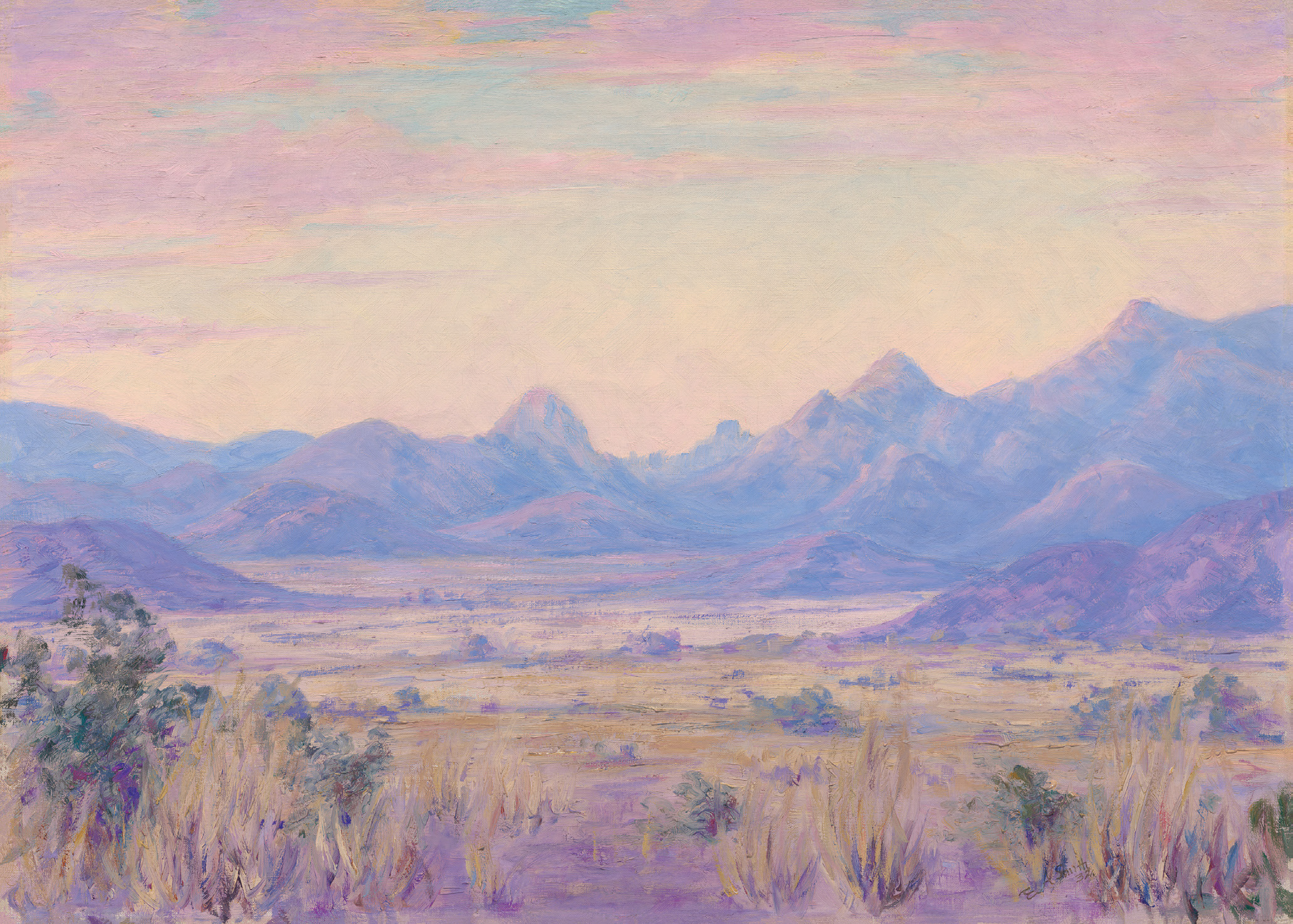

04 Sep Perspective: Effie Anderson Smith [1869–1955]

Effie Anderson Smith [1869–1955] had a theory about the lovely hues of atmospheric haze in the Arizona desert, a landscape she loved and painted for more than 50 years. She believed that microscopic particles of mineralized dust were suspended in the dry desert air, changing how the light reflects color there.

Beginning in the late 1890s, Smith painted these colors into desert and mountain scenes. The landscape, although arid, was more lush, more tinged with green than it would be a century later. Expansive vistas were unscathed by human activity. This was the pure natural world embedded in the artist’s soul, which she painted, almost daily, for most of her adult life.

Effie around the time of her 1895 wedding in Bisbee, Arizona Territory. | Collection of the Effie Anderson Smith Museum and Archive

“She revered the desert; she saw the beauty in it and really understood it on a very instinctual level,” says Dr. Tricia Loscher, Chief Curator and the Dita and John Daub Curator of Western Women’s Art at the Desert Caballeros Western Museum in Wickenburg, Arizona. Loscher co-curated the most comprehensive retrospective to date on Arizona’s first known female Impressionist landscape painter, Desert Paradise: The Art and Life of Effie Anderson Smith, which runs through February 15, 2026, with a formal opening planned for the evening of October 10, 2025.

Co-curated by Steven Carlson, president and curator of the digital Effie Anderson Smith Museum and Archive, the retrospective features almost 60 artworks spanning the artist’s career, from her earliest known painting, created at the age of 14, to pieces from the early 1950s — although she often did not date her paintings. Also on view are works by some of Smith’s painting students, photographs of the artist, and objects from her Arizona home, including monogrammed silverware, which originated as silver from a mine her husband managed, according to family lore.

A companion exhibition at Desert Caballeros Western Museum, Now You See Us: Celebrating the Early Western Women Artists Collection, places Smith’s work in the context of her contemporaries and other early Western female artists. In 2024, John and Dita Daub donated $1 million to the museum for the acquisition of works by Western women artists, with a focus on the period between 1900 and 1940. Now You See Us includes paintings by Jessie Benton Evans, Edith Hamlin (wife of Maynard Dixon), and Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton, among others, along with pottery, paintings, and textiles by Indigenous women of the Southwest.

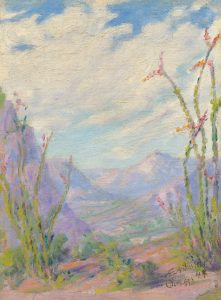

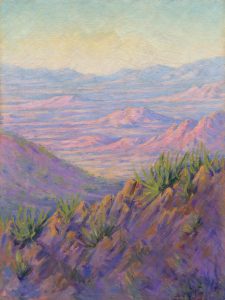

Ocotillos and Valley Scene | Oil on Canvas | 9.5 x 7 inches | 1944 | Collection of the Effie Anderson Smith Museum and Archive

Effie Anderson Smith was born in rural Arkansas in 1869 to parents who valued education and encouraged their daughter’s interests. Her father, Major Adolphus Anderson, was a farmer and civil engineer who relocated from South Carolina to Arkansas in the 1850s. Her mother, Martha Adelia, attended an all-girls academy with strong academics. Effie was sent to a similar institution — Hope Female Academy in Hope, Arkansas — to become a schoolteacher, which was one of the few careers available to women at the time.

Effie taught for two years, beginning at age 21, after her first husband died of tuberculosis three months into their marriage. Then, in 1894, following the death of her father and a massive tornado that destroyed most of Hope and the surrounding communities, Effie, her sister, and their mother moved to Deming, New Mexico, where Effie’s older brother lived. She accepted a teaching position and soon met Andrew Young Smith, who worked for the railroad.

When Andrew was transferred to Benson, Arizona, he and Smith married and moved to what would become her beloved, adopted home state. Andrew was soon offered a position as manager of a mine at Pearce, and in 1896 the couple settled in the mining camp.

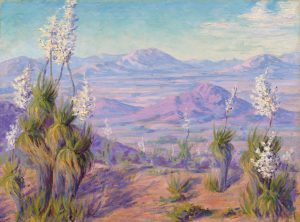

Desert Candles of Our Lord | Oil on Canvas | 18 x 24 inches | 1936 | Collection of the Effie Anderson Smith Museum and Archive

Smith fell in love with the desert. She established beautiful gardens at their home, likely using water pumped out of the nearby mine to keep the mine shafts dry, says Carlson, who has spent many years researching the artist’s life and gathering an archive of her papers and artwork.

Carlson’s great-aunt was married to the Smiths’ only surviving son, Lewis Anderson Smith, and Carlson grew up hearing stories about Effie. He is currently writing a biography of the artist, compiling a catalogue raisonné, and working toward establishing a physical museum for her art.

In Pearce, Smith painted as often as she could, although motherhood and social activities associated with being a mine manager’s wife occupied much of her time. The Smiths’ first son, Andrew, born in 1896, lived only four months. Lewis was born two years later, followed by Janet Annadel, who died at seven months. Painting became a mother’s refuge from these devastating losses, which Smith called “the great sorrow.” Loscher points out that Smith “had to have a lot of grit, determination, and strength of character, with the struggles she went through and how she persevered to continue her art. Those paintings are endowed with her spirit.”

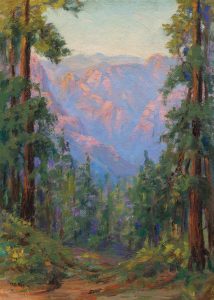

Cave Creek Canyon from Rustler Park – Chiricahua Mountains | Oil on Canvas | 14 x 10 inches | 1932 | Collection of the Effie Anderson Smith Museum and Archive

Over the years, Smith returned to the same locations many times to sketch, paint, and, in nearby mountains, find relief from the summer heat. The family and friends often picnicked in the Dragoon Mountains in a shady canyon called Cochise Stronghold. They also made the steep, daylong ascent by wagon or horseback into the Chiricahua Mountains, sometimes camping or staying in a cabin for weeks at a time.

After Smith’s husband died in 1931 and Lewis had moved away, her retreats to the mountains became less focused on socializing and more about absorbing and painting the landscape, Carlson says. Among his favorites is an untitled work referred to as Cochise Stronghold — Sunrise (Smith’s own title is unknown), featuring a violet and rosy-hued sunrise behind the Chiricahua Mountains. “It’s an especially effective use of color,” he says.

Although Smith had little formal art training growing up, her love of painting found expression early on. An untitled landscape made when she was 14 depicts an Arkansas river or lake dotted with sailboats and flanked by mountains. “You can already see her playing with the color palette,” Loscher says, describing the painting as “a gem.” From 1904 through the mid-19-teens, Smith traveled to the San Francisco area, Laguna Beach, and Pasadena to study with California Impressionists, including Anna Althea Hills and Jean Mannheim. Interestingly, she didn’t refer to herself as an Impressionist; she called herself simply a desert painter and colorist, Carlson explains.

Eventually, Smith’s teachers encouraged her to shift her focus from the coast to the desert landscape. While it is known that she did, almost all her art from before 1929 was lost that year in a blaze that started in an oil-fired water heater and completely destroyed the family’s home.

Sunlit Hills | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 18 inches | 1931 | Private Collection – Arizona

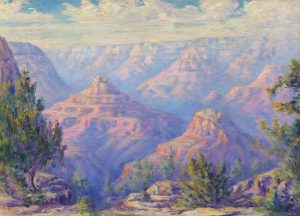

One painting pulled from the fire, View From the Head of Bright Angel Trail, contains two dates, 1928 and 1935, indicating that the artist reworked and finished it after the fire. The painting represents another of her favorite places: the Grand Canyon. “It has depth, great color, and is the working out of her technique,” Carlson says of the work. Between 1928 and 1948, Smith would produce more than 20 Grand Canyon paintings.

Although much of her adult life was spent in a small mining community, Smith’s connection with other artists and civically active women extended far beyond Pearce. For many years, she served as art chairwoman for the Southern District of the Arizona Federation of Women’s Clubs. She traveled and spoke at women’s clubs around the state and beyond. She taught landscape painting to young women. She motored her own automobile. She displayed and sold her art in galleries and exhibitions in California, the East Coast, at the Grand Canyon’s El Tovar Hotel, and in other hotels from Phoenix to El Paso.

View from the Head of Bright Angel Trail – Grand Canyon | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 28 inches | 1928-35 | Collection of the Effie Anderson Smith Museum and Archive

From 1941 to 1951, when not traveling or visiting her son in the copper-mining town of Morenci, Arizona, Smith lived at the Hotel Gadsden in Douglas, where she had a studio. Her years there were among her most prolific.

The economy was thriving after World War II, and the train made regular stops in Douglas, so she began producing smaller paintings to sell to travelers. Her color palette became richer, and her imagery shifted to desert flora. She created many paintings of yucca, a plant that embodied the desert’s dichotomies. “The plant itself is very strong, but there’s a softness and beauty in the flower,” Loscher observes. “In the same way, the desert can be very harsh, but it also sustains tiny creatures in a gentle way.”

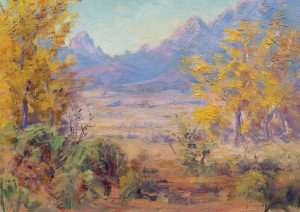

Autumn | Oil on Canvas | 10 x 14 inches | 1930 | Private Collection – Arizona

As Smith’s eyesight declined with age and she was less able to paint, she spent her last few years at the Arizona Pioneers’ Home in Prescott. Loscher sees it as a fitting final stop for an artist known as a pioneer, who “appreciated and revered the West. The desert gave much to her, and in turn, she shared what she’d been given.”

“Effie was a Southerner by birth, and everyone spoke of her as a lady,” adds Carlson, “but she was a Westerner by adoption and embraced the West. She wanted independence, and she also wanted the Southern model of family. She managed to have both at different times in her life.”

After 30 years of writing about artists and other creatives, Gussie Fauntleroy remains fascinated by the life experiences and soul that intertwine in an individual and emerge as art. She has written for national and regional magazines, newspapers, museums, and galleries, has served as a book and magazine editor, and is the author of four books on visual artists.

No Comments